Hetch Hetchy Politics—Preservationist, Provincial, Personal, and Perhaps Post-Partisan—in the 2000s

by Rick Heide

Author, Editor

The morning of November 6, 2012, dawned with high hopes among the band of preservationists hoping to restore the Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park. By that night, they had suffered a devastating political defeat.

It was among the bigger setbacks to the cause since the dam—on the Tuolumne River in the National Park—was first proposed over 100 years ago and John Muir led the first fights against it. Their Initiative was emphatically rejected by an electorate of over 300,000 voters in one of the most-liberal and most-environmentally-conscious big cities in the nation.

And then, by all appearances, it got worse for the Restore Hetch Hetchy campaign. Over the next couple of years, other political events, a big Yosemite-area fire, and an even-bigger California-wide drought seemed to “pile on” and further damn their dam-removal plan. The current balance of political forces looks decidedly grim for the pro-restoration cause.

And yet … In the latter months of 2014, the small-but-determined movement seems not only undeterred, but positively energized. Personal experiences in the High Sierra, over many years, and political struggles playing out over decades can also inform one’s outlook. And a “David v. Goliath” struggle over Mono Lake—only 35 mountainous miles east of Hetch Hetchy, as the California gull flies—helps me, at least, think longer-range about two fights in the Range we know as “The Range of Light.” Perhaps there are other ways of viewing the medium- and long-term Hetch Hetchy political outlook.

San Francisco’s Proposition F

Still, the magnitude of that electoral defeat in November 2012 should not be underestimated. In over a century of political struggle over the fate of Hetch Hetchy Valley, few days had seemed more hopeful than November 6, 2012. Excitement had been building for months among people working to drain the dam that had long inundated the “mountain temple” so admired by nature lovers, writers, photographers, and great painters of the West like Albert Bierstadt and William Keith.

Several preservationist, environmental, and wilderness organizations—led by the Restore Hetch Hetchy group—had decided to go over the heads of government officials. They had collected over 15,000 signatures to qualify a ballot measure, appealing to the very San Francisco citizens who own the Hetch Hetchy water system.

Other articles in this journal will deal with the many, often-complex, long-running issues concerning Hetch Hetchy. But, on the main issue in Proposition F, to put it crudely: Proponents claimed the majestic Hetch Hetchy Valley could be restored, the dam could be breached, and the water stored outside the Park, without San Francisco and other customers suffering any loss of Tuolumne River water. The City of San Francisco government argued that the plan was illogical, too-expensive, and—without the dam in the Park—the City “would suffer water shortages 1 out of every 5 years.”

In many ways, Proposition F was a cautious first step. It asked the voters of San Francisco to merely authorize an $8 million study—costing a bit under $10 per resident—to explore the feasibility of draining the big reservoir in the National Park. It called for studying ways to store Tuolumne River water further downstream, outside the National Park, and various other conservation measures.

Proposition F did not commit the City to any concrete (or, more-to-the-point, concrete-breaching) action on draining the dam in Yosemite. That more-momentous and more-expensive question would have required another separate vote, by those same citizens, after the study was completed.

Over many decades, there had been many public-opinion, editorial, legislative, administrative, and legal battles over the Valley. But, in over 80 years, nowhere near this many people had been empowered to have a direct say over the fate of the Hetch Hetchy Valley.

In the end, almost 75,000 San Francisco citizens voted for the Restore Hetch Hetchy study. But nearly 250,000 S.F. voters opposed it, over three times as many. Only 23.1% voted Yes on Prop F, while No votes were 76.9% of the total.

On a Chaotic California Water-Map, San Francisco Has a Very-Valuable Asset

In California, since soon after the Gold Rush, there has been—and still is—a mad scramble for rights to water. In the early days it was Miners v. Everybody Else and Private Water Companies v. Everybody Else. Today, from a “macro” level, you have North v. South, East v. West, and the tripartite Local v. State v. Federal contests. And then we also have Urban v. Rural, Farm v. Fish (& Fowl & Plants), Delta v. Southern Central Valley, Crop v. Crop, Water “Exporters” v. Water “Importers,” and literally thousands of other relatively-“micro” conflicts of interest.

You could say there is a patchwork-quilt of arrangements, except I have never seen such a disorderly, even messy, quilt. Usually involving several layers of government, almost every local water agency has a situation that is different from its neighboring entities. So the phrase “All politics is local” is particularly apt regarding California water.

Few responsibilities of local governments are more fundamental than providing water. And it is understandable that each entity fights fiercely for its share of water—a necessity of life.

San Francisco, surrounded by saltwater on three sides, has little fresh water of its own. Certainly it does not have enough to sustain a major American city. Since the first months of the Gold Rush, when its population started exploding, San Francisco was already importing water in significant quantities. At first it came in casks on boats across the Bay from Marin County.

In 1887, the newly-formed Turlock Irrigation District [T.I.D.] and Modesto Irrigation District [M.I.D.] won rights to Tuolumne River water. This was natural, because the Tuolumne ran through their area. But, although very far from the river’s path, the City of San Francisco also won copious Tuolumne River water rights and, later, permission to build a major dam in Yosemite National Park. San Francisco’s massive Hetch Hetchy water system, which starts in the Park and travels 167 miles, is even able to provide water to about 1,800,000 customers in 26 other Bay Area towns and cities, double its number of City of San Francisco customers. Its High Sierra power plants also help provide hydroelectric power for City facilities like the Municipal Railway, S.F. General Hospital, the City’s airport (SFO), public schools, parks, and municipal buildings. And the City also sells Hetch Hetchy power to Turlock, Modesto, and the big “for-profit” Northern California utility, Pacific Gas & Electric [PG&E]. (The vast majority of the City’s power is provided by a corporate utility. Private homes and businesses in San Francisco get their power from PG&E.)

So Hetch Hetchy is a huge asset for the City, the 3rd-largest municipal water district in California. Virtually every drop of tap water in San Francisco comes from the Hetch Hetchy system. And quite a few nearby cities—including Silicon Valley stalwarts like Palo Alto, Menlo Park, Mountain View, and Redwood City—also receive from 88% to 100% of their water from the Hetch Hetchy system.

California’s Big 3 in Washington, D.C.—Formidable Foes of Restoration

While the Turlock and Modesto districts have also been leery of changing the status quo, the fight against even studying Hetch Hetchy dam-removal has long been carried mainly by San Francisco. Three Californians in Washington, D.C., have, for decades, been formidable defenders of the established Hetch Hetchy system arrangements. These powerful politicians, whom I call “California’s Big 3 in D.C.,” were first elected in, respectively, 1982, 1987, and 1992 to represent all or part of California in the Capitol. And all have continued being re-elected and gaining seniority in the House and Senate ever since.

California politics is unique in a number of ways, often in pioneering ways. For instance, back in 1992, California was the first state to ever elect two women to represent their state in the U.S. Senate. Those women were the still-current U.S. Senators from California, Dianne Feinstein and Barbara Boxer.

California is also the only state, so far, to have a woman lead a major political party in the U.S. House of Representatives as either Minority Leader or Speaker of the House. The former Speaker, and now Minority Leader, is Rep. Nancy Pelosi. With lots of seniority and representing the most-populous state, I think it is fair to say that never before in U.S. history have three women from a single state wielded more power in Congress.

In addition to being trail-blazers for women in elected office, Senators Feinstein and Boxer and Leader Pelosi share something else. All three Democratic officeholders have long-standing ties to the City and County of San Francisco. And while San Francisco was California’s biggest city until a few years after the 1906 Earthquake and Fire, it is now only the state’s 4th biggest city in population. It is unusual for a state to have both its U.S. Senators and its most powerful Representative so closely identified with only their state’s 4th largest city. This is a situation that gives San Francisco outsized political influence in our nation’s Capitol.

Of the three women, only Senator Barbara Boxer is not a long-time San Francisco resident. She lived 16 miles north of “The City,” in Greenbrae, for most of her adult life and first won elected office as a Marin County Supervisor in the 1970s. But, before that, she worked as an aide to the influential San Francisco Democratic Congressman Phil Burton. And for 10 years—as a member of Congress in the 1980s and early ’90s—her North-Bay-based District included part of San Francisco.

Rep. Nancy Pelosi, like Senator Boxer, was born “back East.” But her political training began as a child in a political family. Her father was a U.S. Congressman and then Mayor of Baltimore. Soon after moving to San Francisco in 1969, Pelosi began working in local politics. Like Boxer, she was also a protégé of Rep. Phil Burton. And, a few years after Burton’s death, she was elected to his old seat, encompassing most of the City. She has represented San Francisco in Congress ever since 1987.

Senator Dianne Feinstein has been a San Franciscan since birth. She first won elected office to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1970. (As the city and county are the same entity, what would be the City Council in most cities is called the Board of Supervisors.) She became the first woman President of the Board in 1978. Later that year she became the first woman to be Mayor of San Francisco, after the tragic assassinations of Mayor George Moscone and her fellow Supervisor Harvey Milk, then the nation’s foremost gay officeholder. She actually heard shots and found Milk’s dead body in City Hall, then led a shocked, grieving city through very trying times. She was an elected City official for 18 years, serving 9 of those years as Mayor.

“California’s Big 3 in D.C.” are, on most issues, highly rated by environmentalists. But they also share a common view about one of San Francisco’s most-prized assets, its far-flung water system. While Feinstein—who was responsible for running the system as Mayor—is the most outspoken on the subject, all three women strongly oppose breaching the City’s dam in Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park.

Why the Focus on San Francisco Voters (Rather than the State or Federal Government)?

An outside observer might ask why the Restore Hetch Hetchy organization focused on San Francisco voters in 2012. It is what you might call the “home court” of “California’s Big 3 in D.C.” It is also a city that might have a vested interest in keeping their long-ago-hard-won victories in California’s “Water Wars.”

Additionally, the ostensible owners of Yosemite National Park are every one of America’s citizens. Yet slightly less than 1% of Americans get their water from the Hetch Hetchy water system. And San Franciscans are a smaller sub-set of this “One Percent.” Why appeal to only about 1/3rd of 1% of American voters? And why pick the very people who also happen to be among the main beneficiaries of the existing arrangements?

But, looking at the political history over several decades, one can see that the preservationists had their reasons.

Hetch Hetchy decisions rest primarily with the National Park’s manager (the federal government), the water system’s owner (San Francisco), others entities also holding long-established rights to Tuolumne River water (the Turlock Irrigation District and Modesto Irrigation District), and, to a lesser extent, other Bay Area cities to which San Francisco sells Hetch Hetchy water.

In 2005, California’s Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger authorized a preliminary study of draining the reservoir in the Park, bringing the issue back into mainstream politics after an 18-year hiatus. It was a bipartisan effort as the Governor worked across the aisle with Lois Wolk—a Democratic state legislator from Davis known for her pro-restoration views—and other Democrats and Republicans in Sacramento.

Apparently both supporters and opponents found things to like in the 2006 state report. It concluded that removing the dam was feasible, while providing adequate water downstream. However it also concluded that, though more thorough study was warranted, it might be an expensive proposition. But no further state action was taken. By 2014, though California state officials have a big say in its water policy, most legislators and staffers in the Capitol in Sacramento concede that—due to the historic/legal oddity of the Hetch Hetchy system’s status—in this case the state’s role is more advisory. Historically, in fact, most political struggles over the Valley have been at the federal level.

Still the Schwarzenegger state study helped raise the issue to fairly-widespread public attention again. Before that, the issue had been quiescent among the general public since the last time there was a Californian in the Oval Office, way back in the 1980s. President Ronald Reagan’s administration and Interior Department—not generally seen as pro-environment, but supportive of Yosemite and Hetch Hetchy Valley—had put a study on decommissioning the dam in the budget in 1987. At that time “California’s Big 3 in D.C.” lacked seniority and were either not present or that powerful in Congress. Then-Congresswoman Boxer had been in Congress for only 4 years and Congresswoman Pelosi for only 2 months. Meanwhile, future-Senator Feinstein was still back in San Francisco serving as Mayor. But, from there, Mayor Feinstein strongly objected to the study, calling Hetch Hetchy the City’s “birthright,” and Congress did not fund it.

By the 2000s, at least the upticks in public discussion over Hetch Hetchy were getting more frequent.

In 2004, President George W. Bush’s Republican administration proposed raising the rent the City paid the federal government for Hetch Hetchy from $30,000 a year (a rental rate unchanged since the 1920s!) to $8 million. They reasoned that the City made a lot more than $8 million by selling H.H. electricity to other utilities. That proposal went nowhere in Congress.

Then, in 2007, the Bush administration called for $7 million to study draining the reservoir in the National Parks budget. Congressman Dan Lungren—a Republican representing parts of Sacramento and Solano counties in the Central Valley and Alpine, Amador, and Calaveras counties in the Sierra Nevada mountains—issued a fervent call for its passage. He wrote in the Sacramento Bee that “For eight decades Americans have been deprived of this national treasure; now it is time to restore the Hetch Hetchy Valley.” But he was not joined by that many other legislators. Later, when Congress stripped the funds from the bill in committee, the Sacramento Bee, a newspaper that supports the Valley’s restoration, editorialized (in occasionally purple prose) that:

Ever since Nancy Pelosi of San Francisco became House speaker, it was clear Bush’s proposal would go nowhere, and that John Muir would remain heartbroken, rolling over in his grave. Pelosi and her powerhouse counterpart in the Senate, Dianne Feinstein, cling to fears that draining Hetch Hetchy would endanger San Francisco’s water and power supplies …. [O]ne day, with less conflicted leaders in Congress and a more visionary president, the nation will realize the wisdom of restoring Yosemite ….

By 2011, four years later, some political facts-of-life had switched in the nation’s capital. The President, Barack Obama, was a Democrat while the Speaker, John Boehner, was a Republican. But—whether anybody was less-conflicted or more-visionary, or not—the struggle to restore Hetch Hetchy was no closer to being won.

With “California’s Big 3 in D.C.” still wielding substantial power in Congress, a Democratic president seemed less likely to antagonize a heavily-Democratic big city’s representatives. The House of Representatives—returned to Republican control after the landslide election of 2010—was also in a different ideological stance than when it was in the majority during the Bush administration. The new House, with many Tea Party-backed “small-government” Republican insurgents, was now not as prone to support federal infrastructure projects. (And spending money to remove or bypass existing infrastructure was probably even further off their radar.) In 2011, it seemed even-more-unlikely that Congress would act to drain the reservoir in the Park.

And after many decades of appeals to Washington, D.C., the upshot was that the Valley remained underwater. So the Restore Hetch Hetchy activists decided on a totally different tactic.

They concluded that, legally, San Francisco did not need Congress’ approval to empty its City-owned reservoir in the Park. The City could vote to drain it and return the Valley to the National Park Service, so the N.P.S. could then restore it. And the Restore Hetch Hetchy folks felt the political terrain was favorable for them.

Many of Restore Hetch Hetchy’s activists were Californians, so they could concentrate their efforts close to home. The state had, for decades, been a leader in environmental legislation. (While the nation’s “carbon footprint” has increased by about 50% over the past few decades, California’s remained almost flat. This remarkable feat was largely due to pioneering, often bipartisan, California state environmental legislation and regulation.)

Of California’s big cities, San Francisco probably had at least as many environmentalists-per-capita as any other. (San Francisco has been a leader in “green” municipal measures and uses less water, roughly 88 gallons-per-person-per-day, than any big city in the state.) And, though millions of people from all over America and the world visit Yosemite, San Francisco has long been home to a relatively-high percentage of people who know and love Yosemite. San Franciscans were also even much-more-likely to visit the much-less-traveled Hetch Hetchy region of the Park, due to a city camp located near the reservoir (more on that later). According to the San Francisco Examiner, a few months before the election, Restore Hetch Hetchy financed a poll, showing 46% of San Franciscans favored draining the dam, within striking distance, with 48% opposed.

As Mike Marshall, then the head of Restore Hetch Hetchy, put it in a 2011 interview with the National Parks Traveler:

[O]ur legal research has shown that the voters of San Francisco, the people of San Francisco, can vote to restore Hetch Hetchy, and that’s an electorate in which Dianne Feinstein does not hold a whole lot of sway, and it’s a decision-making process that’s much more winnable for us.

Underestimating Feinstein’s “Sway” and Overestimating Hetch Hetchy’s Centrality to the Environmental Movement

Apparently, Mike Marshall grossly underestimated Senator Feinstein’s “sway” in the City of San Francisco, as well as that of Boxer and Pelosi. It turned out that Mayor Ed Lee and every single member of the 11-person Board of Supervisors would oppose Proposition F. (In the City’s left-of-center but still-very-fractious politics, such unanimity on the Board is indeed a rare thing.) So did Congresswomen Jackie Speier and Anna Eshoo, who combine to represent part of San Francisco and most of Hetch Hetchy’s water customers in nearby Peninsula cities and towns. All living former S.F. Mayors opposed Prop F. San Francisco business groups, labor unions, neighborhood groups, and organizations representing the City’s many ethnic groups also opposed the measure. It appeared, at least in 2012, that Hetch Hetchy dam-draining might be the metaphorical “3rd rail” of San Francisco politics, one that its politicians dare not touch, lest they be (again metaphorically) “electorally-electrocuted.”

Additionally, while Senator Boxer was not on the same 2012 ballot as Prop F, both Pelosi and Feinstein were.

While only 23% of San Francisco voters favored the restoration study, Rep. Pelosi won 85% of the votes in her San Francisco District. As for Sen. Feinstein, statewide she won the most votes for a Senate seat ever recorded in U.S. history, breaking Sen. Boxer’s previous record set in 2010. And of all California’s counties, Feinstein ran best in San Francisco, winning 88% of the vote. So it seems evident that even quite a few supporters of restoring Hetch Hetchy voted for Feinstein and Pelosi, despite both women’s staunch opposition to restoration.

The Yes on F people could cite the well-informed support of several retired superintendents of Yosemite. They thought restoration was both feasible and highly-desirable. And an impressive number of environmental organizations were listed in support of the 2012 ballot measure. But some of the biggest national pro-environment groups were not among them.

Most notable by its absence was the venerable Sierra Club. Perhaps the Club’s largest chapter, the Bay Area Chapter, could not agree on a position on Proposition F, so the Sierra Club sat out that fight.

This was significant because the Sierra Club was founded in San Francisco in 1892 by, among others, John Muir. He was the Club’s first president, serving over 20 years, until his death in 1914. And, by all accounts, the passage of the 1913 Raker Act—authorizing the dam in the Park—was the most painful defeat in Muir’s life.

Now the small group he helped build from scratch, initially to protect the Sierra Nevada, has become one of the most influential environmental organizations on the planet. It claims hundreds of thousands of members, has chapters in every state, and fights for environmental causes all around the world. Yet in the Sierra Nevada’s most-loved National Park it could not come to the aid of the Hetch Hetchy Valley in 2012.

Clearly, for some of the bigger pro-environment organizations—even including the one Muir founded—the issue of Hetch Hetchy restoration was now a marginal one.

In the Election’s Wake, a Few More Political Setbacks

While unable to take a stand on Prop F, the Sierra Club was quite active in many states in the 2012 election. In one California congressional race, according to press reports, the Sierra Club donated a whopping $650,000 to try to unseat Rep. Dan Lungren, one of the few outspoken congressional supporters of restoring Hetch Hetchy. They did it, not because of Hetch Hetchy, but because they felt Lungren’s own overall environmental record—and that of the 2012 Republican Party—was not a “green” one. They were especially upset at his support for increased oil and gas exploration and his stands on other issues of global warming. This showed that, for the Sierra Club, a bigger environmental picture now easily trumped the Hetch Hetchy cause for which their founder had fought a century before.

In one of the most expensive House races in U.S. history, Dr. Ami Bera, a Democrat, eventually won a very close election over Lungren, though the final outcome was not clear for weeks. While Hetch Hetchy was not a major issue in the campaign, Lungren’s loss removed the most forthright California Republican voice in Congress for its restoration.

Then, even in the afterglow of their decisive electoral victory, the City of San Francisco decided to raise the bar even higher for the preservationists. In a January 2013 article titled “Effort to Drain Hetch Hetchy Dealt Major Setback,” the San Jose Mercury-News reported:

In a move that could be the political death knell for environmentalists’ efforts to drain Hetch Hetchy Reservoir in Yosemite National Park, the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission has approved a plan to block the draining of the famed reservoir unless the 26 cities and water districts in San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Alameda counties that receive Hetch Hetchy water give their approval. “It’s a fairness question,” said Michael Carlin, deputy general manager of the commission. “They are paying two-thirds of the bills. They are two-thirds of our customers. We need to … [be] fair and equitable to all our customers.”

Whatever its merits, the rule would certainly increase the degree of difficulty. Apparently the City’s P.U.C. found a 77%-to-23% win too close for comfort. So—unless this P.U.C. plan is overturned in court—if Restore Hetch Hetchy decides to try the local-election approach again in the future, it could no longer concentrate on a single city of roughly 820,000 people. It would instead need to appeal to about three times as many voters, in a population of over 2.5 million people in 27 political jurisdictions.

Then, a year later in early 2014, Rep. George Miller, a senior Democrat, announced his impending retirement. He and Rep. John Garamendi both represent Districts that include much of the California Delta, a region that is very sensitive to California water issues. Miller and Garamendi, both Democrats, are now perhaps the leading advocates of restoring Hetch Hetchy in California’s Democratic congressional delegation. So, not long after losing the Republican Lungren, the very-thin ranks of crusaders for the Valley in Congress also lost the Democratic Rep. George Miller in January 2015.

Land of Fire

And then “Mother Nature” seemed to weigh in…. In 2013 it had been 110 years since Mary Austin’s magnificent book, The Land of Little Rain—about the East Side of the Sierra Nevada—first appeared. Meanwhile it had been a mere 43 years since James Taylor recorded the classic folk-rock song “Fire and Rain” (which is not about the Sierra Nevada at all). I have thought about both of these wonderful works of art while fire and drought have struck California in late 2013 and 2014.

And when reading the news about these big events, at least on the surface, it seemed they were helping insure that the Hetch Hetchy reservoir would not be drained in the foreseeable future. At times it seemed that even Mother Nature was piling on reasons not to breach the dam in the National Park.

First, the fire.

Even in wet years, California’s Sierra Nevada and much of the American West experience a number of forest fires. In testimony before Congress in 2013, Thomas Tidwell, head of the U.S. Forest Service, said that fire season in the West now lasts two months longer and destroys twice as much land as 40 years ago.

In mid-August—a few weeks after Tidwell testified, and after a couple of dry winters—a wildfire known as the “Rim Fire” started near Yosemite National Park. A hunter’s illegal campfire got out of control in the Stanislaus National Forest, east of Groveland, and burned just 40 acres the first day. But, abetted by drought, high temperatures, and rugged, hard-to-reach terrain, in a day-and-a-half it burned 10,000 acres. Then it really took off, burning 100,000 acres in four days, spreading into the National Park, and burning a total of over 250,000 acres over the next two months.

The Rim Fire turned out to be the biggest fire in the Sierra Nevada’s recorded history. It was fought by 5,000 firefighters and was big enough to even create its own weather system.

Among the many losses, one felt personal to our family and to generations of many other families. Since 1922, the City of Berkeley’s Camp Tuolumne has been located on the South Fork of the Tuolumne River, high in the Sierra Nevada. All the structures at that summer family-camp—where our daughter Cedra first worked away-from-home as a teenager—were burned to the ground. Once news of the Camp’s destruction spread, about 300 people of all ages spontaneously gathered for a candlelight vigil in Berkeley to celebrate memories of what one person called “the happiest place on earth.”

Like Berkeley’s city camp, San Francisco’s Camp Mather is also within 10 miles of the National Park. It is just 9 miles from the dam and the Hetch Hetchy Valley. Camp Mather started as a sawmill camp when the dam was being built and has been a getaway for San Franciscans since 1920. Much like Camp Tuolumne, “To call Camp Mather beloved is an understatement,” as the San Francisco Examiner put it. But, while the Rim Fire burned to the very edges of Camp Mather—coming at it from all 4 directions over 3 days and burning all around it—fire crews were able to make a brave stand and it suffered only minor damage.

A number of my friends and I have either camped or stayed in cabins in Camp Mather. My daughter Cedra first breathed high Sierra air on a weekend at Camp Mather in 1972, when she was only 3 months old. And, like many people based at Camp Mather, we took a long day hike. So I carried her with me into the Hetch Hetchy back-country, before returning for the night back at Camp Mather. The Hetch Hetchy back-country was, and is, awe-inspiring.

Located in a deep canyon, surrounded by mostly-roadless and heavily-forested wilderness, and in extremely steep high-elevation terrain, few major dams in America are harder to defend from wildfires than Hetch Hetchy. And although the conflagration at Camp Tuolumne was an emotional one for Berkeley, at least Berkeley does not depend on Tuolumne River water or power. (Like Oakland, Richmond, and many other East Bay cities, it relies on water from the Mokelumne River, which is dammed further north and stored at a lower elevation, many miles from the National Park.)

For San Francisco, both its water supply and a substantial amount of hydroelectric power were menaced by the Rim Fire. According to the Examiner, the fire “burned most of the southern edge and part of the northern side of the reservoir.” There were big worries about water quality, though so far the reservoir’s water seems to be quite-potable, in the post-fire months. (Ironically, the ongoing drought that enabled the fire to spread to Hetch Hetchy, may have helped save the water’s purity. Had there been a normal wet winter right after the fire, there might have been massive mudslides, carrying ash and pollutants into the reservoir.) The Rim Fire also knocked out two of the City’s three High Sierra power plants for a few weeks. All of this led to a very unusual governmental response.

California Governor Jerry Brown understandably declared a State of Emergency for the mountain areas where the Rim Fire was burning in the Sierra Nevada. What was unusual was that he also declared a State of Emergency in San Francisco County, over 150 miles away from the fire.

If San Franciscans needed a reminder of their reliance on Hetch Hetchy water and power, this was it. And the Rim Fire evoked dark thoughts about 1906. Only a few American cities have experienced a fire that remains such a large part of the city’s collective consciousness. (The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and the Oakland Hills Fire, that devastated both Oakland and Berkeley in 1991, spring to mind.)

In fact, in the early 1900s, Muir and the preservationists thought they had defeated the idea of a dam in Yosemite. The 1906 Earthquake and Fire, and national sympathy for the City, helped resurrect the idea of building the Hetch Hetchy system. The City then even built a grandiose “Pulgas Water Temple,” complete with Greek and Roman columns, to celebrate the place, in Redwood City, where Hetch Hetchy water first reached the Bay Area in 1934. As the City’s water department puts it, “With vivid memories of the fire that had raged unchecked after the Great Earthquake of 1906, the city rejoiced in its new secure, plentiful supply of high quality drinking water.”

As San Francisco’s big fire was over a century ago, probably nobody alive today remembers it. But most people who had a family member present at the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire have a “family story” about it. In fact, while nobody in my family was yet in California back then, even we have a story about it. Chances are that I, my siblings, and cousin would not have been Californians, absent the 1906 Fire. Our grandfather, an architect, moved from the state of Washington to San Francisco a few months after the Fire destroyed almost half of the City’s buildings. August Heide—who was recruited to help rebuild San Francisco—and his wife were the first of five generations in my family to make our homes in California.

Even today, Camp Mather and Hetch Hetchy are, in a sense, outposts of San Francisco in the High Sierra. They are, particularly for long-term San Franciscans, part of the City’s identity. And the Rim Fire threatened that identity.

Land of Little Rain

As I write in Autumn 2014, the current California drought is now in its third straight dry year. And this third winter was, by far, the driest. Average statewide rainfall in the 2013 calendar year was the lowest in over 130 years, ever since such records were first kept. (While most of the nation underwent a cold, snowy, and wet “Polar Vortex” winter, the drought also hit some other states in the Southwest. But as we are focusing on Hetch Hetchy, we will only deal with California here.)

Most of the state is listed as being in extreme or exceptional drought, the two worst possible categories, by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency [NOAA]. Still, on a scale of human suffering, California’s current plight is surely nothing like the droughts in China in the late 1870s and 1900s that killed tens of millions of people.

Nor is it as tragic as our own country’s 20th Century Dust Bowl that forced so many farm families—mainly in Oklahoma, Texas, and Kansas, including my future-father-in-law from tiny Radon, Oklahoma—to abandon their farms. In the 1930s, many of these farm families, despite being derided as “Okies” and subjected to intense discrimination, migrated, with virtually nothing, to then-wetter and more-fertile California. They and other agricultural workers from all over the U.S.A.—and as far away as Mexico, Japan, the Philippines, Armenia, Italy, Switzerland, India, Central America, the mid-Atlantic Azores, and elsewhere—joined longtime Californians and did the hard labor to help make California our nation’s leading agricultural state. (Of course, massive district, state, and federal water projects enabled them to farm and ranch in many arid areas of semi-desert and desert land. Without those water projects, California would not be #1 in agriculture.)

For now, in 2014, almost all Californians can turn on the tap in their homes and water still flows. Even lawns and gardens, in general, were still being watered, though some were much-browner, and some lawns and plantings were no longer kept alive. And, in a state where there are over 600 separate water districts—some decidedly not winners in the Water Wars that have been going on in California for over a century-and-a-half—some small districts have undergone the deprivation and expense of trucking in drinking water.

California’s water woes actually took a slight turn for the better in late February and March 2014 with some late rain and snow. But California’s drought was already way-too-big to be solved by these late-but-welcome storms. On April 21, the Sierra snowpack—a huge determinant of California’s water supply—was only 18% of normal for the date. (That very-low number was still an improvement, up from 12% of normal in January.) And California’s ultra-dry winter had already attracted national attention.

On February 1, 2014, B. Lynne Ingram, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at U.C. Berkeley, told the New York Times: “We [in California] are on track for the worst drought in 500 years.” (That dire prediction will probably not happen, at least in 2014. But if the 2014-15 winter is also very dry, the 500-year-worst might easily be achieved. Perhaps 2014 could end up as only the 3rd or 4th worst drought year since records started in 1880.)

Twenty days later into winter, on February 20, 2014, Timothy Egan wrote, also in the New York Times, that “when you build a society with a population larger than Canada’s, and do it with one of the world’s most-elaborate plumbing systems, it’s a fragile pact.” Egan continued:

The whole fantasy of modern California has long been dependent on an audacious feat of engineering. You could drain the Owens Valley to allow Los Angeles to metastasize. (See “Chinatown.”) You could grab water from Yosemite to keep San Francisco alive. And you could move all that snowmelt up north to the south, and feed the world.

When it works, it’s a marvel. Golden Gate Park is green. Los Angeles has a river (sort of). The fragrance of fruit trees fills Fresno. But what if there is no snow, no rain, and nothing left in the aquifers underground? To date, going back to the start of its water year last July, Los Angeles has received 1.2 inches of rain. Yes, for the year. San Diego will soon notch its driest winter ever. And 80 percent of the state is in extreme drought.

Egan concluded that California would get through it, but “not without significant pain.”

A lot of that pain is being felt by farms and fisheries, both of which need and use quite a bit of water. Agriculture uses over 80 percent of California’s developed water. And in a drought, that industry, livelihood, and way of life, will probably be hurt the most. Seasonal farmworkers, economically vulnerable under the best of circumstances, faced high unemployment among their ranks this year. President Obama came to the Central Valley, partly to announce measures to ameliorate some aspects of their worsening plight.

The California Farm Bureau estimated that from 400,000 to 500,000 acres out of 6 million acres of Central Valley farmland would be left fallow this year. The upper number is roughly double the area of the huge Rim Fire. Entire fruit, nut, and olive orchards—where trees take several years to grow and become productive—were left to die for lack of water this year. Many farmers and ranchers needed to cut back and some faced even going entirely out of business. Fish stocks, from the little Delta Smelt to the bigger Pacific Salmon, shrank. People in either the commercial or recreational fishing industries, already reeling the past few years, also faced more economic pain.

The Turlock Irrigation District cautioned its customers that this was the worst 3-year period since the T.I.D. was formed in 1887. Both Turlock and the Modesto Irrigation District share the Don Pedro Reservoir with San Francisco—downstream on the Tuolumne at a much-lower elevation, and holding over five times as much water as the dam in the National Park. And the T.I.D., M.I.D., and San Francisco, among the Water Wars’ biggest winners, are in much better shape than most California water districts. Still, the T.I.D. and M.I.D. planned to send their farming customers only half their usual allotment of water and to discourage usage by also increasing the price.

Though, like all Americans, their citizens faced higher food prices and scarcity of some types of produce due to the drought, some California water districts felt the least pain. These include the cities of San Francisco and Los Angeles—which were already big cities with lots of political clout and the ability to finance huge water infrastructure projects—back when water rights were being disputed over a century ago. These cities have almost-priceless assets in the Hetch Hetchy system, starting in Yosemite National Park, and the Owens River system, starting high in the Eastern Sierra.

At no time are the values of these assets more obvious than in times of drought.

Dam Politics During a Drought

As the San Francisco Bay Area has become more Democratic in recent decades, Eastern California—including the Sierra Nevada, the Northeastern mountains, the Southeastern desert, and much of the Central Valley—has become reliably Republican.

Congressman Tom McClintock is a Republican who represents a big swath of the central Sierra Nevada, including most of populous Placer County, the California side of Lake Tahoe, much of the Gold Country, and all of Yosemite National Park. In an interview with Breitbart News on March 7, 2014, Rep. McClintock discussed the drought, blaming the state’s water woes on Democratic administrations in D.C. and Sacramento, and the Democratic majority in the U.S. Senate:

We are being governed by people who are out of their minds …. Droughts are inevitable—they are nature’s fault. Water shortages are our fault.

Among other measures, he called for building the Auburn Dam in his District—a planned project on the American River that was abandoned decades ago—and raising the height of the Shasta Dam up north that would double Lake Shasta’s capacity.

When I called his office and asked whether Rep. McClintock agreed with his former neighboring-Republican-Congressman Dan Lungren on restoring Hetch Hetchy, his spokesman was blunt:

The Congressman [McClintock] respects Dan Lungren, but Lungren was way out of line on this. We need more storage, not less. San Francisco needs the water. Tearing down the dam would be lunacy.

The spokesman assured me that this was Rep. McClintock’s position.

Rep. Devin Nunes is a Republican who represents a big part of Fresno County and all of Tulare County, the two leading counties in agricultural production in the entire United States. He has every reason to want more water to flow south to Central Valley farms. But while Rep. McClintock acknowledged the inevitability of droughts in California, Rep. Nunes seemed to be in denial about a couple of major issues. According to the New York Times of Feb. 1, 2014, Rep. Nunes said:

Global warming is nonsense …. There was plenty of water. This has nothing to do with drought. They can blame global warming all they want, but this is about mathematics and engineering.

This seemed jarring coming within weeks of stories in the Los Angeles Times and Fresno Bee, major state newspapers widely read in his District. On the global front, the L.A. Times reported that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency announced that average global temperatures in 2013 had tied for the 4th highest year since 1880. NOAA noted that every single year since 1976 had been above the 20th Century average, 37 warm years in a row. And the 10 hottest years since 1880 had all come between 1998 and 2013. Whatever its causes, this would seem to constitute a global warming trend over the last few decades.

Much closer to his home, Rep. Nunes represents part of the City of Fresno in Congress. The Fresno Bee reported that Fresno recorded only 3.01 inches of rain in all of 2013. Since records were first kept in 1878, it was the driest year in Fresno’s entire history. That would seem to constitute drought. In his New York Times column on February 20, Timothy Egan acidly commented that “Nunes apparently skipped science class.”

Still, those California Republican Representatives who accepted there was a drought were able to make common legislative cause with a drought denier like Rep. Devin Nunes. The Sacramento-San Joaquin Valley Emergency Water Delivery Act (HR 3964) was co-sponsored by all 15 of California’s Republican Congressmen. I say “Congressmen” because—while 18 of California’s 38 Democratic members of Congress are women—I was surprised to learn that, even in 2014, not a single one of the 15 California Republicans in Congress is a woman. (This will change in early 2015 when Mimi Rogers, newly elected from Orange County, will become the one woman in California’s Republican congressional delegation.)

HR 3964 would end, suspend, or change environmental regulations to send more water to southern Central Valley farms and cities. It would also make it easier to build or augment dams, though the fiscally-conservative Republican plan would provide no federal funds for construction.

Rep. Kevin McCarthy has a geographically-diverse District. It includes the forests of the Southwestern Sierra Nevada, Sequoia National Park, the booming City of Bakersfield, Central Valley farms, oil fields, and even part of the Mojave Desert. He is the most powerful Republican in California’s Congressional delegation. Rep. McCarthy was the Republican Whip, #3 in the House leadership after Speaker Boehner and Majority Leader Eric Cantor, and adept at unifying the party’s factions. (In late summer of 2014, the popular McCarthy replaced Cantor, who had surprisingly been upset in his Virginia primary, as Majority Leader. McCarthy then ascended to the #2 spot among all House Republicans in only his 4th term, the first person in congressional history to become Majority Leader so soon. His political rise has been remarkable.)

McCarthy’s influence was a key to rapidly passing HR 3964 on February 5, 2014. Once it passed, Rep. McCarthy said:

It is unacceptable that vital water supplies are being forced out to the ocean instead of going to our cities. The issue demands immediate attention and today’s vote represents House Republicans’ commitment to putting families over fish …. I urge Senator Boxer and Senator Feinstein to use their seniority and influence to demand that Majority Leader Harry Reid schedule California water legislation for a vote on the Senate floor as soon as possible.

One critic called the House measure a “political power play that undermines years of delicate negotiations.” And California’s Democratic Governor Jerry Brown said it “falsely suggests the promise of water relief when that is simply not possible, given the scarcity of water supplies.”

Hoping not to be “out-dammed,” Democrats in Congress proposed some dam building of their own. Their plans generally call for federal, as well as state, funds. Rep. John Garamendi (a major supporter of draining the Hetch Hetchy reservoir) called for a big new Sites Reservoir to store Sacramento River water northwest of Sacramento. Democratic Rep. Jim Costa of Fresno proposed three new or augmented dam projects to aid his Central Valley District. On March 23, 2014, Rep. Costa told the Associated Press:

You cannot recycle in enough quantities to irrigate half the nation’s fruits and vegetables. It’s really that simple.

In the Senate, Boxer and Feinstein favored their own California drought bill, which passed by unanimous consent. So both branches were able to pass a drought bill.

Still, despite some House-Senate closed-door negotiations and hints that some common ground existed, Congress went on a long summer recess without agreement on a California drought bill. Despite a desire to say they had done something about the drought before election season, the partisans were unable to make a deal. So California House members—every one of them up for election in 2014, both Democratic and Republican—were unable to claim any tangible federal progress toward drought relief by Election Day, even amidst one of the worst droughts in state history. This allowed their opponents to credibly pose in nearly-dry or bone-dry reservoirs, accusing the incumbents in Congress, of either party, of accomplishing nothing toward alleviating the water crisis.

This was doubly embarrassing because, unlike the hyper-partisan congresspeople in Washington, D.C., the California legislature had succeeded in putting aside partisanship on this very pressing issue. Governor Jerry Brown worked with legislators of both parties to put a massive $7 billion bond issue on the November 2014 ballot. The measure was a combination of dam building, underground storage, conservation of various sorts, habitat protection, some help for the critically-ill San Joaquin River and Salton Sea, and a variety of other measures. It was deftly crafted to win over a host of often-clashing interest groups. It is not often that the state’s Farm Bureau and the Nature Conservancy, labor unions and the Chamber of Commerce, the Delta Counties Coalition and big Southern California water districts, and the state Democratic and Republican parties all join together on a water issue.

The proposal passed the State Senate unanimously. In the Assembly, only two members voted No. The total vote in both chambers was 77-2, an amazing “big-tent” result. It was interesting that one No vote was a liberal from the very-wet North Coast. The other No was from the opposite end of the state, a conservative who represents much of the very-dry Mojave Desert. Yet every other legislator voted for it. The big water-bond issue was then passed by the voters by a wide, roughly 2-to-1, margin. (It did not, of course, mention Hetch Hetchy.)

Meanwhile, back in Washington, D.C., it seems likely that if any California drought legislation eventually emerges out of House-Senate negotiations, it will at least encourage building new and enhanced dams.

Paradoxically, though anathema to most people in the environmental community, building and enhancing California dams might—in the medium- and longer-term—help to create a political climate in which Hetch Hetchy might be restored. If additional water storage is built—hopefully also including more storage in underground aquifers, where evaporation is less of a problem, and less disruptive to the land above it—the Hetch Hetchy reservoir might seem less essential to California’s water security. This would be particularly true if the Don Pedro Dam, lower down on the Tuolumne River, were raised. This could help assuage the fears of the Turlock, Modesto, and San Francisco water agencies (and their customers in other cities). A modest rise in that dam, with its already-much-bigger capacity, could someday make the much-smaller Hetch Hetchy reservoir in the National Park seem superfluous.

Still, needless to say, in the drought year of 2014, few elected officials, either Democrats or Republicans, want to talk much about removing any of California’s 1,400 named dams. Not even the one in a National Park. (There are also many hundreds of more-obscure dams in the state.) In 2014, the “3rd rail” metaphor—for the danger of supporting Hetch Hetchy dam removal among San Francisco elected officials—might well be extended to almost any elected officials in the entire state.

And Yet … There Is an Elected Mariposa County Supervisor Who Looks and Speaks a Lot Like John Muir

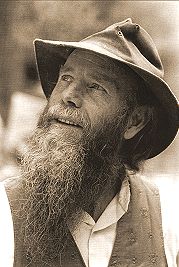

There is, however, one elected official who talks a lot about Hetch Hetchy. Like two other California politicians who earlier called for studying how to restore the Valley—Governor-and-then-President Ronald Reagan and Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger—he is also an actor. If you saw Ken Burns’ beautiful 6-part 2009 documentary, The National Parks: America’s Best Idea, on PBS television, you may remember Lee Stetson. He was the bearded man who read the words of John Muir, complete with the impeccable Scottish brogue.

Lee Stetson has portrayed Muir for about 30 years, in several plays he has written, relying heavily on Muir’s own words. He takes his plays on the road and also presents them each summer in Yosemite National Park. Over a quarter-of-a-million people have seen his plays there. And chances are that a fairly-high percentage of people who have seen one or more of his plays support restoring Hetch Hetchy. For they are quite emotionally-compelling on the subject of saving the Valley and Muir’s deep sense of loss upon passage of the Raker Act.

Stetson is one of three elected officials who are closest to Yosemite National Park. In each case, the Park constitutes a big part of their respective Districts. Yosemite is located in three California counties. From north to south, Tuolumne County Supervisor John Gray, Mariposa County Supervisor Stetson, and Tom Wheeler, a Madera County Supervisor, represent the entire Park. Stetson’s District 1 includes Yosemite Valley and the Park’s other major (and free-flowing) river, the Merced River.

As an avid environmentalist—elected to office in 2010, a year when Republicans made huge gains nationally—Stetson stands out for more than the length of his beard. He won office in Mariposa County, where Republican presidential candidates have carried the last 5 elections and which voted for Rep. McClintock, one of the most-conservative members of Congress. He credits a constituency which cherishes living in one of the most breathtaking areas on earth, and particularly people who work in the Park or along the Merced River, with helping him win office. (He declined to run for re-election for the term starting in 2015, but will be replaced by Rosemarie Smallcombe, a like-minded successor whose campaign he supported.)

It is an office in a small mountain county. But a man who has devoted a lot of his life to “spreading the news” about John Muir and Hetch Hetchy has been elected to that Mariposa County office.

There Might Be Another Way to Look at that 2012 Election in San Francisco

When I was playing pickup basketball if we got beat 77 to 23, I would readily admit we got “whupped.” That is surely how I felt when I heard the results of the 77% No vote on San Francisco’s Proposition F in 2012. It seemed like a “whupping.”

But, over time, I am thinking more about the formidable, but also-trusted, political figures arrayed against Prop F, the imbalance in money spent, a sense of self-interest in keeping a functioning system going, pride in their City’s incredible feat of engineering, even a bit of nostalgia for the “can-do” spirit of bygone San Franciscans.

If my fellow pickup players and I had played, say, an NBA team and lost 77-23, maybe we would not have felt so bad. We might have even been proud that we could score 23 and hold them to 77. And—given the court on which the electoral game was played and the big-league forces they were playing against—perhaps the Restore Hetch Hetchy team did very well to score 23 in their first game on that court.

And Maybe Another Way of Looking at the Drought

Our political leaders’ almost-knee-jerk answers of more-and-higher-dams to questions raised by California’s 2011-2014 drought leave the immediate political prospects for restoring Hetch Hetchy in the worst shape in years. And yet—along with “Fire and Rain” and The Land of Little Rain—I keep thinking of the phrase “A crisis is a terrible thing to waste.” Paul Romer’s incisive maxim can be relevant in a number of realms, perhaps including the politics of water scarcity, climate change, conservation, dam removal, and wilderness preservation/restoration.

As weeks of the 2013-2014 Winter, without any significant rain, stretched into months, I started thinking more about water, water policy, and personal water conservation than I had in decades. Like many people who were in California in 1976 and 1977—the worst previous drought in my lifetime—I had adjusted to the shortages back then and was quite frugal with water.

Then 1978 was a very wet year and the crisis eased. Unfortunately, over the next few years, I gradually went back to casually wasting water. I am not proud of this, but I don’t think my evolution-and-devolution as a careful consumer of water was all that unusual. A few of my friends permanently changed their water usage. But I’m afraid that I, and most of my fellow Californians, returned to many of our previous profligate water ways.

Three decades flowed by before a very-dry winter made me think much about doing my bit to again save water. It took an impending crisis for me to become more “mindful” about water usage. And I am sure that millions of Californians are also now becoming more mindful.

Perhaps the biggest problem for Hetch Hetchy’s restoration—and looking at the bigger picture of how we move and use water in California—is that, it most years, the systems function fairly smoothly. We become complacent, take the water for granted. We turn on the tap and water flows, we don’t have rationing, farmers sow and reap, and, in some years, even the fish may flourish. (But, of course, fish don’t vote. And Rep. Nunes thinks they are “stupid” anyway.) California’s incredibly-complex Water Wars never die out, but they are cold wars in many years. Hotter wars are more apt to erupt in drought years.

The crisis of the drought seems to have been wasted by many of our political leaders, at least so far. Their proffered solutions sound distinctly 20th Century—a century of building many massive dams—even 14 years into a 21st Century that might be able to use less cement, and more technology and science, to get water to California’s 38 million people.

But, among citizens at large, more and more people are thinking about water. Even if our first thoughts—following the lead of our political leaders—are sometimes superficial, provincial, greedy, or even flying in the face of science, this thinking has to be a good thing. Because we are, at least, thinking about providing water to a huge population that mostly lives in semi-desert areas. We are not merely taking this absolute necessity for human life for granted, like we usually do.

There is a “Silver Linings Playbook” (pardon the theft of the phrase) for California’s drought crisis. It is that the longer it goes on, the more we will think about water. (And if tree-ring-reading scientists are correct that the prior century of maximal dam-construction was an exceptionally wet one, unlikely to be repeated in this century, we may be in for quite a few more drought years.) As the discussion deepens, almost everything can be “on the [water] table.”

California is home to Silicon Valley and the biggest center of venture-capital on Earth. Might not the local water crisis already have some of these brilliant thinkers and daring investors thinking about innovations in water? And the longer the crisis continues, won’t even more of them think about it?

(Personally, I like the concept of double piping, so we don’t water the farm or garden, or flush the toilet, with precious drinking water. The plumbing construction would also provide many jobs that could not be out-sourced. But there are so many possibilities, some already working that could be expanded, some waiting to start, some yet to be imagined.)

Of California’s 10 biggest cities, 6 are on the Pacific or on San Francisco Bay, including the 4 biggest. Our coastline on the Pacific Ocean is over 800 miles long and most Californians live fairly near all that saltwater. Recently I read that Israel—in a part of the world that is much more of a natural desert than most of California—has been desalinating water for many decades. On February 16, 2014, Seth Siegel wrote in the New York Times that:

More than half of Israel’s drinking water—purer, cleaner and less salty than natural sources—now comes from seawater …. Israel’s self-sufficiency in water goes beyond irrigation, drilling, desalination and reclaimed water. It is also dependent on a sophisticated legal and regulatory structure, market mechanisms, robust public education, an obsession with fixing leaks and efforts to catch rainwater and reduce evaporation, among many other tools. Natural plant-breeding methods have raised crop yields with salty, brackish water of the kind … thought of as worthless …. Israel has transformed water from a struggle with nature to an economic input: You can get all you want if you plan and pay for it.

Clearly most of our polarized and fractious political system is not fully ready to cooperate and “plan and pay for it” at the moment (though the California water bonds are clearly a step in the right direction). But if the water crisis continues or recurs, might not sweet reason someday start to prevail?

Can the Voices for Hetch Hetchy Valley Be Heard Amidst the Shouting of a Drought Crisis?

Surely Hetch Hetchy, right now, is not on many people’s agenda. (Certainly not among elected officials.) Among Californians the bigger water picture is paramount. But, as we think about changing big-picture water policy, everything can be discussed. Yes, even taking down what would be the biggest U.S. dam to be decommissioned to date.

It will not be easy, but people who feel passionate about restoring Hetch Hetchy Valley can break through into the big-picture discussion. After all, of thousands of American dams, only one major dam is in a National Park.

And Hetch Hetchy, over recent decades, has the big advantage of not being a strictly partisan issue. It has been supported by Republicans and Democrats, conservatives and liberals—just not enough of them. So bipartisan support is possible.

Most important is that only one California dam-removal plan has such a big potential constituency. It can be found among people in little towns, cities, counties, and water districts, on farms and fishing boats, in every U.S. state, nationwide, and probably in every single country worldwide. That potential constituency is firmly based on the tens of millions of people who have visited Yosemite and who love Yosemite. Even if they have not seen Hetch Hetchy, if they learn that there’s a Valley anywhere near the equal of Yosemite Valley’s majesty, and it is even within the Park, they might be interested in recovering it.

Almost undoubtedly a higher percentage of Californians know the name Hetch Hetchy than in any other state or country. It’s about proximity. State residents are more likely to have visited Yosemite or, at least, heard about Hetch Hetchy.

Still, I think it’s fair to say that, even in the state in which Yosemite is located, most people probably do not even know the name of Hetch Hetchy. And, among those who do, probably more think of Hetch Hetchy as a water system than as a majestic and inundated Valley in the National Park. Among people who live in other states or countries—and are less likely to have visited the Park—the percentage of people who even know the name is probably in fairly-low single digits.

A majority is probably not necessary to restore the Valley. We have seen countless instances where an impassioned minority has been able to effect political change (for good, ill, or mixed results). But certainly the movement will need to “spread the word” to far more people. As it is, probably a higher percentage of Americans were aware of Hetch Hetchy a century ago, when the Raker Act was being debated, than are today. But probably more know it today than, say, 10 years ago.

The movement to “spread the word” about Hetch Hetchy is not without valuable assets. Major newspapers, from Sacramento to Los Angeles to New York, are sympathetic to restoring the Valley. Environmental and wilderness groups of all sorts favor it (and some of the others, who did not take a position on Prop F, might be won over). Water education groups also can teach people about the Valley. National Parks support groups are a natural ally.

Heyday Books of Berkeley has recently published a beautiful book, Hetch Hetchy: Undoing a Great American Mistake, by Ken Brower. We, at Sierra College, are doing our small part in producing this Hetch Hetchy journal. People play the DVD of Ken Burns’ 2009 documentary on our National Parks and show it to their friends. Thousands of people see Lee Stetson’s plays on John Muir and Hetch Hetchy. The Restore Hetch Hetchy organization—led by its dynamic new Executive Director Spreck Rosekrans, a renowned water-policy expert—organizes, educates, networks, advocates, and runs an informative website.

For the past few years, Restore Hetch Hetchy has also led backpacking and day-hike trips through the Hetch Hetchy back-country. This probably has an extremely high success rate for their cause. Though yet not a mass movement, actually going to the Valley itself is almost certain to make a person a Hetch Hetchy partisan.

In this they are following in the footsteps of John Muir and others who fought to save Sierra wilderness. Among those was David Brower (author Ken Brower’s father). David Brower was Executive Director of the Sierra Club for 17 years and, in 1969, he also founded the environmental group Friends of the Earth.

In 2010, my friend Gary Noy and I co-edited The Illuminated Landscape: a Sierra Nevada Anthology, jointly published by Sierra College Press, Santa Clara University, and Heyday Books. We were both intent on including some writing by David Brower, a man we revered, and one who did so much to save the Sierra Nevada. In our excerpt from his Gentle Wilderness, David Brower wrote that, among many other things:

[John Muir] wrote and talked and led with exuberant energy—with the same energy that took him through his favorite forests, among the alpine gardens he loved, and on up so many of the Sierra peaks. He also founded the Sierra Club “to explore, enjoy, and render accessible” the mountain range it was named after …. One of his ideas for rendering the Sierra accessible was a program of summer wilderness outings which he and William E. Colby initiated in 1901. Too many of the places he loved were being lost because too few people knew about them …. The giant sequoias were being logged for grape stakes. Hetch Hetchy itself was to be dammed …. People must see for themselves, appraise the danger to the spot on the spot. Informed devoted defense would ensue.

And, while the battle to inundate the Hetch Hetchy Valley was lost long ago, a huge number of battles to preserve nature and wilderness were won by preservationists who had “seen for themselves” the places they were fighting to save. Such victories have been won over and over again, for more than a century. Surely this can also apply to Hetch Hetchy restoration, even more than 100 years after the Raker Act battle was lost.

Some Political “Miracles” Take a Long Time, Some a Short Time, But Political “Miracles” Do Occur

When my Mom was born in 1914, our country was in the middle of what you might call a 28-year “Drought of Black People in Congress.” Our country, as a whole, was racist to an extent that is hard, for most of us alive in America today, to even imagine. Emboldened by an 1896 Supreme Court decision that made racial segregation legal, Southern states, where most African Americans then lived, were depriving them of the vote. (And women, of any color, could not vote yet.) While 21 black people, all Southern Republicans, had been elected to Congress in the late 1800s, from 1901 until 1928 not a single black person served in Congress, although they were a majority in quite a few Districts. When I was born in 1943, there was just one black person, Rep. William Dawson, a Chicago Democrat, in a Congress of 535 people (counting both House and Senate).

By the time my daughter Cedra was born, in 1972, the Supreme Court had outlawed some forms of segregation, there had been mass “sit-ins” and marches for desegregation, and the mid-1960s Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act had been voted into law. So there were 13 black people in the House and one in the Senate, including our own Congressman Ron Dellums, representing Oakland. Later in 1972, with the Voting Rights Act taking hold despite intense resistance, the South elected its first two black people to Congress in the 20th Century. (They were Andrew Young, a man from Georgia, and a woman from Texas, Barbara Jordan.)

When my youngest granddaughter Emma was born in late November 2012, there were 43 black men and women—roughly their share of the population—serving in the House (along with dozens of other non-white people from several different ethnicities). And a few weeks before Emma’s birth, the nation’s first black president had been elected to his second term.

In the 98 years between my Mom’s birth and Emma’s birth, a political miracle had occurred.

When Harvey Milk was assassinated in 1978, he was an exception as an openly-gay elected official, voted in as a San Francisco County Supervisor. By 2011, Gay Politics reported that 48 out of the 50 states in America had one or more openly-gay or lesbian elected officials. That political miracle happened faster.

Mono Lake might be a more relevant political miracle for the issue of Hetch Hetchy restoration. The natural habitats being disputed are both bodies of water in the Sierra Nevada. And those habitats were being disturbed by the ways big California cities, hundreds of miles away, were dealing with the High Sierra water whose rights, by hook or by crook, they had obtained long ago. In one case, they were inundating a scenic valley and in the other they were draining an ancient, unique lake.

Now—after decades of drawing down the Lake to dangerous levels by diverting streams feeding it—Los Angeles’ Department of Water and Power is slowly raising the level of Mono Lake. It is one of the oldest lakes in North America and an important bird sanctuary and nesting grounds, visited by nearly two million migratory birds a year. And it was saved in only a few decades.

Mono Lake—a very-salty lake far from major population centers and perhaps not classically beautiful (though I like it a lot)—had an infinitesimal potential constituency compared to those who know the spectacular Yosemite National Park. Although near Yosemite’s eastern border in the high-desert shadow of the Eastern Sierra, I doubt that even 2% of Californians have ever seen this big, haunting, mysterious lake within their borders.

To my mind, Mono Lake is unforgettable, deeply-peaceful, and compelling. The otherworldly tufa towers are unique and oddly majestic. Its unusual ecosystem, based on brine shrimp, alkali flies, and the many varieties of birds who eat them, is a wonder. I have shared Mono Lake often with friends and family, and sung its praises, ever since I first saw it 45 years ago. And my wife Debbie and I—as well as some of my friends and colleagues contributing to this journal—were big supporters of efforts to save what, for us, is a very special place on Earth.

(Mono Lake is in Mary Austin’s “land of little rain” where the steep, dramatic side of the high Sierra meets the high plateau and you can see “forever.” I recommend a leisurely trip with many stops on U.S. 395, between Reno and Lone Pine, if you have not yet visited the many jaw-dropping attractions of the Sierra’s East Side and Mono Lake itself.)

Still, Mono Lake can count only a tiny percentage of people who “have seen for themselves.” And yet a small group of activists formed the Save Mono Lake Committee. Then they built support among local people, among visitors, among Southern Californians, and nationwide, eventually forcing the nation’s 2nd biggest city to replenish Mono Lake. David v. Goliath indeed.

Many Paths and Much Hard Work in Making a Political Miracle

For Hetch Hetchy, what will be the first breakthrough? Like these political struggles, and many others, it will not be one thing, but many things, that lead to the political miracle. It may be a legal case. It may be legislation. It may be an executive or administrative action. Politicians—given a set of new circumstances or crisis or inspiration—may change long-held views. Politicians may retire. Not to be ageist, as I am fairly old myself, but “California’s Big 3 in D.C.,” Boxer, Pelosi, and Feinstein, are respectively 74, 74, and 81 years old. On the other hand, Rep. Nunes, who also seems to have a very-safe seat, is only 41. (In late-breaking news, Senator Boxer has announced that she will not run for re-election in 2016.)

Maybe Restore Hetch Hetchy goes back to the San Francisco “home court” for another go-around and they increase their percentage, maybe even win. Maybe they influence future Representatives, a Speaker, a Leader, or future Senators from California. Maybe a future President. Maybe they win a court case. Certainly they build a national, even international, constituency.

They also encourage people to visit Hetch Hetchy. Even merely looking up-river [or currently up-reservoir] from the dam itself can give one an idea of the Valley’s grandeur. Walking in along masses of imposing granite, pausing for refreshment by some of the impressive waterfalls, or hiking into the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne will be even more persuasive. The ultra-hardy can even back-pack west from Tuolumne Meadows—at 8,600 feet, near Tioga Pass, and not too far from Mono Lake in the eastern end of the Park—down along the Tuolumne River to Hetch Hetchy. They try to get more people to “see for themselves.”

Cultural and even athletic figures can be important in creating political miracles. I think back to the days when racial segregation was being fought, especially in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. I have long felt that, say, white people who admired Bill Russell or Willie Mays or Aretha Franklin or Sidney Poitier or James Baldwin or Toni Morrison might, eventually, find it harder to decide that their fellow African Americans should be forcibly kept from voting or eating at a lunch counter.

Perhaps “The Cosby Show,” “The Jeffersons,” “Good Times,” “Sanford and Son,” and “A Different World” helped, in some small respects, to eventually pave the way for a black president. I would guess that more-recent TV shows like “Will and Grace” and “Modern Family” and “Ellen” had some part in growing acceptance of gays and lesbians.

Likewise, Marc Reisner’s books about Western water policy, like Cadillac Desert and A Dangerous Place, helped set the intellectual and information parameters for the Save Mono Lake Committee to succeed. So did the movie “Chinatown,” by suggesting to people in Southern California that their water might have been obtained by less-than-honorable means. Reisner’s books and the film, by the way, are also applicable to Hetch Hetchy.

In California we not only have Silicon Valley, the greatest public university system in the world, and a widespread, thriving community-college system. We also have Hollywood. And a lot of Hollywood people “in the industry” have probably seen Yosemite, maybe a few have even seen Hetch Hetchy.

Perhaps somebody who loves Yosemite will do a major big-budget movie about John Muir. It’s a great story. You have his strict, very-religious upbringing in Scotland and on the farm in the woods of Wisconsin. You have young Muir’s 1,000 mile walk to the Gulf of Mexico, living in a rustic cabin at the foot of Yosemite Falls when few people knew anything about Yosemite, and Muir’s camping trip with Teddy Roosevelt that did so much to make Yosemite a lasting National Park. There’s his beautifully-preserved house and ranch in Martinez, Muir’s warm family life there, his writing and his activism. For adventure, Muir rides out the storm high in a tree [for fun!] near the Yuba River and you re-live a perilous day on an Alaskan glacier with John Muir and the “wee dog” Stickeen. Armed with only bread and tea, you “climb every mountain” with Muir.

The visuals—mostly in the Sierra Nevada, but also from Alaska to Florida—would be stunning. There might even be a 3-D version. At the end you can roll scenes from all the National Parks that Muir, even posthumously, helped establish.

A teenage heart-throb can play young Muir, maybe Brad Pitt can play middle-aged Muir, and I know a politically-involved actor in Mariposa County who could play the mature Muir during the Hetch Hetchy battle.

At any rate, that’s one of my personal “pipe dreams.” Do you know any Hollywood producers? I offer my “pitch” free of charge. (But, if they insist on paying me, I won’t argue.)

Hetch Hetchy is a wonderful word to spread, but many people and a lot of persistence are needed to spread it further.

It seems likely to me that the Hetch Hetchy Valley will one day be one of those political miracles. The issue has been far more prevalent in the last 10 years than in any of the decades since the dam was completed and water started to flow from the reservoir in the early 1930s. The Hetch Hetchy Valley is not going away, it’s there just below the reservoir’s surface. And the little band of activists is not going away either.

The Hetch Hetchy Valley is in a National Park, for goodness sake! And it’s not just in any old National Park. It is in Yosemite National Park! Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt, two of our greatest presidents, did a lot to save Yosemite. It is the place where John Muir lived as a young man. It is the unforgettable Park that millions of people visit every year.

One day people will again walk—like the Native Californians and Muir and other lovers of “the wild places” did—on the Hetch Hetchy Valley floor. I have seen so much progress in my lifetime that I can’t believe that—with all our human ingenuity—we will not be able to let the River flow free, at least within the Park. (And probably also most of the way through the Stanislaus National Forest to the west). Surely we can store the Tuolumne’s valuable waters much further downstream, outside what should be a sacred National Park.

I can’t tell you exactly when it will happen, but I am certain that it will. I know my nature-loving, Yosemite-loving grown-up daughters will walk on the Hetch Hetchy Valley floor. I know my grandkids will too. And I hope I get to join them.

Images Credits

- Diane Feinstein official photo

- Lee Stetson by permission