Tahoe’s Water Diversion Schemes

by Mark McLaughlin

2006

Lake Tahoe is renowned around the world for its spectacular scenic splendor, but ever since a crude rock and log splash dam was constructed several miles below its outlet to boost river flow and facilitate log fluming, entrepreneurs have coveted the lake’s famously pristine waters. While the most outlandish schemes to appropriate Tahoe’s water were ultimately unsuccessful, today the magnificent alpine lake is primarily operated as a reservoir for irrigation storage and municipal water use in Nevada. Together with a handful of other public and privately owned reservoirs in the Truckee River system, Lake Tahoe provides about 75 percent of the water supply for the Reno-Sparks area.

The first outlet works on the Truckee River were constructed in 1870, but there were 19th century visionaries before then who dreamed of tapping and marketing Lake Tahoe as an unlimited, clean water source for both California and Nevada. It was a time when Americans were being dazzled by breakthrough advances in technology and engineering, an era known as the Age of Enterprise.

A Grand Plan

On August 18, 1864, the Lake Bigler Canal Company was formed with the grand idea of transporting Tahoe’s water over the Sierra Nevada to help expand the economy in Northern California. The company’s stated purpose was “to supply the people of Placer County with water for mining, irrigating, and manufacturing purposes by conducting and conveying the waters of the North Fork of the American River, its tributaries, and the water of Lake Bigler, onto the divides between the Middle and North Forks of the American River.” (From 1854 to 1945 Lake Tahoe was officially named Lake Bigler after California’s third governor.)

Old wooden Tahoe Dam in 1906 before construction of modern concrete slab and buttress design. Credit: Nevada Historical Society

The Lake Bigler Canal Company failed to implement its plan, but that was only one in a series of bold schemes to divert water from the Truckee River system. In the 1860s, a San Francisco-based engineer, Colonel Alexis Waldemar von Schmidt, acquired a half-section of land surrounding the Truckee River outlet and the right to appropriate 500 cubic feet per second of Tahoe water. It was a subtle and inauspicious beginning to what Von Schmidt was intent on engineering, a water project considered nothing less than the “Grandest Aqueduct in the World.”

The Prussian-born Von Schmidt exuded optimism, confidence, and a driving energy that enabled him to succeed at projects others considered impossible. He had arrived in San Francisco in 1849, but somehow resisted the impulse to join the gold rush. Trained as a civil engineer at American universities, Von Schmidt landed a job as a United States surveyor, mapping public lands and Spanish land grants throughout the state. Recognizing that “water flows uphill to money” and that a limited fresh water supply threatened to curtail the growth of San Francisco, Von Schmidt helped incorporate the Bensley Water Company. The company successfully built San Francisco’s first water supply system in the late 1850’s, but angry that the corporation did not pay him for the rights to use a water meter that he invented, he retaliated by joining the rival Spring Valley Water Company in 1860. Five years later, he had his revenge when Spring Valley bought out the Bensley outfit and established a profitable monopoly as the principal water purveyor to San Francisco.

But Von Schmidt had bigger goals than operating the Spring Valley Water Company. In 1863, he had submitted an ambitious plan to the Board of Aldermen in Virginia City, Nevada. Von Schmidt explained to the city’s leaders how Tahoe water could be piped over Spooner Summit down to Carson City, through the Washoe Basin, and then up to a reservoir on Mt. Davidson above the Comstock mines. Unfortunately for Von Schmidt, the aldermen doubted the feasibility of the elaborate and expensive pumping system needed to lift the water to the 6,000-foot elevation of Virginia City. (The idea of bypassing the Truckee River and siphoning off Lake Tahoe water directly refused to die quietly. As recently as 1952, the Bureau of Reclamation proposed tapping Tahoe water with a tunnel through the Carson Range with storage in Washoe Lake.)

An Even Bigger Plan

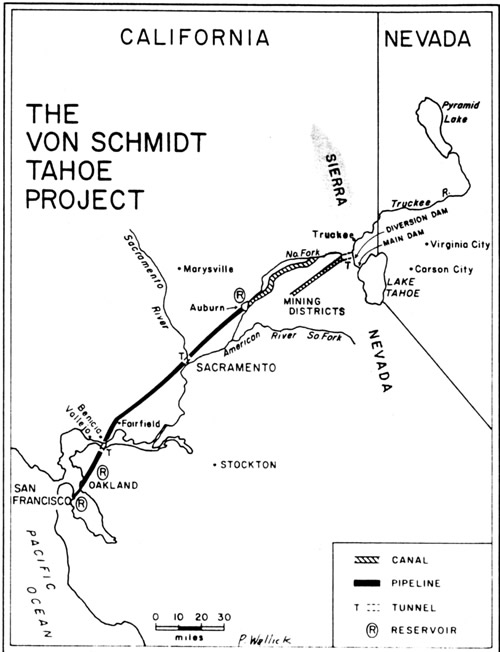

Map of Von Schmidt's elaborate plan to send Tahoe water to San Francisco

Credit: Donald J. Pisani, Lake Tahoe Research Group

Undeterred, the enterprising engineer hatched a new, more outlandish scheme. In 1865, Von Schmidt and five other investors established the Lake Tahoe and San Francisco Water Works Company to export the water of Lake Tahoe to the Bay Area, a distance of 163 miles. First among its articles of incorporation; “To take the waters of Lake Tahoe at or near its outlet, known as the Truckee River, and conducting the same through suitable canals, tunnels, flumes and pipes, to the City of San Francisco.” The plan required a diversion dam built about four miles downstream of the outlet, where a canal would branch off from the river and flow into Squaw Valley. A five-mile tunnel bored northwest through the mountains would carry the water to the American River watershed near Soda Springs. A complex system of pipes, tunnels, ditches, aqueducts, and reservoirs would transport the water to a storage facility at Hunter’s Point for use in San Francisco.

To fund the project Von Schmidt wanted the city to issue $10 million in bonds and he petitioned the U.S. Congress for a generous right-of-way package, which included large checkerboard land grants as well as any inherent timber and stone resources. Newspapers were initially exuberant at the prospect; the S.F. Daily Morning Call declared the project “decidedly the most stupendous water works enterprise ever undertaken on the American continent.”

Whose Water?

Nevada residents and politicians were hardly thrilled at the thought of a private company diverting and exporting water from the Truckee River to San Francisco. Wasting no time, Nevada Attorney General, George A. Nourse, challenged Von Schmidt to prove his legal entitlement to Tahoe water. He claimed that Nevada’s agriculture and mining industries were completely dependent on the Truckee River and held preeminent water rights through established usage. Von Schmidt assured Nourse that Nevada had nothing to fear; the six foot dam he planned to erect at the Lake Tahoe outlet would store enough water to supply both states. He also argued that California had a superior water claim to Tahoe because two-thirds of the lake and its outlet were within its border. In response, editor Joe Goodman of Virginia City’s Territorial Enterprise advised Von Schmidt to “bring to the mountains an escort of twenty regiments of militia” should the water diversion proposal succeed. “They will need them all,” Goodman warned, “for we will not submit to the proposed robbery.”

Despite the heated political rhetoric and the growing threat of a water-war between California and Nevada, Von Schmidt’s survey work continued. During the summer of 1870, his company built a stone and timber crib dam at the outlet of Lake Tahoe. Because there was little support for the water diversion project in Truckee, an armed guard was posted “to protect the dam against hot-headed residents.” Truckee’s factories and lumber mills used the river’s current to power machinery, and to float logs down the Truckee River Canyon. As it was there was only enough water volume to float logs for about four months of the year. Without the cheap transportation of Sierra timber, northern Nevada and Truckee would both suffer economically. An editorial in the Truckee Republican warned, “Violence would be used to prevent work on the project.”

Grand Plan Killed

When Von Schmidt’s proposal was submitted to legislators in Sacramento and Washington, D.C., it ran into strong resistance. Opponents argued that the federal government had no business subsidizing private corporations by giving away public lands. (Similar arguments were made regarding the generous government contracts issued for the construction of the first transcontinental railroad across northern California and Nevada.) Citizen groups and newspaper editorials complained that, like other projects under consideration that year, the proposed aqueduct reeked of corruption, so state and federal legislators killed the legislation.

Alexis von Schmidt’s “Grand Aqueduct” was never built, but several decades later the Bureau of Reclamation assumed control and rebuilt the dam to supply water for farming in the Nevada desert, and the Tahoe Water War Von Schmidt had ignited reared its head again. Controversy and litigation over the management of Lake Tahoe water appropriations continue to the present day.

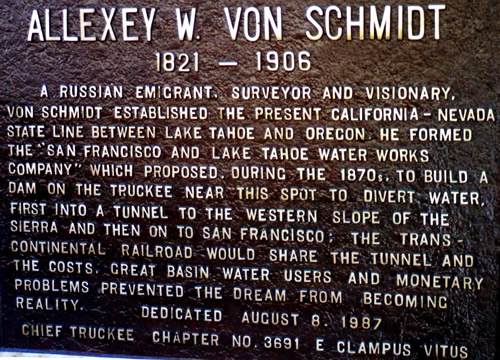

Colonel Von Schmidt historic plaque at Lake Tahoe Dam

Photo Credits

— Alexey von Schmidt, portrait: Portrait found in Francois D. Uzes, Chaining the Land: A History of Surveying in California. Sacramento, Landmark Enterprises, 1977.

—

The Von Schmidt Tahoe Project, Map, Pisani: Map from Donald J. Pisani, “Why Shouldn’t California Have the Grandest Aqueduct in the World?”: Alexis Von Schmidt’s Lake Tahoe Scheme; California Historical Quarterly , Vol. 53, No. 4 (Winter, 1974) , pp. 347-360, available on JSTOR at http://www.jstor.org/stable/25157527