From A Winter in California

Mary H. Wills

Norristown, Pennsylvania: M.R. Wills, 1889

Mary H. Wills left Norristown, Pennsylvania, to spend the winter of 1888-1889 in Southern California. A Winter in California (1889) describes the highlights of her stay including visits to Pasadena, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Riverside, San Diego, Ojai Valley, Monterey, and Yosemite Valley. In the book, Wills shows special interest in climate, mission churches, shops, Chinatowns, hotels and restaurants.

In this selection, Mary Wills describes her winter visit to Yosemite Valley—a visit she describes in one word—“sublime.”

Yosemite Valley

The Journey Thereto—Something About This Great Wonder—Personal Mention—The Mariposa Big Trees.

The Journey Thereto—Something About This Great Wonder—Personal Mention—The Mariposa Big Trees.

To make successfully the tour of the Yosemite Valley requires nerve, strength and endurance. The way is long, precipitous and stony, but the reward is great. Artists may depict upon canvas, the camera reproduce with faithful minuteness, and the poet describe in words that burn—all efforts fall short in conveying any adequate idea of the grandeur of this greatest wonder of the Creator's hand.

There stand the mighty pillars of stone as they have stood for ages. There fall the majestic cataracts which have surged and beat since the world began, and poor, finite humanity can only come to the brink and gaze with humid eyes at the overpowering scene. I care not whether it sprung into being in one day, or that a thousand years were reckoned as yesterday in the sight of the Creator, it is the most awe-inspiring exhibition of Nature's works the world can produce.

Yosemite Means Grizzly Bear

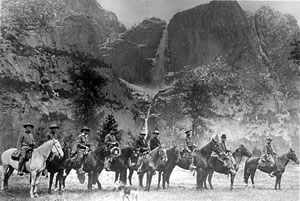

The name Yosemite signifies a great or grizzly bear. Previous to 1851 the valley was the abode of Indians. At that date there were two horseback trails leading to it, and a band of United States troops, to avenge some real or fancied wrong, descended upon the inhabitants and took possession.  Dr. Bunnell, who accompanied the expedition, thus writes: “None but those who have visited this most wonderful valley can even imagine the feelings with which I looked upon the view there presented. The grandeur of the scene was but softened by the haze that hung over the valley—light as gossamer—and by the clouds which partially dimmed the higher cliffs and mountains. The obscurity of vision but increased the awe with which I beheld it, and as I looked a peculiarly exalted sensation seemed to fill my whole being, and I found my eyes in tears of emotion.”

Dr. Bunnell, who accompanied the expedition, thus writes: “None but those who have visited this most wonderful valley can even imagine the feelings with which I looked upon the view there presented. The grandeur of the scene was but softened by the haze that hung over the valley—light as gossamer—and by the clouds which partially dimmed the higher cliffs and mountains. The obscurity of vision but increased the awe with which I beheld it, and as I looked a peculiarly exalted sensation seemed to fill my whole being, and I found my eyes in tears of emotion.”

The valley proper is about eight miles long and one mile wide. It is encircled by a perpendicular wall in some places nine thousand feet above the level of the sea. Prof. J. D. Whitney advances the theory that the bottom of the valley sunk down to an unknown depth owing to its support being withdrawn from beneath. The greatest scientists of modern times have visited and explored the region, and all are lost in wonder at its might, and can only conjecture regarding its age and formation. The soil is of a light gravelly nature, unproductive in its character and easily affected by the weather. An effort has been made during the past few years to introduce fruit trees, but with indifferent success. The forest trees, which are abundant but not of uncommon size, are mostly black and live-oak, a variety of arbor vitæ, maple, dogwood, willow, tamarack, and Douglass spruce. This last is what is otherwise known as Oregon pine, and is the most valuable lumber which can be obtained for building purposes, being almost impervious to water, not affected by climate, and universally used for piles, flumes and trenches.

Seven Day Journey

The journey proper of the valley is embraced in seven days. No heavy baggage is allowed, but good stout shoes and warm clothing are a necessity. By leaving San Francisco in the evening you reach Raymond in the early dawn, and are ready for the ride of sixty miles, two days in duration. At first the way is comparatively pleasant. There are said to be three hundred varieties of flower, shrub and tree in that first day's journey. There are entire fields of lupins, poppies, and the most delicate blue and golden tints. The sun's rays are sufficiently warm but not oppressive. The road is at times rocky, but never of the perilous nature we had heard described. It is steep and rough, the horses feel the loads they draw, but with a fresh relay every six miles you feel that their task is not burdensome; still, while it destroys the romantic aspect, it will be a humanitarian who introduces the iron steed. I do not say this is not a dangerous journey. Accidents do occur, but with stout, sure-footed horses, strong harness, and careful drivers, the risks are not very great. Your sense of enjoyment is so great that all feeling of personal discomfort is forgotten. It is the only scene which far exceeds all expectations. You pass through miles of magnificent specimens of pine trees, many of them measuring fifty feet in circumference, and being one hundred and fifty feet high. These are not occasional instances I am citing. We saw during the journey thousands of that size, well preserved, healthy, and as straight as an arrow. In some localities immense boulders are piled up, then you cross a rippling stream, and anon the mountain torrent dashes down hundreds of feet. There was a sprinkling of snow on the ground, the rain which overtook us in the valley shedding a mantle of white over the peaks and fringing the boughs of the pines with a robe of ermine. The ground is free from underbrush. There is naught to offend the eye, and a sweet, fragrant, woody smell greets the senses. I want my readers to feel that I am giving them no fancy sketch, or depicting things in a roseate light. I am trying to show a plain statement of facts.

Good Weather

The weather this season was exceptional, the roads being open at least a month earlier than usual, and the valley remarkably free from snow. Our greatest foe was mud, and the speed with which we at times descended the mountain was such as to make preservation our first duty, scenery and comfort being for the time ignored.

At noon of the second day you reach Inspiration Point, and the valley in its grandeur lies before you. There stands El Capitan, hoary with the frost of time, the noblest of them all, the undisputed chief among giants, from his cloud-topped head looking down seven thousand feet. You hear the rush of waters, and see the soft-falling, swaying foam, which bounds and meanders a thousand feet in the air before it strikes the rocks and forms the Bridal Veil.

The Three Brothers gaze in defiant might, and North Dome looks its almost sculptured beauty, while Clouds' Rest, true to its name and purpose, completes the picture. Meandering peacefully along, as though not cognizant of its place in the book of the world's wonders, flows the Merced river, in its bosom reflecting the majesty of its surroundings.

It is a moment when your strongest and deepest emotions are stirred. It is sublime. Far from the world and men, here, annually, in storm and sunshine, Nature repeats the wondrous tale, and unmoved by the elements, the same yesterday, to-day and forever, is sung the story of the might of the Creator. It has been my lot to wander in many lands, and see the glorious places which men call wonderful; never have I looked upon a sight so inspiring, so majestic, so perfectly incomparable, as the first view of Yosemite.

Descent to the Valley Floor

The descent to the floor of the valley is easy and rapid. For three days we sat at Nature's shrine and learned anew the lesson of her greatness. There are several trails. We chose the one to Glacier Point, eight thousand feet above sea level, and that one experience will suffice. Let no one be discouraged or deterred by reports of dangers to be feared. Every precaution consistent with safety is taken.  The road is precipitous, but it is three and sometimes four feet wide, with angles and turns of surprising sharpness, but generally protected by stones, logs or masonry, and in many places made less fearful by a thick growth of under-brush. The horse on which I rode—I use the term entirely by courtesy, for that day I was the creature of circumstance, with neither power nor volition—was quiet, well trained, and with a decided will of his own. Under no form of inducement would he move save in the footsteps of his predecessor. He early showed dissatisfaction with the weight of his load, and gave vent to a series of groans that were not tranquilizing. He also manifested a desire to go perilously near the precipice, and would rest apparently on nothing and at improper occasions.

The road is precipitous, but it is three and sometimes four feet wide, with angles and turns of surprising sharpness, but generally protected by stones, logs or masonry, and in many places made less fearful by a thick growth of under-brush. The horse on which I rode—I use the term entirely by courtesy, for that day I was the creature of circumstance, with neither power nor volition—was quiet, well trained, and with a decided will of his own. Under no form of inducement would he move save in the footsteps of his predecessor. He early showed dissatisfaction with the weight of his load, and gave vent to a series of groans that were not tranquilizing. He also manifested a desire to go perilously near the precipice, and would rest apparently on nothing and at improper occasions.

The view is grand, but appalling. Deep down in the mountain-walled gorge before us sleeps the valley; its beautiful glades, its peacefully glinting river, its dark green pines, its heavily timbered slopes, all hemmed in by cliff-encompassing domes. No change of time or circumstance can ever efface from memory this ride to Glacier Point. One misstep, a falling rock, and there could be no salvation. You have taken, as it were, your life in your hands.

Snow and Shrubs

When near the summit our path ran between snow drifts from four to six feet high. These banks were rapidly melting, augmenting the bodies of water which compose the different falls, and making the trails moist and slippery. The only shrub you see is a dwarf live-oak, manzanitas, and a few chinquapin bushes. The manzanita, with its pinkish white, wax-like and globe-shaped blossoms hanging in bunches, challenges our admiration. Save for beauty, these specimens are of but little use. The wood when young is soft, and is easily borne down and made crooked by the weight of the snow. That which grows upon the river bank is tall, lithe and straight, susceptible of a high polish when used for canes and ornamental purposes.

For four and a half miles we trudged this weary way; and then, when the summit was gained, we suffered disappointment, for the clouds which had hung at our feet all day long developed into a thick mist and completely hid the glories we had climbed so far to see. Encouraged by the custodian we waited, but only to see it become more and more impenetrable, and with beating, quaking hearts we took up the march for our descent.

Next Time Will be Different

Of the details of the return journey I am not sufficiently composed to write in a disinterested manner. The view is still there, each turn was made with precision, but the relief with which the base was reached told the tale of fear and suffering. When next I visit Glacier Point the trail will lead me to the summit, but the stage, four horses and a cautious driver will carry me from that eminence to Clark's. This little piece of information I gained, and will bestow upon those who follow me over that beaten but perilous track. Once and only once before had I seen my spouse under similar trying circumstances—then a score of years ago, when we bestrode what the people of Killarney facetiously termed “ponies.” Time has robbed his figure of the grace of youth and added to his avoirdupois, still the agility with which he mounted and the determination with which he avoided looking at what he came to see, made an indelible impression upon my mind, and I determined that as our horsemanship was only intended for show places, this, our second, should be our last appearance. Hence-forth those sights which cannot be reached by carriage or on foot will be forever unseen and unregretted by us. Truthfully has Starr King written, “Nowhere among the Alps, in no pass of the Andes, and in no canyon of the mighty Oregon range, is there such stupendous rock scenery as the traveler here lifts his eye to.” There is on every side an overpowering sense of the sublime. It is the crowning glory of all views. We are shut in by mountain walls, only three thousand feet we say, but so immense is everything that figures have lost their meaning, and everything is swallowed up and obliterated by the immeasurable stony heights that look down upon us. You could spend months viewing this scenic beauty, the memory of which is like the mercies of the Almighty, “new every morning and fresh every evening.”

It seems almost presumptuous for me to attempt a description of what the greatest minds of the century have acknowledged their inability to depict. The longer we gaze, the greater is our wonder. And in ending this imperfect sketch we might quote the words of James Vick, who gave as his impression that “the road to Yosemite, like the way of life, is narrow and difficult, but the end, like the end of a well spent life, is glorious beyond the highest anticipations.”

We Learn From Mr. Galen Clark

It was our very good fortune while in the valley to meet Mr. Galen Clark, a man who is an enthusiast in regard to its beauties, a compendium of knowledge concerning the different localities, and high and reliable authority in relation to formations and statistics. A New Hampshire man by birth and education, Mr. Clark was forced by ill health to seek the mild climate of this section. A love of adventure made him one of the first explorers, and for fourteen years he filled the responsible position of Guardian of the place. His love for the spot is genuine, his pride in it real, and with an interest which none can mistake he leads the visitor where everything appears in its best and noblest aspect. Under his guidance we looked upon Mirror Lake, and saw reflected therein the sun and its innumerable rays; marked the fanciful loveliness of Clouds' Rest when mirrored upon its bosom; drove where Yosemite dashes in broken and triple beauty for three thousand feet; and anon stood and listened with rapt attention to the sounds, which came like artillery, from the Bridal Veil when surged and dashed about by the roaring wind. For ten miles we followed the Merced river, amid rock and tree, until Cascade Fall was reached; then listened as the old man told in tender accents the story of the one dweller in that region who, broken-hearted by the infidelity of one he trusted, crept back to his dishonored hearth-stone, and was shot upon the threshold. The home he so fondly reared is now falling to decay. Many of the theories in regard to the glacial period, a prehistoric race, and kindred topics, Mr. Clark has imbibed from the conversation of learned visitors; but his own ideas are original, and he will give you with an uncommon degree of accuracy the time and cause of the falling of fragments, their weight, the devastation wrought by wind and flood, and convey to you in such unmistakable terms his fondness for the place that it is a pleasure to listen to the recital.

Mr. Thomas Hill, an artist of wide repute, whose studio at Wawona attracts many visitors, is also an enthusiast in regard to the charms of the Valley, and has transferred to canvas many phases of the remarkable spot. First, you may look, by means of his brush, from Inspiration Point, or see the scene when every peak is illumined by the setting sun. Again, you may stand and gaze with wondering eyes at the noble fall of water, or from beneath look up to the dome reaching almost to the heavens.

Mariposa Grove Big Trees

A visit to the remarkable group of big trees at Mariposa Grove concluded the experiences of this memorable week in April. Situated on the top of the mountain, they number six hundred—“the noble six hundred,” they may well be called. They are a variety known as Sequoia Gigantea, and partake of the nature of red-wood and cedar. I saw them ninety-nine or thirty-three yards in circumference, and sat in the stage drawn by four horses through one which only measures eighty-four feet. They are from one hundred and fifty to two hundred feet high, and show from their concentric rings or layers that they are over four thousand years old. The bark is soft and spongy and easily detached. The greatest devastation has been done by fire, and nearly every one is partially burned or disfigured. We asked regarding the prevalence of the destroying element, and were told that the herders, to rid the ground of pine needles, which are destructive to vegetation, start forest fires. These trees being old are highly inflammable, and, as a consequence, suffer there from. Since the grove has been the property of the state the most stringent regulations are observed, but, unfortunately, too late to prevent the wanton destruction of what may truly be termed a “wonder of the world.”