From The Expedition of the Donner Party and its Tragic Fate

Eliza Poor Donner Houghton

Chicago, A.C. McClurg and Co., 1911

Eliza Poor Donner Houghton (1843-1922 ) was the youngest child of George Donner, one of two Springfield, Illinois, brothers who organized the ill-fated California-bound emigrant party that bore their name. Eliza and her older sisters were rescued by relief parties that made their way to the stranded travelers at Donner Lake, but their parents perished, and the girls were left to make their way alone in the West.

Eliza Poor Donner Houghton (1843-1922 ) was the youngest child of George Donner, one of two Springfield, Illinois, brothers who organized the ill-fated California-bound emigrant party that bore their name. Eliza and her older sisters were rescued by relief parties that made their way to the stranded travelers at Donner Lake, but their parents perished, and the girls were left to make their way alone in the West.

The Expedition of the Donner Party and its Tragic Fate (1911) begins with Mrs. Houghton's account of her childhood and the family's tragic overland journey, and rescue. She continues with her life as an orphan, first at Fort Sutter, and then with a family in Sonoma and with her older half-sister in Sacramento. Eliza writes at length of the emotional scars caused by contemporary rumors of cannibalism among the Donner Party and offers full accounts of Donner family history as well as the background of her husband, Samuel Houghton.

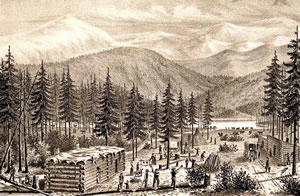

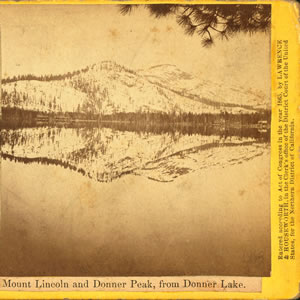

In this selection, Eliza recounts the miserable conditions at Donner Lake in the winter of 1846-1847 and her ultimate rescue.

Weather

Meanwhile with us in the Sierras, November ended with four days and nights of continuous snow, and December rushed in with a wild, shrieking storm of wind, sleet, and rain, which ceased on the third. The weather remained clear and cold until the ninth, when Milton Elliot and Noah James came on snowshoes to Donner's camp, from the lake cabins, to ascertain if their captain was still alive, and to report the condition of the rest of the company.

Meanwhile with us in the Sierras, November ended with four days and nights of continuous snow, and December rushed in with a wild, shrieking storm of wind, sleet, and rain, which ceased on the third. The weather remained clear and cold until the ninth, when Milton Elliot and Noah James came on snowshoes to Donner's camp, from the lake cabins, to ascertain if their captain was still alive, and to report the condition of the rest of the company.

Before morning, another terrific storm came swirling and whistling down our snowy stairway, making fires unsafe, freezing every drop of water about the camp, and shutting us in from the light of heaven. Ten days later Milton Elliot alone fought his way back to the lake camp with these tidings: “Jacob Donner, Samuel Shoemaker, Joseph Rhinehart, and James Smith are dead, and the others in a low condition.”

The First Death

Uncle Jacob, the first to die, was older than my father, and had been in miserable health for years before we left Illinois. He had gained surprisingly on the journey, yet quickly felt the influence of impending fate, foreshadowed by the first storm at camp. His courage failed. Complete prostration followed.

My father and mother watched with him during the last night, and the following afternoon helped to lay his body in a cave dug in the mountain side, beneath the snow. That snow had scarcely resettled when Samuel Shoemaker's life ebbed away in happy delirium. He imagined himself a boy again in his father's house and thought his mother had built a fire and set before him the food of which he was fondest.

But when Joseph Rhinehart's end drew near, his mind wandered, and his whitening lips confessed a part in Mr. Wolfinger's death; and my father, listening, knew not how to comfort that troubled soul. He could not judge whether the self-condemning words were the promptings of a guilty conscience, or the ravings of an unbalanced mind. Like a tired child falling asleep, was James Smith's death; and Milton Elliot, who helped to bury the four victims and then carried the distressing report to the lake camp, little knew that he would soon be among those later called to render a final accounting. Yet it was even so.

Gnawings of Hunger

Our camp having been thus depleted by death, Noah James, who had been one of my father's drivers, from Springfield until we passed out of the desert, now cast his lot again with ours, and helped John Baptiste to dig for the carcasses of the cattle. It was weary work, for the snow was higher than the level of the guide marks, and at times they searched day after day and found no trace of hoof or horn. The little field mice that had crept into camp were caught then and used to ease the pangs of hunger. Also pieces of beef hide were cut into strips, singed, scraped, boiled to the consistency of glue, and swallowed with an effort; for no degree of hunger could make the saltless, sticky substance palatable. Marrowless bones which had already been boiled and scraped, were now burned and eaten, even the bark and twigs of pine were chewed in the vain effort to soothe the gnawings which made one cry for bread and meat.

During the bitterest weather we little ones were kept in bed, and my place was always in the middle where Frances and Georgia, snuggling up close, gave me of their warmth, and from them I learned many things which I could neither have understood nor remembered had they not made them plain.

Playing With a Sunbeam

Just one happy play is impressed upon my mind. It must have been after the first storm, for the snow bank in front of the cabin door was not high enough to keep out a little sunbeam that stole down the steps and made a bright spot upon our floor. I saw it, and sat down under it, held it on my lap, passed my hand up and down in its brightness, and found that I could break its ray in two. In fact, we had quite a frolic. I fancied that it moved when I did, for it warmed the top of my head, kissed first one cheek and then the other, and seemed to run up and down my arm. Finally I gathered up a piece of it in my apron and ran to my mother. Great was my surprise when I carefully opened the folds and found that I had nothing to show, and the sunbeam I had left seemed shorter. After mother explained its nature, I watched it creep back slowly up the steps and disappear. Snowy Christmas brought us no “glad tidings,” and New Year's Day no happiness. Yet, each bright day that followed a storm was one of thanksgiving, on which we all crept up the flight of snow steps and huddled about on the surface in the blessed sunshine, but with our eyes closed against its painful and blinding glare.

Once my mother took me to a hole where I saw smoke coming up, and she told me that its steps led down to Uncle Jacob's tent, and that we would go down there to see Aunt Betsy and my little cousins.

I stooped low and peered into the dark depths. Then I called to my cousins to come to me, because I was afraid to go where they were. I had not seen them since the day we encamped. At that time they were chubby and playful, carrying water from the creek to their tent in small tin pails. Now, they were so changed in looks that I scarcely knew them, and they stared at me as at a stranger. So I was glad when my mother came up and took me back to our own tent, which seemed less dreary because I knew the things that were in it, and the faces about me.

Father's hand became worse. The swelling and inflammation extending up the arm to the shoulder produced suffering which he could not conceal. Each day that we had a fire, I watched mother sitting by his side, with a basin of warm water upon her lap, laving the wounded and inflamed parts very tenderly, with a strip of frayed linen wrapped around a little stick. I remember well the look of comfort that swept over his worn features as she laid the soothed arm back into place.

More Snow Then Sunshine

By the middle of January the snow measured twelve and fourteen feet in depth. Nothing could be seen of our abode except the coils of smoke that found their way up through the opening. There was a dearth of water. Prosser Creek was frozen over and covered with snow. Icicles hung from the branches of every tree. The stock of pine cones that had been gathered for lights was almost consumed. Wood was so scarce that we could not have fire enough to cook our strips of rawhide, and Georgia heard mother say that we children had not had a dry garment on in more than a week, and that she did not know what to do about it. Then like a smile from God, came another sunny day which not only warmed and dried us thoroughly but furnished a supply of water from dripping snowbanks. The twenty-first was also bright, and John Baptiste went on snowshoes with messages to the lake camp.

He found its inmates in a more pitiable condition than we were. Only one death had occurred there since our last communication, but he saw several of the starving who could not survive many days.

The number to consume the slender stock of food had been lessened, however, on the sixteenth of December, some six weeks previously, by the departure of William Eddy, Patrick Dolan, Lemuel Murphy, William Foster, Mrs. Sarah Foster, Jay Fosdick, Mrs. Sarah Fosdick, Mrs. William McCutchen, Mrs. Harriet Pike, Miss Mary Graves, Franklin Graves, Sr., C. T. Stanton, Antonio, Lewis, and Salvador.

A Party Sets Out

This party, which called itself “The Forlorn Hope,” had a most memorable experience … In some instances husband had parted from wife, and father from children. Three young mothers had left their babes in the arms of grandmothers. It was a dire resort, a last desperate attempt, in face of death, to save those dependent upon them.

Staff in hand, they had set forth on snowshoes, each carrying a pack containing little save a quilt and light rations for six days' journeying. One had a rifle, ammunition, flint, and hatchet for camp use. William Murphy and Charles Burger, who had originally been of the number, gave out before the close of the first day, and crept back to camp. The others continued under the leadership of the intrepid Eddy and brave Stanton. John Baptiste remained there a short time and returned to us, saying, “Those at the other camp believe the promised relief is close at hand!”

This rekindled hope in us, even as it had revived courage and prolonged lives in the lake cabins, and we prayed, as they were praying, that the relief might come before its coming should be too late.

Oh, how we watched, hour after hour, and how often each day John Baptiste climbed to the topmost bough of a tall pine tree and, with straining eyes, scanned the desolate expanse for one moving speck in the distance, for one ruffled track on the snow which should ease our awful suspense.

Only Beef Hide to Eat

Days passed. No food in camp except an unsavory beef hide—pinching hunger called for more. Again John Baptiste and Noah James went forth in anxious search for marks of our buried cattle. They made excavations, then forced their hand-poles deep, deeper into the snow, but in vain their efforts—the nail and hook at the points brought up no sign of blood, hair, or hide. In dread unspeakable they returned, and said:

“We shall go mad; we shall die! It is useless to hunt for the cattle; but the dead, if they could be reached, their bodies might keep us alive.”

“No,” replied father and mother, speaking for themselves. “No, part of a hide still remains. When it is gone we will perish, if that be the alternative.”

The fact was, our dead could not have been disturbed even had the attempt been made, for the many snowfalls of winter were banked about them firm as granite walls, and in that camp was neither implement nor arm strong enough to reach their resting-places. It was a long, weary waiting, on starvation rations until the nineteenth of February. I did not see any one coming that morning; but I remember that, suddenly, there was an unusual stir and excitement in the camp. Three strangers were there, and one was talking with father. The others took packs from their backs and measured out small quantities of flour and jerked beef and two small biscuits for each of us. Then they went up to fell the sheltering pine tree over our tent for fuel; while Noah James, Mrs. Wolfinger, my two half-sisters, and mother kept moving about hunting for things.

Relief at Last

Finally Elitha and Leanna came and kissed me, then father, “good-bye,” and went up the steps, and out of sight. Mother stood on the snow where she could see all go forth. They moved in single file,—the leaders on snowshoes, the weak stepping in the tracks made by the strong. Leanna, the last in line, was scarcely able to keep up. It was not until after mother came back with Frances and Georgia that I was made to understand that this was the long-hoped-for relief party.

It had come and gone, and had taken Noah James, Mrs. Wolfinger, and my two half-sisters from us; then had stopped at Aunt Betsy's for William Hook, her eldest son, and my Cousin George, and all were now on the way to the lake cabins to join others who were able to walk over the snow without assistance.

The rescuers, seven in number, who had followed instructions given them at the settlement, professed to have no knowledge of the Forlorn Hope, except that this first relief expedition had been outfitted by Captain Sutter and Alcalde Sinclair in response to Mr. Eddy's appeal, and that other rescue parties were being organized in California, and would soon come prepared to carry out the remaining children and helpless grown folk. By this we knew that Mr. Eddy, at least, had succeeded in reaching the settlement.