Okei Ito

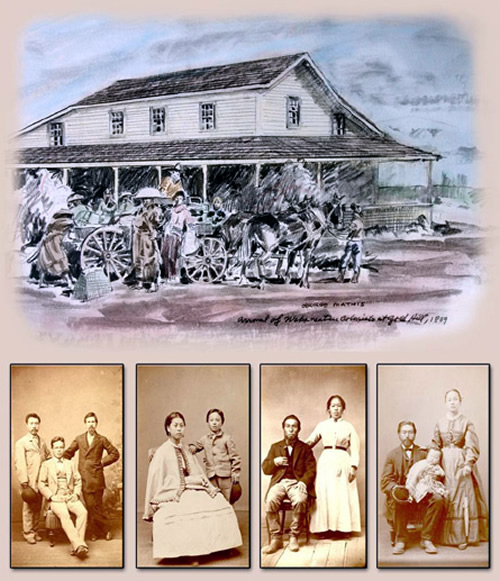

In June 1869, a most interesting company arrived near Coloma. The group included twenty-two Japanese samurai and a young woman named Okei Ito. In their possession were mulberry trees, tea plant seed, fruit tree saplings, paper and oil plants, rice, bamboo and other crops that they had brought from their Japanese homeland. With these items and an abundance of anticipation, this vanguard established the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony, which is believed to be the first permanent Japanese settlement in North America. The colony was the birthplace of the first naturalized Japanese-American and the only settlement established by samurai outside of Japan.

17th Century Policies

But the colony’s history had its origin earlier in centuries-old domestic Japanese politics. In the 17th century, the Tokugawa Shogunate, the feudal political structure that ruled the island from 1603 to 1868, adopted cultural isolation and prohibitions on foreign travel as their keystone policies. These policies reigned supreme for 250 years, until Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy forcibly established trade with Japanese ports in 1853-1854, primarily through American military intimidation. Perry’s foray opened the door to foreign cultural intrusion and by the 1860s, the Shogunate’s desired seclusion was crumbling.

The Tokugawa leadership attempted to stem the tide, but a local daimyo, or Lord, of the Aizu Wakamatsu Province publicly and dangerously disagreed with Shogunate policy and felt that some form of accommodation with the Westerners was a more prudent course. His name was Matsudaira Katamori. He was not alone as a few others in the Tokugawa Shogunate wished for modernization and nascent global outreach. Internal dissension was brewing

Katamori was friendly with the European diplomat John Henry Schnell, who was attached to the Prussian Embassy. Schnell also sold European-style weaponry. Katamori was one of his best customers and Schnell trained the provincial samurai in the use of European firearms. John Henry Schnell achieved great respect and even rank in the province as he was awarded a Japanese name, allowed to marry a Japanese samurai-class woman, and given the rank of General.

War of the Year of the Dragon

The rapid changes in Japanese society following Commodore Perry’s arrival led to bitter discord between the Tokugawa faction, which included the disaffected Matsudaira Katamori, and their enemies, who wished for a restoration of the Imperial Monarchy after decades of Shogunate rule. The result was the bloody Boshin Civil War of 1868-1869, a conflict also known as the War of the Year of the Dragon. In 1868, Katamori’s force of 4000 samurai was roundly defeated by the Emperor’s army of 20,000 soldiers at Aizu, Wakamatsu Province. Katamori surrendered and was sentenced to execution. His friend and supporter John Henry Schnell suddenly found his life in danger.

In April 1869, with Katamori’s financial support, Schnell arranged for a steam-powered clipper ship, the SS China, to carry some Wakamatsu refugees to the United States. Among the passengers were Schnell’s Japanese wife Jou and their daughter Frances, some of Katamori’s veteran samurai, and the 17-year-old Okei, the Schnell Family nursemaid.

Arriving in San Francisco

Upon arrival in San Francisco on May 20, 1869, the refugees were an exotic novelty. The San Francisco Daily Alta California newspaper gushed about Jou’s beauty and grace and that the cargo hold held 50,000 mulberry trees to be used for silk cultivation, six million tea seeds, and silkworm cocoons. The new arrivals also brought cooking utensils, swords, and a large banner bearing the Aizu Wakamatsu lotus blossom crest.

Within weeks, the colonists, under the direction of Schnell, purchased 200 acres and outbuildings in Gold Hill, just a mile from Coloma. The land had been purchased from Charles Graner, who had settled in Gold Hill in 1856. The settlers quickly began their daunting task of establishing a profitable agricultural colony. The mulberry trees and tea seeds were planted, other crops were cultivated (most notably, citrus, peaches, and other stone fruits) and dwellings began to appear. In January 1870, a correspondent for the San Francisco Daily Morning Call traveled to the Tea and Silk Colony and reported that the settlers had four carpenters in their company and they were

now engaged in erecting buildings for the party. The houses are to be twelve in number, dimensions thirty six feet by thirty, each containing four rooms, and built in the Japanese fashion with low, pitched roofs,… The partition walls are paper, the outer walls of wood; one room is to be used as a sleeping room, another as a kitchen, and the two others—in each house—or silk raising, where the worms will be kept and nursed and the silk reeled and otherwise manipulated.

Compliments on Japanese Culture

The correspondent commented favorably on Japanese ingenuity, neatness, intelligence and manners, but sadly found it vital to draw a negative comparison to the Chinese residents of the region, whom were regarded by the dominant Euro-American culture as dangerous and subhuman: "Take them all in all, they [the Japanese] are in every respect a superior race to the Chinese, and resemble them in no manner except their physical appearance."

The Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony flourished for a while. The colonists proudly displayed their products at the 1869 California State Agricultural Fair in Sacramento and the 1870 Horticultural Fair in San Francisco. But the colony faltered due to a series of momentous complications, including a prolonged drought, increasing water costs and competition, and, perhaps most importantly, the withdrawal of funding from Matsudaira Katamori. In 1869, the Boshin War ended in defeat for the Tokugawa Shogunate and brought the Meiji Restoration, the reinstallation of Imperial dynastic control. Katamori, sentenced to death during the war by the now victorious Meiji leadership, was surprisingly pardoned and chose to remain in Japan as a Shinto priest. With different personal circumstances and a newborn vocation, Katamori discontinued further funding to the Tea and Silk Colony.

Change in Land Ownership

In 1873, the Francis Veerkamp Family purchased the Wakamatsu lands. The colony was disbanded although several of the colonists remained on the property. The fate of only a few of the colonists is known. Matsunosoke Sakurai worked for the Veerkamps until his death in 1901. Masumizu Kuninosuke married Carrie Wilson, an African-Native American woman from Coloma. Kuninosuke died in 1915 but many of Masumizu and Carrie’s descendants still live in the region. And what of Okei Ito, the 17-year-old nursemaid of the Schnell family? She died in 1871 and was buried on the Wakamatsu Colony property. She was only 19 years old.

The story does not end there. In the early 1920s, Japanese Americans began tending to Okei’s grave and began emphasizing the importance of the Wakamatsu Colony in the history of Japanese immigration to the United States. Following the end of the Boshin Civil War and the Meiji restoration, rapid modernization and social upheaval rocked Japan. Many Japanese looked to a new start in new lands. Many of these searchers looked to the Wakamatsu experiment as a model for immigration that preserved cultural cohesion. The Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony experience is widely viewed today as the beginning of permanent Issei (first generation) settlement in the United States. By 1900, more than 20,000 Japanese were living in the United States and an estimated 10% of all California agricultural production was credited to the Japanese settlers.

First Japanese To Be Buried

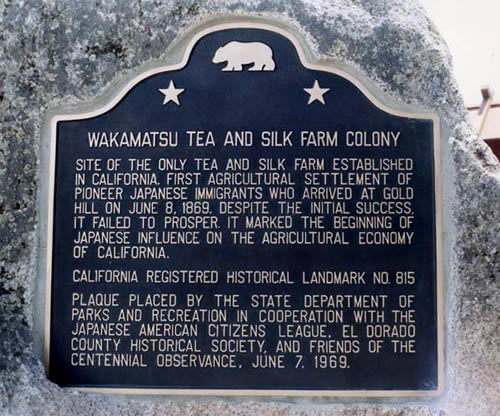

Okei Ito was the first Japanese buried on American soil and, in recent years, her gravesite has become a pilgrimage destination. In 1969, then California Governor Ronald Reagan designated the Wakamatsu Colony site as California Historic Landmark #815. Also, in 1969, the 100th Anniversary of the colony, Japanese American community leaders proclaimed the year as the "Japanese American Centennial." A commemorative ceremony at the Wakamatsu Colony featured participation from Matsudaira Ichiro, the grandson of colony financier Matsudaira Katamori, and the Japanese Consul General Shima Seichi.

In November 2010, the American River Conservancy purchased the 272 acre Gold Hill-Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony Farm with plans to preserve, protect and interpret the location’s significant and compelling social history and cultural legacy. The National Park Service has found the property to be "nationally significant." In 2009, local Congressman Tom McClintock introduced the Gold Hill-Wakamatsu Preservation Act (H.R. 4108) to safeguard the property. The legislation died in committee, but was reintroduced in 2011 by California Senator Barbara Boxer as Senate Bill 177, which was referred to the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources for consideration.

Sacramento Congressional Representative Doris Matsui has stated that "To many Japanese Americans, the Wakamatsu Colony is as symbolic as Plymouth Rock was for the first American colonists."

Image Credits:

- The Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony. Source: Collections of the American River Conservancy

- The gravesite of Okei Ito Source: Collections of the American River Conservancy

- Dedication of the Historical Marker at the Wakamatsu Colony June 7, 1969 – Governor Ronald Reagan second from left Source: Collections of the CSU Sacramento Archives and Library

- Historical marker at Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Colony Source: Collections of the American River Conservancy