Sierra College Students Recover “King Tusk”

Auburn Journal, July 12, 1991

The sands of Egypt have yielded up the treasures of King Tut, but it is from the desert of Nevada that Sierra College has recovered “King Tusk.”

The sands of Egypt have yielded up the treasures of King Tut, but it is from the desert of Nevada that Sierra College has recovered “King Tusk.”

Dick Hilton, college geology instructor, has returned to the Rocklin campus with the 52-inch tusk, excavated from the Black Rock Desert by a group of 23 students who accompanied him on a week-long June dig. The perfectly formed tusk is believed to be from a mastodon or gomphothere, ancient ancestors of the elephant, which roamed approximately 10 million years ago when Nevada was a lush, fertile habitat.

After student assistants and college laboratory technicians prepare the discovery for exhibit, it will be kept at the Rocklin campus for scientific study and display. Hilton predicts the preservation, work on the tusk will be completed within the next six months, and it will be on display within the first months of 1992.

Other Creatures Also

In addition to the tusk, the group excavated two huge teeth from the giant creature as well as fossilized remains of ancient beaver, fish, rodents, deer and insects. Nearby were fossils from ancient rhinos, horses, camels, and even large cats.

“Through our search, we developed a picture of what this place looked like before the Sierra Nevada rose up, blocked much of the rainfall, and created the desert that exists today,” Hilton said.

As exciting as the tusk may be, the geologist observed, “It is likely the most important find from this dig won't be the tusk.” Hilton said although the elephant was the focus of the dig, it is possible a tiny jaw and tooth — perhaps a remnant of a prehistoric bat — may be a more valuable treasure. Because of their small size and fragile construction, bat fossils are more rare than those of the ancient elephants. The remote desert fossil site was first discovered during a Sierra College Science Club trip in the spring of 1988. Near the end of this three day exploration, some loose bone fragments were found on the desert surface by students Sharon Smith and Jennifer Fitzgerald.

Back for More

Another science club group returned to the site in Fall 1990. These students uncovered the upper end of the tusk and brought back an “elephant” tooth which was in very poor condition. Early this June, Sierra College students in a special summer geology field class headed for the Nevada desert knowing their goal was to bring back the tusk.

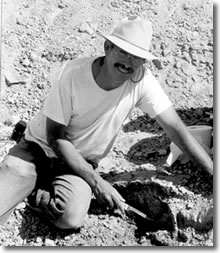

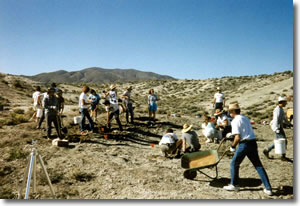

The students, from 19 to 47 years old, worked in shifts, using shovels, smaller hand tools, and even dental tools to excavate fossils from the pit that grew to be 17-feet long, 11-feet wide, and 5-feet deep. As yards of dirt were removed, other students examined samples to locate the less conspicuous fossils embedded in the rock. Hilton pointed out that the relative positions of the different fossils in the pit offered clues about which creatures and plant life coexisted, and which preceded or evolved after another. As the smaller fossils were removed, they were stored in boxes marked with the date, location and level of their discovery.

The first "elephant" tooth excavated on this dig was badly worn, but a second molar, removed intact, may provide scientists with enough information to definitely identify the creature as a mastodon, or its smaller, more rare predecessor, the gomphothere. The fossilized tusk is complete but contains countless tiny fractures which would cause it to crumble were it not treated with chemical solutions to bond it together. To stabilize the tusk so it could be safely extracted and transported to the Rocklin campus, Hilton and his team carved at the surrounding dirt until only an earthen “cradle” was left holding the fossil. Then the exposed top of the tusk was wrapped in foil and the fossil and “cradle” were covered with a burlap and plaster cast, which, when completed, distinctly resembled a small sarcophagus.

The Fossil is Named

After Hilton stared at the completed cast for a while, he called for a set of marking pens and began drawing on the top of the plaster package. The final decoration bore a strong similarity to the famous golden sarcophagus of King Tut, complete with headdress and smiling face. Then Hilton first pronounced the find, “King Tusk!”

Elizabeth and Michael Haydu, a young student couple from Roseville, spent the week digging at the pit and exploring another area about a mile away where they uncovered another deposit of fossils.

“This is a lifetime opportunity,” Elizabeth responded when asked about the trip. “We moved up from San Francisco about three years ago, and this trip has helped us meet new friends who share our interests.” The trip required considerable planning for the couple, who had to arrange for the care of their children, Jennifer, 10, and Gabriel, 3-1/2.

Students agreed that among the unexpected benefits of the trip was a viewing of the Aurora Borealis, the famous “Northern Lights,” usually seen only at more northern latitudes. The 20-minute display of red and white streamers of light occurred on Tuesday, June 4, at about 11 p.m. (Many scientists associate this phenomena with solar storm activity.) In addition, students observed wild antelope, mustangs, eagles and other desert animal life. They also saw a variety of desert wildflowers, produced by the late spring rains.

Humans Traveled Here Also

The area also offered visible reminders of human life which had lived in or traveled through the region. Some students located a beautifully crafted two-pronged fork, likely left by an early settler who moved west along the well-traveled pioneer trail through the Black Rock Desert.

Another exceptional relic of the past appeared to be a small, melon colored arrowhead. This object was dated from 10,000 to 12,000 years old by representatives from the Desert Research Institute and from the Bureau of Land Management who paid official visits to the dig site. While the Sierra College party had the required permits from the BLM to remove the fossils from the pit, the human artifacts belong to the state of Nevada and were photographed and left where they were discovered. At the end of the week, when the fossils and gear were removed, the site looked much the same as it did when the group arrived. The pit had been refilled and the ground smoothed over.

Diverse Learning

When asked what he felt his students had learned, Hilton had a long list. “They were exposed to Basin and Range geology, desert plant and animal life, meteorology, paleontology, and climatology,” he said. “And they also had to learn how to live together and cooperate in a desert environment.”

It is evident Hilton feels a certain pride in the growth of his students. On the trip back to campus student Bonnie Wunner of Nevada City asked the geology teacher for the approximate age of a rock formation the van was passing. When he estimated it was formed 20,000 to 30,000 years ago, the student remarked with surprise, “Oh, then it' s not that old.”

“When they start responding like that,” Hilton said with a smile, “you know you've taught your students something about geology!”

Additional Photos