From My Grizzly Bear

Jessie Benton Frémont

Mother Lode Narratives, 1858

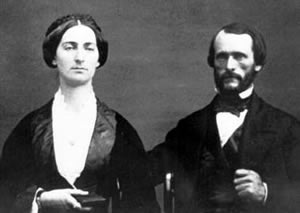

Jessie Benton Frémont – the daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton--was the wife of the famous explorer and soldier John C. Frémont and was largely responsible for the development of Frémont’s reputation as the “Great Pathfinder” of the American West. She was a primary author of Colonel Frémont’s expedition reports from the 1840s, and her contributions and engaging writing style, which were largely unknown to the general public, captivated the reader with descriptions of Frémont’s adventures in the West.

Jessie Benton Frémont – the daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton--was the wife of the famous explorer and soldier John C. Frémont and was largely responsible for the development of Frémont’s reputation as the “Great Pathfinder” of the American West. She was a primary author of Colonel Frémont’s expedition reports from the 1840s, and her contributions and engaging writing style, which were largely unknown to the general public, captivated the reader with descriptions of Frémont’s adventures in the West.

Jessie Frémont also published accounts under her own name. During 1858–1861, she lived in California’s Mariposa County on a huge estate that she called “Our Mining Place in the Lower Sierra.” There she wrote sketches that were later published as Mother Lode Narratives. These writings include this selection, “My Grizzly Bear.”

Bear Valley

Bear Valley was the name of the busy mining town nearest us on our mining place in the Lower Sierra. It troubled our sense of fitness to call a town a valley, but it was fixed by custom and fitness; for this had been a happy hunting-ground of the grizzlies. Acorns of the long variety, tasting like chestnuts, abounded here as well as the usual smaller varieties, while the rich oily nut of the piñon-pine made their delight. These acorns and piñones were the chief bread-supplies of the Indians also who did not give them up easily, and consequently bear-skeletons and Indian skulls remained to tell the tale to the miners, who came in to the rich “diggings” there. American rifles, then the pounding of quartz mills and strange shrieks of steam engines drove them away, and only the name remained.

To my objection of using “valley” and “town” as one and the same, I was told best let it alone or worse would follow, for there was a strong party intending to change the name of the place to “Simpkinsville,” and how would I like that? The postmaster was the Simpkins—a tall, “showy” young man with an ambitious wife much older than himself; he was a London footman and she Irish, active, energetic, with a good head, and with ambition for her Simpkins. That neither of them could read or write was a trivial detail that did not seem to disturb the public. Men would swing down from horse or wagon-box, go in and select from the loose pile of letters their own and those of their neighbors, and have their drink at the bar over which Simpkins presided (they kept a tavern and the post-office was only a little detail).

Branded F

But with the instinct of a man who “had seen the world” toward people of somewhat the same experience, the postmaster treated us with the largest courtesy, for everything with a capital “F” on it was laid aside for us. [This “F” was the brand on all the tools and belongings of the works—in these countries whatever else was defied, the brand had to be respected. –J.B.F.] Isaac, our part-Indian hunter, who generally rode in for the mail did not read either, and often had to make return-trips to give back what was not ours. It was in the time of Mr. Buchanan’s administration, and had Simpkins sent in a petition signed as it would have been by the habitues of his bar, of course so faithful a political servant would have been granted this small favor, of change of name. You may be sure I lay low in my valley to avert this cruel address on my letters.

I had never before gone up to this property, and now it was chiefly as a summer open-air and camping-out tour to be over in three months, when we were to return to Paris where all arrangements had been made for a three-years stay.

Although the bear had long disappeared from this favorite old haunt I felt nervous about horseback excursions. Mountains are grim things at best, but all those deep clefts and thickets in ravines and horrid stony hill-slopes barred me from any but the beaten stage and wagon-roads, with our cool, brave Isaac to drive me. However, there was one view Mr. Frémont wanted me to see which we could get only on horseback, with a short climb at the peak of the mountain. From the summit we could see eighty miles off the line of the San Joaquin River, defined by its broad belt of trees, running north and south parallel to our mountains; connecting the two were many mountain rivers crossing the broad plain and glittering like steel ribbons in the afternoon sun—the Merced, the Stanislaus, the Tuolumne and others; a turn of the head showed the peaks of the Yosemite thirty miles off, and lines of blue mountains back to the everlasting snow of Carson’s Peak—a stretch of a hundred and fifty miles.

A Rough Ride Up

It was a rough ride up, and rougher climbing after the horses could go no further and had to be left tied to trees with one man to watch them—only one other was with us; our party was only myself and my daughter with her father and the two men. We were growing more and more enthusiastic as glimpses of this rare view came to us. Mr. Frémont told us the distances, which only singularly pure mountain air could have let the eye pierce. “And the ear, too,” I said. “We must be three miles from the village and yet how near sounds the barking of that dog!”

Dead silence fell on our animated people. They listened, as the rough, low bark—broader and rougher even than that of a bull-dog rose again, sounding really close to us.

I never question any acts of some few people but I was surprised, and not too pleased, to find myself hurried back down the steep, stony peak with only, “It is too late to finish the climb—we must hurry—do not speak—keep all your breath for walking.” And hurry we did. I was fairly lifted along. Mr. Burke had disappeared and was now with Lee bringing the horses to meet us—the horses refractory.

A Dizzying Ride

Without a word I was lifted into the saddle—Mr. Frémont gathered up my reins himself and kept close to my side—and we fairly scurried down the mountains, I shamelessly holding to the saddle as the steep grade made me dizzy. This dizziness so pre-occupied me with the fear of fainting that I felt nothing else. We gained the stage-road by the shortest cut, and then a loping gallop soon brought us home, where I was carefully lifted down and all the consideration and care which they dared not give me on the hurried ride was now lavished on me.

I had been seriously ill not long before and could not understand why I was so roughly hauled along.

There was reason enough. It was no dog, but a grizzly bear that made that warning bark, and we were very close to it.

Weak Link in the Chain

My ignorance spared me the shock of this knowledge, but the practised mountain men knew it was not only a bear, but a she-bear with cubs. They knew she would not be likely to leave her cubs at that hour when they were settling for the night unless we came nearer or irritated her by talking and noises. Horses are terribly afraid of this powerful and dangerous animal, and one danger was that our horses would break away and run for safety leaving us to the chances of getting off on foot. There I was the weak link in the chain. My daughter was fleet of foot and so steady of nerve that she was told the truth at once, and did her part bravely in keeping me unaware of any unusual condition. Fortunately our riding horses were, each, pets and friends, and only required to be safe with their masters; Burke had got back instantly to help Lee, and once mounted we were moved by one intelligence, one will.

Very quickly our bright drawing-room filled with eager men gun in hand. Armed men rode down the glen intent on that bear—first coming to get all information of the exact locality, then to ride and raise the countryside for a general turnout against it. For everyone had kept from “the Madam” the fact that a she-bear had been prowling about for some time seeking what she could devour; and that she had devoured some and mangled more of “Quigley’s hogs”— Quigley having very fine and profitable hogs at a small ranch three miles from us.

Bear Wary

Lights frighten off wild beasts. I had no shame in illuminating the house that night. Men laughed kindly over it, but they all felt glad that I had come off so safely, and next day I was early informed that the cubs were all killed. The bear went as usual to Quigley’s for her raw pork supper, the digestion of a bear making this a pleasure without drawback, but the stir about the place was evident to the keen senses of the grizzly and the men watched that night in vain. Her tracks were plain all around about, and the poor thing was tracked to her return to her cubs. She had moved them—made sure they were all dead, and her instinct sent her off into close hiding.

The watch was kept up, but she was wary and kept away.

At length one dark night the Quigley people heard sounds they were sure came from the bear though the hogs in the big pen were quiet. They were stifled sounds blown away by a high wind. There was but one man in the house, and he said his wife would not let him go after them; it was so desperately dark the odds would be all against him.

The woman said she was not sure it was a bear. She half thought it was men fighting, an equally great danger in that isolated way of living. So they shut their ears and their hearts although human groans and stifled blown-away cries made them sure it was no animal.

The Morning Reveals a Death

The sounds passed on. In the morning they went to the wagon-road which ran near their enclosure and found a trail of blood. Followed up, it led to a little creek close by with steep clay banks. Dead, his face downward in the water, lay a young man in a pool of blood—shockingly mangled across the lower part of the body. His sufferings must have been great, but his will and courage had proved greater.

He had not been torn by a bear as was first thought, but by a ball from his own pistol. This was found, a perfectly new pistol, in his trousers pocket; the scorched clothing showing it had gone off while in the pocket. The trail was followed back, leading to a brook where he must have stopped to drink when the pistol, carrying a heavy ball, went off. Yet such was his courage and determination that he crawled that long way in a state plainly told by the place where he had rolled in agony—the last was where he made his vain appeal for help at the Quigley house. Perhaps he fell face downward into the shallow streams and was mercifully drowned.

His good clothing, a geologist’s hammer, and some specimens of quartz wrapped in bits of a German newspaper, told of an educated, worthy sort of man. But there was nothing to identify him, and the poor fellow was never inquired after. One of the many who came from afar with high hopes, and whose life was summed up in that most pathetic of words, “Missing.”

The grizzly had disappeared and was, I am told, the last ever known in that valley, which still has as postmark for the town, “Bear Valley”; it is to be presumed the succeeding post-masters have been men who knew the whole of the alphabet as well as the letter “F.”