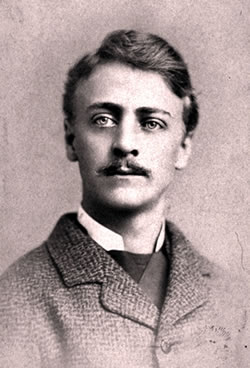

Burnette Haskell

Carl Sandburg, the famed poet and biographer, once wrote, "I’m an idealist. I don’t know where I am going, but I am on my way." In 1885, a fascinating assembly of idealists was on their way to a spectacular grove of Giant Sequoia to create an innovative social order. Their arrival brought turmoil and red-hot politics and led to the establishment of the first national park in California—Sequoia National Park in 1890.

Their leader was Burnette Haskell, a lawyer, publisher, and union organizer. As a young lawyer in San Francisco, Haskell inherited a newspaper from his uncle called The Truth. The newspaper became the primary vehicle for Haskell’s labor organizing. During the 1880s, Haskell and The Truth advocated the toppling of powerful economic interests and strengthening the power and impact of labor unions.

Through his publishing, advocacy, and research into political and social philosophy, Burnette Haskell was widely admired by a broad range of intellectuals and labor operatives, and became, in the words of labor historian Ira Cross, "without a doubt, the best read-man in the [San Francisco regional] labor movement."

Influenced by Danish Socialist

Haskell was particularly captivated by a Danish Socialist émigré named Laurence Gronlund. In 1884, Gronlund had published The Co-Operative Commonwealth in its Outlines: An Exposition of Modern Socialism, a political tome calling for collective, progressive communities and altering Karl Marx’s class struggle construct to encourage co-operative action as "the motor of history." Burnette Haskell was most certainly enthralled by passages like this:

When the Cooperative Commonwealth becomes an accomplished fact we shall have the full-grown Society; the normal state… It will be a social order that will endure as long as Society itself, for no evolution is thinkable except Organized Humanity and that is but Social-Cooperation extended to the whole human race.

Laurence Gronlund’s ideas were provocative and quite influential as Edward Bellamy incorporated some of the Gronlund’s philosophy into his popular 1889 social fantasy Looking Backward: 2000-1887. Bellamy’s novel was one of the best-selling books of the entire 19th century. It featured the story of Julian West, a young man from Boston who falls into a deep sleep in 1887 and awakens, Rip Van Winkle-style, 113 years later to discover a transformed American landscape, a Socialist Utopia much in the Gronlund model.

Starting Their Own Utopia

With a Gronlund-like co-operative settlement in mind, Haskell and his followers founded the Cooperative Land Purchase and Colonization Association.

In 1885, Association member Charles Keller heard reports that public land was available in the Sierra Nevada. The cooperative’s focus then centered on obtaining Sierra land for development and colonization. In September 1885, a team scouted property in the "Giant Forest," a remote grove of Giant Sequoia overlooking the Kaweah River watershed. Under the Timber and Stone Act of 1878, individuals could file with local and federal government to secure 160 acres of public land. The Association realized that one patch of land in such a remote location was practically worthless, but many adjacent claims would make for a large and potentially viable economic entity. By November 1885, constituents of Haskell’s Association had filed papers for fifty-three adjacent land claims in the Giant Forest.

It was a common practice in the late 19th century for these land act provisions to be abused by large corporate interests. By having individuals aligned with or employed by corporations filing single claims, the corporation could then turn around and gain control of large tracts of land for little investment. For this reason, the fifty-three claims of Haskell’s Cooperative Land and Colonization Association were suspicious to George Stewart, a local newspaper editor and former land agent. Stewart was also an ardent advocate of protecting the Giant Sequoia watersheds. Concerned, he alerted the Visalia Land Office of possible fraud by the cooperative. The Federal Government Land Office suspended the claims pending investigation.

Moving To a New Location

Unperturbed, the Association began anew in a location very near the Giant Forest. In 1886, 160 members of the group had settled in the foothills below the Giant Sequoia grove. They called their settlement "Kaweah Colony." Burnette Haskell had earlier begun publication of a colony newspaper unsurprisingly named The Commonwealth and in its pages he was enthusiastic about the colony’s location: "I think our people in the city should get away once in a while, aye, if only for a day, from the rottenness of the city to some place like this. Looking around me now, I can understand why those who live in the mountains are never fully enslaved."

In October 1886, the colony began its most difficult task—building a road to the Giant Forest, a task requiring back-breaking labor and thousands of feet of elevation change. After heated debate, the colonists reorganized as the Kaweah Co-Operative Commonwealth Company of California Limited. The Kaweah Colony built a school and began farming on homesteaded land outside the still disputed land claims. The road took three years to build. The colonists were confident that their land claims would be upheld.

Good Reports Provide Hope

In 1889, the road to the Giant Forest was nearly complete, and the colony received good news. Investigators issued an initial report stating that no evidence supported the objections of the Visalia Land Office. The Federal Land Office still had reservations, however, and action on this report was delayed. A second report, with the same conclusion, was issued, but there was still no resolution. The colonists remained confident. In 1890, a logging operation was begun at Kaweah Colony. Haskell bragged about this accomplishment in The Commonwealth: "The Eiffel Tower is 1,000 feet high, the Cologne Cathedral, 510 feet; the Great Pyramid but 460 feet; but our road has attained an altitude of nearly 7,000 feet. We are into the timber and the Kaweah Colony is no longer, in a material point of view, an experiment."

But George Stewart and his allies were hard at work as well. Stewart persuaded the local Congressman, Ventura’s William Vandever, to introduce legislation that would bring two townships under federal protection as a public park to protect some Giant Sequoia groves. Vandever introduced the legislation and it passed through Congress quickly. On September 25, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison signed the bill and established Sequoia National Park as the first national park within California. One week later, President Harrison received and signed a second bill creating Yosemite National Park. The Yosemite bill had been amended to expand the boundaries of Sequoia National Park, now all of one week old, to include the lands of the Giant Forest. Suddenly, the still disputed claims of the Kaweah Colony were within a National Park.

Beginning of the End

A few months later, the Federal Government Land Office finally issued its report on the Kaweah land claims. The report recommended that the colony claims be approved as the Yosemite National Park bill allowed for an exemption for "private lands" within the park boundaries. This recommendation was quickly rejected by the Department of Justice on the grounds that the disputed claims were not technically "private lands" at the time of the bill’s adoption. United States Cavalry troops were ordered to secure the park and the Kaweah Colony Trustees were arrested and convicted of "timber trespass."

By the beginning of 1892, the Kaweah Colony was nearing an end. Several colonists remained in the area and some worked in the neighboring National Parks. Burnette Haskell returned to San Francisco, where he died in a dilapidated shack, embittered and drug-addled.

Today, the only lasting remnant of the Kaweah Colony is the old Colony Mill Road, now a hiking trail. For more than thirty years, this road was the only vehicle route into the Giant Forest. To hike this path requires a difficult 10-mile trek featuring a climb of nearly 4,000 feet.

Image Credits:

- Burnette Haskell: Source: Collections of the University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft library

- Kaweah Colonists, Burnette Haskell on right with guns. Source: Collections of the University of California, Berkeley, Bancroft library