From Records of a California Family; Journals and Letters of Lewis C. Gunn and Elizabeth Le Breton Gunn

Elizabeth Le Breton Gunn and Anna Lee Gunn Marston

San Diego, California, 1928

Lewis Carstairs Gunn and Elizabeth LeBreton Stickney made their home in Philadelphia after their marriage in 1839. In 1849, Lewis Gunn left for the California goldfields with his wife and four children joining him two years later. Records of a California Family (published in 1928) begins with Lewis Gunn’s journal describing his journey from New Orleans to Mexico and then to San Francisco and his life as a miner on the San Joaquin River from1849 to 1850. Mrs. Gunn's letters chronicle her voyage around Cape Horn with four children in 1851 and their life in Sonora (1851-1861), where her husband published the Sonora Herald and owned a drugstore. She records the affairs of the family, newspaper publishing, and politics. The Gunns were longtime abolitionists, and Lewis's role in lobbying for California’s admission as a free state is recounted in the book. In 1861, the family moved to San Francisco, and the book closes with chapters by Anna Gunn Marston, their daughter, summarizing their life in Sonora, in San Francisco in the 1860s and her later experiences in San Diego.

Today, the Gunn Family presence is still felt in Sonora. Their family residence, built in 1850, was used as a hospital for years and then as a hotel called the Italia Hotel. In 1960, the hotel was remodeled and renamed the Gunn House.

In this selection, Anna Gunn Marston describes her childhood in 1850s Sonora and the purchase and operation of the Sonora Herald by her father.

Sonora

Although I was only eight years old when we left Sonora, I have many childish memories of the place, and especially of the old home, with its thick adobe walls, its wooden shutters, and the high balcony from which we saw such unforgetable scenes.

Although I was only eight years old when we left Sonora, I have many childish memories of the place, and especially of the old home, with its thick adobe walls, its wooden shutters, and the high balcony from which we saw such unforgetable scenes.

I must have been very young when the Digger Indians used to come into town and dance before the house. They wore high feather head-dresses and had grotesque stripes painted on their chests, and would grunt and dance and whistle through long reeds until we threw down some dimes.

A more gruesome recollection is of seeing a wagon pass the house in which were four Chinamen sitting on long wooden boxes; and mother had to tell me that those were their coffins, and that they were being driven out of town to a place at some distance, where they were to be hanged for the murder of another Chinaman. Whenever there was to be a hanging, which happened not infrequently in those days, mother closed the house and tried to make us stay in rooms from which we could not see the crowds of men and women that streamed past to sit on the hillside overlooking the scene.

The Summer of 1859

I remember that during the summer of 1859 Tuolumne County was greatly troubled by a number of burglaries, thought to have been committed by a band of roving Mexicans. The man who kept the ferry over the Stanislaus River was murdered and his money taken, and another at Chinese Camp was beaten and robbed.

Our own personal experience, probably with members of this band, was one of the most thrilling of my childhood. At this time father was away, and Chester was staying at a ranch in the mountains. One night we heard some one prowling about, talking softly to Rollo, our big dog that we had brought into the house for protection. The next day a young man who had been walking up from the store in the evening with Douglas and sleeping at the house, sprained his back and could not come.  This we feared might be the time when we would be attacked, and we became very nervous, as we had no close neighbors. Douglas came home early and the house was made as secure as possible. The wooden shutters on the windows, that had not been used for years, were closed and bolted; and the bar, a precaution of the early days, was laid on the floor between the front door and the hall partition, securely preventing the door from being opened; and Rollo's mat was laid at the back door, while he had the run of the kitchen and hall.

This we feared might be the time when we would be attacked, and we became very nervous, as we had no close neighbors. Douglas came home early and the house was made as secure as possible. The wooden shutters on the windows, that had not been used for years, were closed and bolted; and the bar, a precaution of the early days, was laid on the floor between the front door and the hall partition, securely preventing the door from being opened; and Rollo's mat was laid at the back door, while he had the run of the kitchen and hall.

A Hatchet and a Pistol

Mother allowed us girls to come into her room, and Sarah showed us a hatchet which she had hidden under the pillow of her cot. Mother insisted that we should go to bed at the usual hour, but even I could not go to sleep. Douglas, who had a pistol, probably did not undress. About midnight the dog began to growl, and to go back and forth from one door to the other, and Douglas heard low voices and a fumbling at the front door. He went out onto the balcony and asked what was wanted, and a man replied that he wanted to know the way to town. He was told to go out the gate and follow the street, which was perfectly plain; and after a few minutes, feigning to be intoxicated, he stumbled down the walk and went away. But Douglas kept the light burning throughout the night, and his pistol at hand; and as the dog made similar manifestations several times, we thought that there must have been some one else who stayed about but made no attempt to enter.

I think it was about this time that the brutal murder of a very good man, Judge Brunton, took place. His body was found on the lonely road to Poverty Flat. He was supposed to have been killed by some one against whom he had rendered judgment, and even a lawyer of the town was suspected. But the murderer was never brought to justice. I remember that the daughter of the judge, dressed in deep mourning, came to our house one evening, and that she said she heard a mysterious tapping on the head-board of her bed, and that she thought her father's spirit was trying to tell them something. Mother was very sorry that we should have heard this, and carried me off to bed, telling me that people often imagined things that were not so.

A Normal Childhood

I have mentioned these episodes from the lawless back-ground of the times in order to emphasize by contrast the orderly and happy environment which our parents created for us. Our free outdoor play, our pets, the books father chose for us, the many simple celebrations mother planned, the love and spirit of co-operation which they put into our home life, gave us a very normal childhood.

After the earliest years, mother had her flower garden in front of the house. At the side father planted an apple tree for each child, and here there was an irrigating ditch in which we often waded. Our playground extended to the high pine tree on top of the hill back of the house, beyond which we might not go. In springtime this hill was clothed with wild flowers of many kinds, among the loveliest of which were the deep rose-colored cyclamen (Dodecatheon ), the mariposa lilies, and a fragrant low-growing white jasmine.

A pleasant memory of the big pine is that the boys used to shoot at the cones, bringing them to the ground for us to get the nuts; and another that we used to sit there and watch Chester fly the huge kites that he made. Our donkey was often very obstinate about going up the hill, but he was always willing to go down to the barn with Sarah and Lizzie on his back, often tossing them over his head at the last, if they were not on their guard.

Mexican Mustang Liniment

Our goats were kept in a corral on the hillside, and we called them by names from the Greek mythology. When they were sold Douglas had an elaborate bill-of-sale made at the Court House, in which each goat was named and described, adding much to their value in the estimation of the country woman who bought them and signed her name with a cross. I cannot remember horses, but at some time we must have had one, for on a shelf in the barn another child and I found a bottle of "Mexican Mustang Liniment” and thought it would be nice to put some on our hair. The odor clung to us for a long time.

A reason why we were not supposed to go farther than the hilltop was that there was an abandoned mining shaft in the valley beyond. One day, attracted by "rooster heads,” as we called the wild cyclamen, Lizzie and I wandered into the valley and over the next hill. When we finally returned, we saw father standing with a rope in his hand and another man about to descend into the shaft, around which they had traced our steps. Father then carried me home weeping, and Lizzie, being the older one and more responsible for the worry we had caused, followed sadly.

I have a vivid recollection of one visit of my childhood. A family named Jarvis, a father and four sons, had come from the East and planted an orchard near Columbia. As they had ample means to provide the free use of water, they soon proved that all kinds of fruit could be raised there, and of the finest quality. They were people of culture, and had brought their furniture, pictures, and books, and had made a beautiful home. If they had only been nearer Sonora, it would have been a delight to mother to have known them better. We drove over one afternoon in a high buggy, Lizzie sitting on my little footstool at mother's feet. The supper table was a revelation of beauty to me. It was set for the large family with much shining glass and silver, and was lighted with many candles. Of the feast I remember only that it was not thought best for me to have the dessert of preserved plums and rich cream. It was late when we drove home by moonlight through the trees. Of the last year in Sonora there are a series of pictures in my mind, little related to each other. I think of Douglas as a man in the drugstore; of Chester as being helpful about the house and garden; and of Sarah as having suddenly grown to be taller than mother, and that she was much interested in clothes and in sewing on our Wheeler & Wilson sewing machine, one of the first brought to the town. Lizzie and her friend Lulu Brown treated me as a small child; they would not allow me to help cook with the little stove, which was Lizzie's greatest delight, but I was allowed to eat the failures, which were many. Lizzie was slender and agile, and able to walk on the top of fences and on stilts. I was very proud of her when she fearlessly mounted a riding-horse that some one had brought to the house, and frightened enough when she rode off down the street. As to stilts, no boy in town made and used as tall ones as Chester.

Bad Joke

I know that father considered Douglas a capable and conscientious clerk in the drugstore, but there was one occasion when he was tempted to play a joke, which he related with mingled shame and amusement. A big teamster came in, who asked him to prepare a seidlitz powder; and Douglas set the two tumblers before him without combining the contents. When the strangling man grasped the counter, with bulging eyes, and literally foaming mouth, Douglas clung to the counter on his side, so overcome with fear and contrition that he could not speak, and he was not relieved until the man was able to pour out the indignant stream of abuse which he so fully deserved.

When I was fourteen years old I returned to Sonora with my earliest playmate, Victoria Wright. We were on our way to Sugar Pine, in the high valley of the Stanislaus River, twenty miles above the town, where we were to spend Christmas at her father's sawmill. I called on Aunt Maria and Mrs. Hartwig, a German woman who wept when she saw me and told me that my mother had been very good to her. I found that our old home, somewhat changed, had become the county hospital.

A day's drive beyond Sonora brought us to a mountain summit, and from there we walked down a steep trail into the valley, where the river rushed along between great sugar pines, cedars, and oaks. I have many recollections of my weeks there: long walks in the invigorating cold, crisp apples, frost pictures on the windows, crashing thunderstorms, and at Christmas a garment of snow over everything.

1899 Return Visit

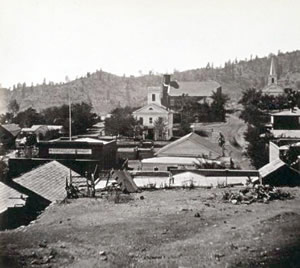

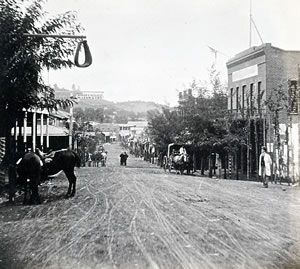

I went again to Sonora with my husband in 1899. I then appreciated the truth of what Mr. Charles Nordhoff had once told me, that my birthplace was the prettiest mountain town he had seen in California. We found it very picturesque, built on gently-sloping hillsides crowned with pines, the streets lined with locusts, poplars, and cork-elms, and pretty gardens full of roses and syringas in front of white-painted cottages. I recognized a few old buildings: father's drugstore, the City Hotel, and the Methodist church on the hill. In the Catholic churchyard nearby, made lovely by the many wild flowers growing between the grave stones, I read a number of familiar names.

Our old home, after being used for many years as the county hospital, was now being rebuilt for a residence. The changes were so decided that the deep window casings in the thick adobe walls were almost the only familiar feature. The hill behind the house seemed much lower, and the old pine tree was gone.

The Sonora Herald

The Sonora Herald was the first newspaper printed in the southern mining district. The first issue was on July 4, 1849. The press used was the pioneer press of California, which had already had an interesting history. It had been brought by ship from Boston to Monterey in 1832 by Augustine Zamorano, and was described as being of an early and crude type and as having had hard service before leaving Boston. "The frame, platen, ribs, and part of the bed were of wood, the bed on which the forms lay was of stone, and the screw by which the impression was taken, of iron and large enough to raise a building.” After the American occupation it was used by Colton and Semple to print the California Star, the first newspaper issued in California. Later paper and press were removed to San Francisco, where the Star was united with the Alta California. When improved machinery was purchased, the old press resumed its travels and was in turn used to issue the Placer Times in Sacramento, the first paper of the Interior, the Stockton Times, and the Sonora Herald. It was finally sold to the editor of the Columbia Star, who, however, failed to pay for it. When it was attached and sold under execution, it was bought in by my Father. But sympathizers with the editor of the Star removed it to the street and burned it during the night. The newspaper fraternity of the state was indignant at this proceeding, and protests appeared in the different journals which had been created through its use.