Tamsen Donner: Dream to Legacy

by Mark McLaughlin

2006

Tamsen Donner lost her life in the harsh Sierra winter of 1846-47. She had been a dynamic schoolteacher and the wife of George Donner, the principle organizer of a California-bound wagon train from Springfield, Illinois. Poor decisions and a lack of leadership, bad advice and an early winter trapped the Donner-led group before they could cross the Sierra and reach the safety of California. More than once during that brutal winter Tamsen refused an opportunity to escape with rescue parties, but instead choose to stay behind with her husband George, who was seriously ill and could not travel.

Tamsen Donner lost her life in the harsh Sierra winter of 1846-47. She had been a dynamic schoolteacher and the wife of George Donner, the principle organizer of a California-bound wagon train from Springfield, Illinois. Poor decisions and a lack of leadership, bad advice and an early winter trapped the Donner-led group before they could cross the Sierra and reach the safety of California. More than once during that brutal winter Tamsen refused an opportunity to escape with rescue parties, but instead choose to stay behind with her husband George, who was seriously ill and could not travel.

Frances Donner —

No portraits of Tamsen Donner

are known to exist, but Tamsen's daughter Frances

(pictured here) strongly resembled her mother.

Credit: Photo courtesy of Ann Smith, Tamsen Donner's great-granddaughter

Too many versions of the Donner Party tragedy have been published over the years for it to be repeated here, but by reading Tamsen’s personal letters, one may gain some insight into the life and legacy of this historic heroine.

Beginnings

Tamsen Eustis was born into a respected, wealthy family in Newburyport, Mass., November 1, 1801. She enjoyed a happy childhood and her love of books was evidence of a curious mind and foreshadowed a lifelong commitment to education. After graduating with her teacher’s certification, she took a job at a school in Maine. Later she was offered a position as an instructor in an academy in Elizabeth City, North Carolina. Tamsen was not making enough money to survive economically in Maine, so she decided to take the job.

Though it meant a major upheaval in her life, Tamsen had no doubts about her decision. In a letter to her sister Elizabeth, dated 1824, Tamsen wrote “There is one impression, however, which rises above this huge chaos and presses itself upon my notice [to leave]. It is that the hand of God is remarkably visible in directing my steps. So fully aware am I that he will guide me, that I feel not the least hesitation in proceeding.” Tamsen said goodbye to her family and steamed south along the coast to North Carolina.

By 1829 she was 28 years old and still single, at a time when virtually all women were married by age 20. But Tamsen Eustis was no spinster; she was a committed professional. Teaching children was as important as marriage to this well educated, articulate young woman. That year, in Camden County, N.C., she met and married Tully Dozier. Apparently, Tamsen had found the right man. In one letter she wrote, “I do not intend to boast of my husband, but I find him one of the best of men – affectionate, industrious and possessed of an upright heart, these are requisite to make life pass on smoothly." Within two years they were the proud parents of a fine baby boy. Tamsen’s teaching salary combined with Tully’s farming income earned them a comfortable living.

Health Threats

Life for Tamsen seemed pleasant enough, but frequent winter fevers and widespread epidemics constantly threatened her family’s health. She mentioned that her little boy “has been very sick, and for a few days we feared we should lose him but at this time he is in fine health and sitting upon the table as I write. He at one time scolds me for the inkstand and at another knocks my knuckles with a spoon. He bears no resemblance to our family, being a true copy of his father.” Tamsen worried about her husband too: “I have had excellent health since I saw you, but Mr. Dozier has twice been reduced very low since we were married. His precarious health and our strong dislike to slavery has caused us to determine upon removing to some western state. But not until next year.”

The lure of the lush southern countryside had Tamsen and Tully fast within its grasp. But tragedy intruded, changing Tamsen’s bucolic life forever. A June 28, 1831 letter from Tamsen explained the situation all too clearly: “My sister I send you these pieces of letters that you may know that I often wrote to you even if I did not send. I have lost that little boy that I loved so well. He died on the 28th of September. I have lost my husband who made so large a share of my happiness. He died the 24th of December. I prematurely had a daughter, which died on the 18th of November. I have broken up housekeeping and intend to commence school in February. O, my sister, weep with me if you have tears to spare.”

Tamsen’s letters home went unanswered. When she finally received a response from Elizabeth, it was disappointingly brief. In July 1833 she replied “I received the scrap you sent me and read it over again to see if I could not make more of it; but twenty lines it was and with all my ingenuity I could not make myself believe that it was a well filled sheet. But sister, I will do as you like to be done by. See how close my lines are together, how small my hand, and how many words I put in one line; and say does it not please you? And will you not smile to see my name at the last end of the third page? Well, so should I like to have you write – so pleased should I be, and so would I smile at seeing no blank space in your letter. You cannot realize the delight I feel at the very sight of “Mrs. Tamsen Dozier” with a Newburyport postmark. And may you never know, for to feel it must be purchased at too dear a rate.”

Solace in Religion and Writing

Tamsen found solace in her strong religious faith. Despite personal tragedy and loneliness, she was able to write: “Tis morning and nature is lovely indeed. I rise very early and I cannot describe my feelings on viewing the dewy southern landscape. It seems as if my feelings struggle for vent and rushing to my pen are lost for want of words in which to clothe them. Why was I made with eye and heart to enjoy all these delights? To overcome all unamiable feelings – to participate in the joys and sufferings of others, to trace every incident in life to a Supreme power and realize that it is also the expression of goodness.”

Tamsen Eustis Dozier’s life in North Carolina was just about over. Her brother in Springfield, Ill., had asked her to come and take care of his motherless children. (Mortality rates in the 19th century were staggering.) His plea for help plucked Tamsen from her school in the South and pulled her out West, where she would meet George Donner, a wealthy farmer and her next husband.

The diminutive schoolteacher was an incredible bundle of energy, “scarce five feet tall and less than one hundred pounds.” One of her friends described Tamozine (Tamsen) Donner as the “perfect type of eastern lady, kind, sociable and exemplary, ever ready to assist neighbors and even strangers in distress.”

Seafarers Origin

Born and raised by a wealthy seafaring family on the coast of Massachusetts, Tamsen had steamed south to North Carolina for a promising school-teaching position. There she fell in love with Tully Dozier and the pastoral beauty of the soft Southern landscape. She continued to teach after their marriage, but Tamsen’s dedication to the health and welfare of her husband and young son never wavered.

Unfortunately, her happiness in the Southland was destined to be short-lived. Despite all she could do, her young family died during an influenza epidemic in the last few months of 1831. Without her loving husband and adored children, the magic was gone. Tamsen continued as a schoolteacher and remained active in the community, but was unable to shake her melancholy.

By the summer of 1832, however, Tamsen’s indomitable spirit had rejuvenated her positive outlook on life. She was content teaching schoolchildren in North Carolina, but a life in the sultry South was not to be her destiny. While on a visit home to Massachusetts, an urgent plea arrived from her recently widowed brother in Illinois to come and help him raise his children. His call for help plucked Tamsen from the piedmont of North Carolina and pulled her West, where she again found work as a schoolteacher.

Future Husband

In Illinois, while teaching botany to her pupils, Tamsen met George Donner, a wealthy landowner, twice widowed. George was described as a “big man, fully six feet tall, with black hair shot with silver. He was of cheerful disposition and easy temperament. Neighbors came to him for advice and sympathy.” On May 24, 1839, Tamsen and George were married. George had had many children by his first two wives, and over the next six years Tamsen gave birth to three girls, Frances, Georgia, and Eliza.

Tamsen loved her new life in Sangamon County, Illinois. George owned two large and profitable farms. The Donners lived on the smaller one, which comprised 80 acres of prime farm and grazing land, as well as extensive orchards planted with apple, peach and pear trees. They lived in a large five-room, two-story house. Their life was very comfortable. In a letter home, Tamsen wrote her sister: “I find my husband a kind friend, who does all in his power to promote my happiness and I have as fair a prospect for a pleasant old age as anyone.”

But Tamsen’s contentment did not diminish George’s desire for economic opportunity. Despite George’s advanced age of 62 years and his professions of satisfaction with the warm comfort of their beautiful home and farm, the spring of 1846 found the Donner family on the overland trail to California. George’s younger brother Jacob and his wife and family joined them in the bold move West.

Heading West

Tamsen wrote from the boisterous frontier town of Independence, Missouri, a favorite “jumping-off” point for West-bound emigrants: “My dear sister, I commenced writing to you some months ago but the letter was laid aside to be finished the next day and was never touched. My three daughters are round me, one at my side trying to sew, Georgianna fixing herself up in an old India rubber cap and Eliza knocking on my paper and asking me ever so many questions.” (George’s older children from his first marriage had refused to leave the luxurious lifestyles they were accustomed to; only two young girls from George’s second marriage, 13-year-old Elitha and 11-year-old Leanna were brought along). “I can give you no idea of this place at this time. It is supposed there will be 7000 wagons starting from this place this season. We go to California, to the bay of Francisco. It is a four months trip. We have three wagons furnished with food and clothing etc. drawn by three yoke of oxen each. I am willing to go and have no doubt it will be an advantage to our children and to us.” Tamsen intended to open a school in California for her children and others.

Tamsen Donner’s last letter was written near the Platte River and sent back to the Sangamo Journal, Springfield’s local newspaper: “We are now on the Platte, 200 miles from Fort Laramie. Our journey so far, has been pleasant. Wood is now very scarce, but “Buffalo chips” are excellent – they kindle quick and retain heat surprisingly. We had this evening Buffalo steaks broiled upon them that had the same flavor they would have had on hickory coals.”

Alder Creek Valley looking east towards snow covered Mt. Rose

Slowing Down

Their journey had gone well up to that point, but that would soon change. Their heavily-laden wagons slowed the oxen’s pace, which forced them to risk an untried shortcut that ultimately tested their strength and broke the group’s cohesive spirit. The struggling emigrants reached Truckee’s Lake (Donner Lake) around Halloween 1846, but there were already several feet of snow on the summit. George Donner had injured his hand repairing a wagon six miles north of Truckee’s Lake at a place called Alder Creek. After his hand was bandaged, George refused to go on, saying that he was too tired and worn out. He assumed that rescuers from Sutter’s Fort in California would soon come and assist them in the final leg of their journey over the Sierra Nevada. Despite his boundless determination, George’s age was sneaking up on him.

Sierra snowstorms came hard and fast that winter, trapping them without sufficient supplies. The two Donner families spent the winter at Alder Creek without cabins or sufficient food and supplies. Ultimately, several relief parties came to help, but the first one did not arrive until February 19, 1847, about three and a half months after they became snowbound. Tamsen repeatedly turned down the option to be rescued because she refused to leave her husband George who was dying from infection and starvation and could not travel.

The Children Carry On

The Donner Party’s epic story of starvation, cannibalism, and survival has been well-documented, but through the shadows of this dreadful tragedy gleams what must not be overlooked, the ultimate success of this personal family venture.

George and Tamsen Donner died in the deep Sierra snow, but they succeeded in getting all of their children into California. Those five girls, Elitha, Leanna, Frances, Georgia, and Eliza, gave birth to seventeen children among them. The Donner family paid a heavy price, but the survivors endowed California with an enduring legacy of pioneer determination.

In 1972, the eloquent New England poet Ruth Whitman articulated the Donner’s pioneer achievement with these imagined words by Tamsen:

“If my boundary stops here, I have daughters to draw new maps on the world they will draw the lines of my face, they will draw with my gestures my voice they will speak my words thinking they have invented them.

They will invent them, they will invent me, I will be planted again and again, I will wake in the eyes of their children’s children they will speak my words.”

Sun setting over Donner Lake and

Donner Peak, California.

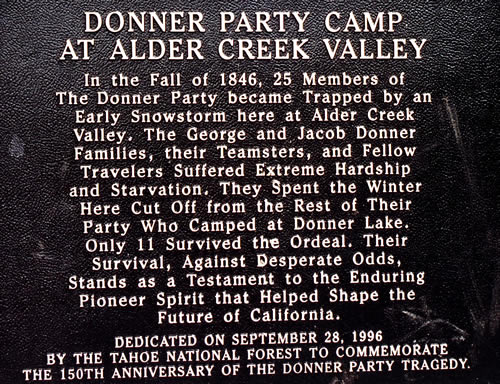

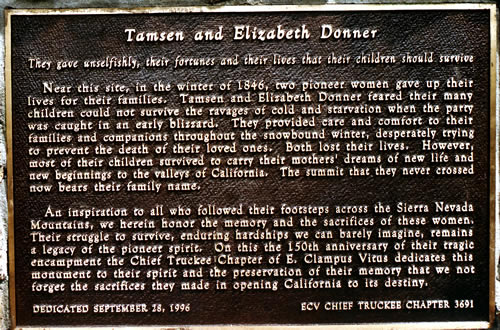

Historical plaques at Alder Creek site.

The author thanks Ann Smith, Tamsen Donner’s great-granddaughter for the use of these unpublished letters.

Photos not credited were taken by Mark McLaughlin