A Naturalist's Transect along the I-80 Corridor in California:

Rockin to Donner Pass

J. L. Medeiros

Professor Emeritus, Biological Sciences

This story parallels a similar geological transect written by Professor Richard Hilton. Dick and I have been leading student trips up and down the I-80 corridor for decades. Our wanderings along this interstate, with side trips on the old Lincoln Highway (Hwy 40) have been both instructive and immensely pleasurable.

Interstate highways enable travelers to see much of America in a relatively short period of time and Interstate 80 provides a brief but splendid snapshot of the physical and biological stuff that makes the Sierra Nevada what it is. Those that think these mountains are a solid core of granite will be surprised that many other rocks and soils dominate the landscape until nearly 6,000 feet in elevation (at this latitude). Also, those that think the Sierra is made up of "just pine trees" will be astounded by its tremendous diversity of non-pine conifers and myriad broadleaf trees.

In roughly 100 east-to-west miles the traveler can move through hundreds of millions of years of past geological activity and through numerous life-zones, plant communities, and ecosystems. This is truly a place where the journey is often more valuable than the destination. For many, it is the main east-west commercial artery (attest by the number of windshields cracked by rocks delivered by 18-wheel trucks en route to distant destinations). For others it’s the quickest way to winter skiing (oops, that is, snowboarding now), gambling, and the largest, most strikingly beautiful mountain lake in the Sierra, Lake Tahoe.

Introduction

This review of the plant communities and associated biota along I-80 begins among the lower, nearly-flat foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Here, at the edge of the Sacramento Valley, the northern lobe of California's Great Valley, enough precipitation falls to support the formation of shrubs and woodland trees. Below Rocklin, a busy capitol region has been literally transformed by commercial and municipal sprawl.

Once-expansive grasslands, wetlands, and vernal pools have been obliterated to make way for people and their relentless busywork. The nearby American River has been extensively dammed; levees constructed to reduce the threat of floods – all to store and manage precious water for California's cities and agribusiness. The once broad and towering riparian woodlands of oaks, sycamores, walnuts, willows, and alders are now restricted to narrow strips of forests – small relict forests living between the river and the levees.

Water is a key component in the flourishing of all life. For plants, it is instrumental to their size and distribution. In most of California, with its Mediterranean climate, the water comes during cool, wet winters that alternate with hot, dry summers. This relatively uncommon climate pattern dramatically affects the ecology of the entire Sierra region. During winter storms, parcels of moisture-laden air masses are pushed eastward over the Pacific Ocean and onto the state. The parcels travel over the landscape, lifted upwards by the mountain topography of the Coast Ranges and the Sierra Nevada. Known as orographic precipitation, this activity creates wetter situations on west-facing slopes and semi-arid rain-shadow ecosystems on east-facing slopes.

As a rule of thumb, the higher the air parcel is forced, the more precipitation it will generate. As a result, west-slope woodlands and forests are replaced by drier grassland-savanna and scrub on the east-facing slopes of the Coast Ranges. Commensurately in the Sierra, as the traveler moves upwards in elevation, the grasslands of the valley transition into woodlands in the foothills. Such woodlands are rather openly vegetated by various oak species, some Foothill pine, and a variety of shrubs.

Just enough additional rainfall in these foothills enables larger, woodier species of plants (shrubs and trees) to replace the grass-dominated communities of the valley floor below.

As we continue eastward and upwards in elevation, this trend of increased precipitation becomes the keystone physical component that influences the pageant of arboreal species that will dominate the landscape and entertain curious passersby. With altitude, the foothill woodlands give way to lush, dense mixed-conifer forests. With increased elevation, these forests will transition into tall, but more open ecosystems of yet different species.

Even higher up, the altitude, winds, and heavy snow-loads will influence the types and forms of sub-alpine forest species. And, above this, in the "land above the trees," lofty but diminutive ecosystems known as alpine tundra, annually covered under a winter blanket of snow, will provide the summer hiker unending floral and landscape beauty. Where continuous or patchy snow and ice persist, the craggy nival (snow) zone exists – home for few year-round species.

How It Got This Way and the Simplified Story

Professor Hilton aptly describes the wandering of massive continents on Earth's crust over time. He discusses basic concepts of the science of plate tectonics and how North America, California, and eventually the Sierra Nevada waltz to the globe's slow rhythms. In addition to the physical movement of massive crustal plates, the dimension of time itself must be incorporated into the complete understanding of how forests and other Sierra ecosystems came to be.

Hilton's abbreviated and simplified story discusses ancient times and the whereabouts of rivers, mountains, volcanoes, glaciers, and other geophysical features that have influenced the present shape and position of the Sierra. As such physical features went about their mechanical meanderings, life simultaneously conducted its very own elegant (and yet unfinished) symphony. Simpler organisms evolved into others that were more complex – more adapted and competitive in their changing world.

Plants and animals that had long before emerged from shallow seas began colonizing the continuously moving land masses. Modern-day descendents of these early primitive types still cling, mostly tenaciously, to the same land masses where they first washed ashore, or where they evolved from earlier ancestors.

Others are descendents of immigrants, coming from distant lands, carried by wind currents, or traveling here on the feet of birds, stuck to the fur of mammals, or even as partially digested seeds in the gut of an unsuspecting transporter.

As a result, the Sierra that we see today is but a snapshot, and only a recent one at that, of life's continuing evolution in North America. Our photo album of North America (if we had a time machine and camera) would include Paleozoic forests of giant horsetails, ferns, and lycopods; bizarre arthropods combing the ground and giant dragonflies soaring overhead.

While the present Sierra region was still long in coming, by the Mesozoic most of these earlier more primitive plants would be replaced by cycads, ginkgos, and early conifers – many of which spread westward and occupied the newly accreted land masses. Reptiles and birds would rule land, water, and sky while diminutive proto-mammals scurried in the leaf litter. It would not be until the Cenozoic that flowering plants would diversify to later dominate the terrestrial landscape with broadleaf trees and shrubs, along with showy blooms and fleshy fruit-producing plants. Insects, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals would continue to diversify and evolve to occupy new lands and ecological niches.

Thusly, the Sierra Nevada is an intricate quilt that continues to be rewoven and redesigned. The lush and towering forests that we see today were not always present. Over time various species colonized the continuously-evolving Sierra. Pioneering species were replaced with stage after stage of others that could out-compete their predecessors. The mountains rose while also being eroded. Climate repeatedly shifted from warm to cold, from wet to dry—over and over again. New ecosystems arose as a result of dynamic physical changes. Climate, fire and soil development contributed significantly to these changes. Immigrant species moved in and others moved away. Glaciers waxed and waned, sculpting and shaping the Sierra. At the end of the last major ice age, more than 10,000 years ago, humans showed up – and the Sierra acquired it's most powerful and influential evolutionary agent.

Road Log

Sierra College's Rocklin campus was built alongside Secret Ravine, a tributary of Dry Creek. Originating in the Loomis Basin, Secret Ravine joins Clover Valley Creek, Miners Ravine, and many others in the Roseville area. Dry Creek then gathers volume and sediment until the entire watershed (about 100 square miles) terminates alongside the American River in Sacramento. Not far away, the much larger American River watershed collects 1900 square miles of Sierran snow and rainfall, but remains separate from Dry Creek until their confluence at the Sacramento River.

Surrounded by a rapidly developing western Placer County, Secret Ravine remains one of very few undammed foothill streams where anadromous fish like Chinook salmon and Steelhead trout continue to make spawning migrations from the sea. Numerous organizations like the Dry Creek Conservancy have worked very hard to restore and protect this special and threatened creek (www.drycreekconservancy.org).

The woods around Sierra College and Rocklin are partly natural (native) but are mostly greatly modified. The most recent natural vegetation, prior to significant human influence, was a combination of oak and pine woodlands, savanna (open oak forests within grasslands), open grasslands, and riparian (streamside) forests. Since then, a great deal of ecosystem conversion has occurred due to intensive human activity.

Mining, quarrying, and railroad activity disrupted huge tracts of land. More recently ranchers, farmers, and land-developers, have cleared much of the remaining original vegetation and replaced it with non-native crops and trees (followed by alien insects, birds, and mammals.) Despite hundreds of years of intense alterations, native oaks (Interior live oak and Blue oak) and Foothill pines persevere in the regional landscape.

Once called Digger pine, the Foothill pine is the only native pine in the low elevation Sierra. With appropriate respect to the local Native American peoples [once called Digger Indians] the former vernacular name is now considered offensive and disparaging. Many other "common" names for California species have also been changed and corrected as we learn and understand more.

Alongside streams like Secret Ravine, White alders and Valley oaks, as well as numerous species of willow line the banks. These riparian (bank-side) forests can be tall and lush. In many cases they have been spared annihilation because they lie within the floodplain – where less development occurs (until the invention of the levee). Nearby native grasslands have been plowed and planted with alien grains and food species. Where open grasslands still exist, weedy species of foreign annuals (introduced mostly from the Mediterranean) have largely replaced the perennial bunchgrasses and native wildflowers.

Much of the foothill woodland and oak savanna communities still exists, but nearly all that remains is endangered and threatened by urban sprawl. These irreplaceable woodlands are destroyed for subdivisions, malls and commercial developments. Nowhere can these unique Sierra Nevada plant communities be reconstructed but organizations such as Placer Land Trust are working hard to purchase, put into conservation easement, or otherwise protect some of what remains.

Of all of the Sierra's ecosystems, these lower elevation woodlands are the most biologically rich and diverse. Yet, less than 5% of the foothills are in public ownership or are protected in any way. Every acre that is preserved now and in the future will count significantly for the region's total ecological health. (See Placer Land Trust at www.placerlandtrust.org)

Driving eastward up I-80 the traveler may be confused by trees and landscapes that don't seem to fit the classic definitions of oak woodland or savanna. This is due to the fact that homesteaders and recent homeowners often prefer different trees in their landscapes.

Out the window of your car you might view distant fruit orchards on the hillsides, tall palm trees that line roadways, or "Dr. Seuss Trees" (Deodar cedars) that cluster around many off-ramps. Deodar cedars, with their nodding tops and wispy branches, are sturdy conifers native to the Himalaya Mountains. Their drought and high-temperature tolerance makes them perfect choices for the hot and dry foothills; state highway landscapers plant them by the thousands along highways and intersections – I have nicknamed them "CalTrans pine." They are true cedars; we have no true cedars in the New World – all of our "cedars" are actually members of the cypress family.

Many other introduced tree species have been used for color and beauty in the California landscape – from the brilliant fall colors of the Chinese pistachios on our Rocklin campus to the many species of palms imported from around the world. If you're looking for the "natural" Sierra forests, you'll have to drive a bit farther up the hill.

Stop #1

Overlooking the Loomis Basin you will be able to scan this crazy-quilt of both natural and introduced vegetation. Western Placer County was once a major fruit producer and a valiant effort exists to resurrect and protect this important local economy (See www.PlacerGrown.org).

Lots of native foothill species can be spotted, especially where there appears to be little disturbance (no homes, irrigated pastures, orchards, etc.).

The basin is greener than it should be – especially in the summer and fall months. Irrigation, while benefiting the farmer, the pasture, or the landscaped home, creates a much greener year-round environment. Prior to the advent of irrigation, natural vegetation had to tolerate heat and prolonged drought. Various strategies evolved, from dormancy to tolerance to migration – and the foothills regularly and quietly survived the Mediterranean climate pattern (short, cool and moist winters and long, hot, dry summers).

But irrigation and other human constructs that have benefited us have also negatively affected the natural ecosystems. Too much moisture encourages fungal disease in native oaks and many other woody species. Thousands of oaks have been killed by lawns alone and golf courses continue to make the same mistake.

Once intermittent, foothill streams are now year-round waterways. Many species of fish and other aquatic species, dependent upon the seasonal weather patterns, both tolerate and require the alternating wet and dry periods for their natural cycles. Today, these perennial streams favor introduced species like perch, bluegill, and bullfrog – all at the expense of native fauna. Hundreds of native plants and animals have been extirpated (locally eliminated) and replaced with alien species (blackberries, periwinkle, etc.) that most consider "natural" along streams in the wild. In open grasslands, other introduced weeds like Yellow star-thistle overrun the native vegetation.

Stop #2

Drive along Indian Hill Road and you're riding upon ancient volcanic mud-flows, rocks, and boulders carried downwards for the past tens of millions of years.

Notice the distinct differences in vegetational structure as you look southwest into the Sacramento Valley. The "hill" upon which you drive is a conglomeration of ancient and resistant rocks that erode much more slowly than the granitic rocks of the Loomis Basin below.

While on this ridge you'll enjoy the same classic oak savanna while seeing more human influence (orchards, pastures, ranchettes, etc.) and ample plantings of non-native and ornamental trees along the slopes below. When the "hill" is crested (nearer to Auburn-Folsom Road) imagine the enormous efforts required to level and prepare the sites for homes and other buildings. Heavy-duty equipment is required to break through the concrete-like structure of these volcanic mud-flows.

Turning left (north) along Auburn-Folsom Road you'll enter the town of Auburn. While many old oaks remain along your route, you see more ornamental trees (adding lots of fall color) planted in Auburn yards. A detour (to the right) at Pacific Avenue will take you to the old "Auburn Dam Overlook" where a broad view of the American River Canyon is available.

The story of the never-completed Auburn Dam is a piece of Sierran history in itself. While the proposed two million acre-foot reservoir would certainly have added to flood protection of metropolitan regions below, it would also have been the death knell to 40 linear miles of flowing river (North and Middle forks) and more than 10,000 acres of exuberant foothill woodland ecosystems. This area has been temporarily transferred to the California State Department of Parks and Recreation and is locally managed by the Auburn State Recreation Area.

(See PARC / Protect American River Canyons at www.parc-auburn.org)

(See American River Canyon Keepers at www.psyber.com/~asra/asrack.htm)

While Foothill pines, Blue oaks, and Interior live oaks dominate the arboreal landscape, this is also the Sierran zone where California buckeye, Western redbud, manzanita, and Buckbrush flourish. These large drought-tolerant shrubs (to tree-sized in the buckeyes) provide showy floral color in late winter and early spring.

Stop #3

In Auburn (approximately 1250' elevation), slightly increased annual rainfall and cooler average temperatures initiate an observed variation in vegetation. While Foothill pines still abound, the occasional Ponderosa pine can be spotted. Additionally, Black oaks join the woodlands along cooler slopes and moister soils.

By the time you get to Clipper Gap and Applegate, the foothill woodlands have nearly been replaced by forests of Ponderosa pines and Black oaks. However, you might also notice the effects of "aspect" as you look left and right (north and south) along the interstate. "Aspect" refers to the direction that a slope is facing. At our latitude (roughly 39 degrees north of the Equator) the sun tracks only in our southern sky. Consequently, south-facing slopes get warmer than north-facing slopes. As south-facing slopes heat up, they dry out faster and tend to have plants that reflect warmer and drier soils; it is the opposite situation for north-facing slopes.

Where more foothill pines and live oaks can be spotted on the south-facing side of the freeway, you'll tend to see more Ponderosa pine and Black oak forests on the north-facing side. Once you advance up the hill, the cooler, moister environment will enable a dense cover of Ponderosa pine and Black oak, almost regardless of aspect.

Ponderosa pine, with its fist-sized prickly cones, was named for its weighty bulk. This is the most widely distributed conifer in North America. Before their felling by loggers, miners, and railroad builders, there were Ponderosas that exceeded eight feet in diameter (today it's rare to find one over four feet wide).

Black oaks are a tall and deciduous tree having large, deeply lobed leaves. Since there are other black oak species in the west, we refer to ours as California black oak. It is a large and beautiful tree that is still used (mostly up north) as a hardwood-providing species. With sustainable forest practices, California's tree species can be managed to provide human resources (fiber, wood, recreation, etc.), critical habitat for plants and animals, and ecological services (watershed maintenance, soil stability, oxygen production, carbon dioxide sequestration, air purification, etc.).

Upon the weathered sediments and metamorphic rocks of this zone exist some of the richest and most productive Sierra forest ecosystems. While Ponderosa pine and Black oak dominate, you'll now start seeing numerous other tree species flourishing in this "lower yellow pine" complex. Douglas-fir is common here, as is also the Incense cedar. These two conifers are both misnamed. Douglas-fir is not a true fir (we'll being to see true firs as we increase in altitude) and Incense cedar is not a true cedar. Confusing? Let me explain.

Douglas-fir is our only remaining relative of a group of Asian conifers that once grew in North America. They have thin, flat needles that resemble those of true firs, but their cones are quite different. True firs (we'll see White and Red firs on our tour) have robust, barrel-shaped cones that grow upwards from their branches.

The Douglas-fir of North America has more fragile, light-weight cones that dangle, pendulously, from their twigs.

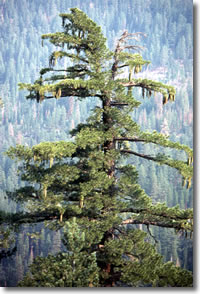

Between each cone scale is found a slender tail-like bract that extends beyond the seed scales. Structurally, young Douglas-firs seem to welcome the filtered sunlight with "open arms"; their young branches extended upwards at an acute angle to the trunk. In contrast, older trees have long and wispy branches extending from their stout trunks. They appear almost "furry" with dense but tiny needles as opposed to the obvious longer and pricklier needles that grow from the branchlets of pines.

Douglas-fir is highly-prized and is eagerly sought for its straight, strong, and white wood. While many Douglas-fir trees fill the surrounding forests, their stature and number are but a small representation of the millions of much bigger specimens that were ruthlessly extracted from the virgin Sierra. Finding a big Douglas-fir requires visiting an old growth or ancient forest that has not yet been cut over (believe it or not, we have some in Placer County).

As mentioned earlier, North America's "cedars" are actually members of the cypress family. The famed "cedars" of the Pacific Northwest (Port Orford, Alaska-cedar, and Western Redcedar) are members of this same conifer family. Ours were probably misnamed as their wood is fine-grained, reddish in color, and fragrant like the true cedars of the Old World. The Lebanese cedar (Eurasia) was nearly extincted for temple-building while the Atlas cedars (North Africa) were deforested for fuel and heat.

The Deodar cedar is from the Himalaya. Deodars can be found often along the I-80 corridor – planted as ornamentals or landscape trees. Our own native Incense-cedar is a prolific tree species. Unwanted by the early lumberjacks (their wood was pocked with "worm holes") they were often left standing in clearcuts. There they proliferated by seed with significantly reduced competition from other (removed) tree species.

Today, the suppression of fire continues to give Incense-cedar seedlings a competitive edge. Once used for railway ties, beams, and shingles this cinnamon-barked conifer is pervasive in the mid-Sierra but less common in the Cascades or the Coast Ranges. If you enjoy the smell of the wood pencil, you can thank the Incense-cedar for its contribution.

Joining the list of tree species at this elevation are Sugar pine, White fir, Mountain dogwood, and Bigleaf maple. Sugar pine is the world's tallest (over 250') and largest pine. John Muir referred to it as "the noblest pine" of the Sierra. Its long cones (up to 24") can be seen dangling from the tips of its long, slender branches.

White fir (a true fir) has shorter, flattened needles growing from branches that appear to be stacked in horizontal layers or whorls. A pinch and twist of a White fir needle will provide a very aromatic fragrance – perhaps reminding you of Christmas. Old trees have ashy-gray bark furrowed irregularly in a thick protective layer. At lower elevations (below 8000 feet) the White fir is our only true fir. At higher elevations the White fir will mingle with its subalpine cousin, the Red fir.

A few broadleaf tree species provide variety in shape and color in these same woods. In spring, what appears like robust blooms in the Mountain dogwood are actually creamy white bracts that surround small flower clusters. Dogwood leaves may turn brilliant red in the fall. The large leaves of Bigleaf maple add to fall color in this forest as well.

Together, these and the other aforementioned trees join to make up the mixed-conifer forest – the largest zone of vegetation in the Sierra. Broad in elevational range and lengthy in latitude, the mixed-conifer zone occupies millions of acres in the Sierra. While there is a good deal of private land in this zone, most of it is managed by the National Forest Service (NFS – U.S. Department of Agriculture).

In the past, it was from these publicly owned forests that vast amounts of lumber were irresponsibly extracted. Fire suppression, over-harvesting, and ineffective management left most of the mid-elevation Sierra forests severely impacted. Using science and new management techniques there are many efforts to restore these once-flourishing lands. However, politics and economic greed continue complicate these important efforts.

Stop #4: Exit at Gold Run Rest Stop

This newly remodeled rest stop enables you to stretch your legs and take a break. You're now at approximately 3200 feet in elevation and things are a bit different. Most likely you'll experience a cooler temperature than when you began your journey below. It might be hard to imagine this area once being forested with subtropical trees – when gold was being laid down in Eocene river beds. Professor Hilton tells you a bit of California's rich history at this stop; the hydraulic mining that occurred here enables you to actually see the deep, gold-bearing gravel beds in cross section. The story of gold is significant in California's history, both economically and ecologically – and gold fever continues to wreak havoc in the world today, culturally as well as environmentally.

While you're stretching your legs you can try your hand at identifying some of the trees we've been discussing. Just east of the restrooms (toward the Reno direction) you can more closely examine Douglas-fir. Look for its fine and soft needles and especially its characteristic cones (with the "tails" jutting out between each cone scale). If you can't find cones on the tree, scan the ground below the branches. Walk a bit farther east and scan the horizon for Sugar pines. Look for long and elegant branches from which may dangle their famous long cones. Different than other conifers, the upper branches of the Sugar pine can often be as long as lower ones. None of their lateral branches get too thick in diameter, allowing snow to be shed as the flexible branches droop when loaded.

West of the restrooms (towards the Sacramento direction) try to find the Knobcone pine. These hardy natives have slender (and asymmetrical) cones wrapped in tight whorls around their branches. Short-lived, they will not reproduce without fire. In the past, before human fire-suppression efforts began, their life cycles were relatively short, reseeding every dozen or so years after a cleansing fire. With sufficient heat their cones open, releasing their stony seeds. After the fire, with little competition for water, light, and the nutrients released by the flames, they germinate prolifically and their seedlings will compete at first, with only their siblings.

Across the interstate you can clearly observe the gravel beds that Professor Hilton discusses. These ancient soils are naturally acidic and contain elements that inhibit optimal plant growth. Scan the rest stop area and notice that much of the vegetation is dwarfed or reduced in stature. At our next stop you will see this plant-soil relationship even more distinctly.

Exit at Alta, turning right and then an immediate left on Casa Loma Road. Shortly, when you see the railroad bridge, you might park under it for a look at something special. Long ago, when this bridge was built, someone planted four Giant Sequoia trees as sentinels. Today they are large and handsome and three of them have characteristic "middle-age" tops like sharply pointed spires (the fourth has been damaged). You'll see these more clearly when you return to I-80 and head up towards Reno after this side-trip. Don't forget to look for them when you're speeding past and headed up the hill. Giant Sequoias are the largest (volume) tree in the world.

More than 80 groves of "Big Trees" live in the Sierra (mostly in the southern Sierra) between 4000 and 6000 feet elevation. While these four trees were planted here, Placer County has the distinction of having the northernmost wild grove of this very unique tree. A very small grove above the Middle Fork American River includes six living and two fallen sequoias and is protected in a reserve by the Tahoe National Forest. A day trip (past Foresthill and down Mosquito Ridge Road) will take you to this splendid little reserve.

Interestingly, the next grove of Big Trees is 55 miles south (as the Red-tailed hawk flies) at Calaveras Big Trees (another banner destination) on Hwy 4. Contemplate these massive trees and consider the fact that they begin from a seed no larger than the capital letter at the beginning of this sentence. At 90,000 seeds per pound (it takes 200 of them to weigh the same as a paper clip). A single seed can grow into a tree weighing 12 million pounds (450 tons) – equivalent to three Blue whales or 75 elephants!

Backtrack and take the road just before (downstream of) the railroad bridge. Travel across the creek and through a lush mixed-evergreen forest. Dominated by White fir, Ponderosa pine, Incense cedar, Douglas-fir and Black oak, this is an especially good place to find Mountain dogwood and Bigleaf maple. In spring the dogwood flowers are especially elegant and in fall, the leaves of both dogwoods (red) and maples (gold) will make for some great photos.

Stop #5

You'll have no trouble finding Professor Hilton's next spot. After you've driven a few minutes through this lovely forest, you'll come to a large "barren" or treeless area that almost appears as if a fire had recently cleared it. A walk to the precipitous edge will be well worth it as you wander across a lens of serpentine that hinders normal plant growth. In the distance (south) you can see the remarkably flat Sierra that has been tilted and eroded during the past five million years. Where one may imagine the Sierra as a continuous mass of jagged peaks, such features are limited to its lofty crest or reserved for more atypical situations.

If anyone envisions a hike along the John Muir Trail to be a gentle and flat stroll along its most spectacular peaks, they're sadly mistaken. Hiking from north to south in the Sierra requires climbing down deep canyons like you see before you and then scrambling back up the other side – only to do this over and over as you progress. As the Sierra tilted, erosion (by water and glaciation) sculpted these canyons westward and down slope, creating countless east-west trending drainages.

The scrubby serpentine vegetation at this site is responding to high concentrations of magnesium (which inhibits critical calcium uptake) and very low concentrations of nitrogen. Added to the mix are heavier metals like mercury, chromium and nickel. However, that which inhibits certain species often provides opportunities for others. The toxic mix of chemistry in serpentine areas excludes only the intolerant, and this provides competitive opportunity for those that can develop survival strategies. California's extensive serpentine areas have essentially forged a whole suite of serpentine-tolerant plants as well as numerous serpentine-endemic plants. The endemics (numerous onion species, lilies, mustards, and parsleys) are more than tolerant; they're obligated to live on serpentine only.

Buckbrush, the most common shrub here, is serpentine-tolerant – as is the Foothill pine that you'll find if you scan the edge of the barren and Yerba santa, a waxy-leaved medicinal shrub. What is Foothill pine doing here? Obviously, elevation alone is not what keeps it from growing in the mixed-conifer forest. Other competitive factors exclude Foothill pine in the Ponderosa-dominated forest around you. But, when Ponderosa pine is excluded by the chemistry of serpentine, the tolerant Foothill pine finds foothold. Oaks in general are also excluded from serpentine; only one shrubby oak species (Leather oak) is serpentine-tolerant. Serpentine chaparral (shrubby vegetative structure) is common throughout the Sierra at any elevation where the rock type is exposed at the surface.

A walk across the railroad tracks and to the canyon rim will provide a marvelous view up and down the North Fork of the American River. Giant's Gap is downstream to the west. Envision miners hauling supplies up and down this canyon to the river below. Nearby (just east) is a trail down to Euchre Bar (so you thought you were in shape?!) on the river and the lower end of Blue Canyon.

After this Giant's Gap overlook stop you'll backtrack to I-80 and head east again. Don't forget to try to spot the four Big trees (Sequoias) at the railroad bridge when you drive past. As you continue upwards you'll be traveling through this extensive and lush mixed-evergreen forest. Why the term "mixed-evergreen?" Not only are there numerous evergreens (conifers like pines, firs, Douglas-firs, and Incense cedar) but these forests are "mixed" in that they also have broadleaf trees living alongside. Broadleaf trees (oaks, maples, dogwoods, etc.) have broad, flattened leaves that are primarily deciduous (winter dormancy). Broadleaf trees are actually flowering plants (angiosperms) that have blooms, albeit often small or not very showy.

You'll now travel quickly upwards to above 5000 feet elevation where you might notice distinct changes in your surroundings. Depending on the time of year you'll probably notice changes in air temperature – cooler as you ascend. The species composition of the forest remains basically the same but the relative proportions are often altered as you travel upwards. Where Ponderosa pine and Black oak dominated the lower elevations, these upper areas will have more White fir, Sugar pine, and Incense cedar.

There are not many spots to pull over and take in the surroundings but the Blue Canyon and Emigrant Gap turnouts both lead to interesting areas for exploration. As Professor Hilton suggests, be ready to emerge from the more-or-less closed forest and gaze upon views that are more open or sparsely vegetated. Off to the north is Lake Spaulding surrounded by glacier-scoured granite. Here, altitude and substrate play an important part in this distinct physiographic change. As you pass by Yuba Gap you'll see the results of the August 2001 Gap Fire which burned more than 2400 acres. Arguments continue here about what is best to do with both public (Tahoe National Forest) and private property. Should we allow salvage logging? Replant? Replant with which species? Leave nature alone to do her thing?

Stop #6

The Highway 20 intersection is a good place to plant one's feet firmly upon the granite of the Sierra for the first time on this tour. If you exit I-80 here (toward Marysville) you'll wrap around a granite dome that you might want to climb. If you continue under the interstate, past the CalTrans barns (for sand and salt) you'll face another dome near the westbound off ramp. Scaling either dome enables you to stretch again and hunt for some new tree species. Climb up and explore some glacial erratics – boulders transported by glaciers and left stranded at a downhill location.

Here, at approximately 5600 feet elevation, the granite core of the Sierra is boldly exposed – the old metamorphics and sediments that enriched the mixed-coniferous forests are below us – eroded or scoured away by glaciers. A hike up one of these domes will reveal pines that very much resemble Ponderosa, but are different. Here the upper elevation cousin of the Ponderosa is the Jeffrey pine. Also a "yellow pine," it differs in a few ways. The most obvious difference is the size of the cones (much larger than that of the Ponderosa) and the fact that the Jeffrey's cone-prickles turn inward into the mature (open) cones. Take the time to sniff the cracks between the bark plates and smell the fragrance of the Jeffrey pine (butterscotch? vanilla?).

A walk upwards will disclose Black oaks, only much reduced in size and stature. This elevation is roughly the uppermost limit of Black oak at this latitude. Black oaks at lower elevation are stouter and taller. California Black oaks have a broad elevational tolerance. Remember, we first saw them in the Auburn area at 1200 feet elevation and now we view them at nearly 6000 feet. An important Sierran tree, they first form leaves at lower elevations (spring bud break). By the time the leaf buds break at this Hwy 20 site, Auburn's Black oaks are fully leafed out. When fall color first comes to Black oaks, it is first here, at their upper elevational limits. Their fall color proceeds slowly downhill and is last seen, around 1200 feet elevation, 30 to 60 days later. Few Sierran tree species illustrate the effects of altitude more clearly than the California Black oak.

On these exfoliated granite domes you will also find the robust and stately Sierra juniper, a special form (subspecies) of the Western juniper. Also a member of the cypress family, the photosynthetic leaves of Sierra juniper are scale-like rather than needles. Hunt around for this shaggy-barked and small conifer with berry-like cones (no larger than peas). Its contorted shape is the result of heavy snow loads or punishing winter winds. We will continue to see this persistent crag-dweller until high up in the subalpine environments.

As you continue eastward up the hill on I-80 you notice distinctly banded rocks to the left (north). Grey and brown in color, unlike the granite you've just observed, these are quite different rocks. These are vertically tilted sea beds laid down during the dinosaur ages.

Watch for more erratics, perched precariously on ledges by ancient glaciers. Your exit at Cisco will enable you to drive along the South Fork of the Yuba River – a small but beautiful tributary. Pass through Cisco Grove. This relatively large grove of Black cottonwoods (different than the Fremont cottonwood of lower elevations) has been preserved by the Gould Family and the Placer Land Trust. Sixteen acres, on both sides of the river, are protected in perpetuity. As you continue eastward along the road you'll pass the USFS Ranger Station at Big Bend. Excellent historic exhibits and public (flushing!) toilets are available here. It's a great place to pick up some maps and books too.

An old campground at the river here was washed away in the January, 1997 floods.

(http://www.fs.fed.us/r5/tahoe/recreation/big_bend/index.shtml)

Stop #7: Loch Leven trailhead parking area

A little farther east from the Ranger Station and you'll find a parking area with concrete vault toilets. A trail leads from here up to Loch Leven Lakes, a delightful collection of subalpine lakes only about 2 miles away (alright, you have to climb up more than 1000 feet in elevation). The lake's name probably came from Scotland (Loch Leven Castle) or, perhaps, from the same moniker given the German brown trout. Nevertheless these lakes are worth the hike (or snowshoe in winter) and picnic. Don't be surprised when you cross the railroad tracks or the signs for the buried diesel fuel pipelines.

At the trailhead parking lot you'll see plenty of Jeffrey pine (smell the fragrant bark and look for large female cones). Look here also for a short-needled pine with only two needles per cluster (Jeffrey and Ponderosa pines have three longer needles in each cluster). These two-needled conifers are Lodgepole pines. Their cones are no larger than golf balls and are roundish when mature and open. The have tiny bristles on each cone scale instead of the bigger prickles of the Jeffrey and Ponderosa. Lodgepole bark is small-scaled, appearing rather like corn flakes. Lodgepole pine and its close relatives can be found at much lower elevations as one travels northward into the boreal forests of Canada and even into the muskegs of Alaska.

A short stroll up the Loch Leven trail will provide even more species for you to observe. The Sierra's smallest oak (Huckleberry oak) is but shrub-sized and is common here. It looks rather like the nearby manzanita but its leaves are distinctly different. Look closely for tiny acorns either on the plant itself or on the ground below the shrub. This diminutive oak can be found from this elevation upwards to above 10,000 feet – higher than any other oak species in California.

Another small shrub will begin showing up at this elevation and higher. This is Pine-mat manzanita – a dwarf compared to its lower elevation relatives. Both Green-leaf manzanita (large shrub) and Pine-mat manzanita can be found together at this transitional elevation. Higher up, only the Pine-mat species will persist. Keep an eye out here for more Sierra junipers too.

Continuing eastward on this, the historic Lincoln Highway (Hwy 40), you'll cross the South Fork Yuba River and rejoin I-80 East. The viewscape in every direction is filled with forests, but again, the species composition is changing subject to increase in elevation. Black cottonwoods and Quaking aspen dominate the riparian landscape. Red osier (Creek dogwood) lines the banks as well. Away from the water's edge, Lodgepole pine will dominate where Jeffrey pine and Douglas-fir are left behind. Western white pine, a higher-elevation cousin of the Sugar pine will start showing up here. Watch for their long, limber branches – much like Sugar pine. We'll see these more easily at Sugar Bowl.

As you turn off at Soda Springs and again travel along the old Hwy 40, you'll enter an area of complex public and private ownership. This was once part of the same land giveaway that provided the first transcontinental railroad its checkerboard (every other section of land) ownership along the rail's Sierran corridor. Private ownership in this high-country area historically allowed unchecked cabin-building and recreational development. Without contiguous ownership, the US Forest Service is not capable of managing this important ecological area. Sensitive wet meadows and subalpine forests are under constant threat by human activities. Currently, the entire area is threatened by a mega-development more than 3000 acres in size (see www.savedonnersummit.org).

Numerous previous activities have radically disturbed the wetlands (Lake Van Norden) and surrounding area. Current activities of homeowners, road-clearing equipment, numerous downhill ski resorts and the railroad continue to threaten this entire sensitive area. A regional public-private management association comprised of representatives from varied interests would benefit this beautiful area tremendously (like the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency). Along the way you'll pass the historic Claire Tappan Lodge (www.ctl.sierraclub.org) and the Central Sierra Snow Lab (http://research.chance.berkeley.edu/cssl) where remarkable snow records of this area (one of the snowiest of the Sierra) have been kept and analyzed.

You are now in another transitional forest where trees from lower and upper elevations intermix. Jeffrey pine is still present but is less common. Lodgepole pine and Western white pine become more prevalent and here we see our first Red firs. Both Red fir and White fir share this transitional forest. Unless you stop along the road and inspect numerous large fir trees, you'll not be able to tell the difference between Red and White fir – but there are plenty of both in this area. Close inspection requires that you leave your car and walk beneath these big beauties. Remember, both have shorter needles (not bundled like pines) and have barrel-shaped, fist-sized cones that grow upwards from their branches. Looking upwards from the base the long spreading branches will offer a telltale difference – White fir needles lay flatter, almost horizontal to the twigs from which they grow.

An upwards glance into the White fir's canopy gives the beholder a fern-like silhouette to study. Red fir, because its short needles curve upwards quickly from their twigs, appears more snowflake-like in shape when you're staring straight up at the sprays. The real test lies with the bark color on the mature trees. The bark of both is coarse but the White fir is gray in color while that of the Red fir is more reddish. Final assurance requires your breaking a bit of the external bark scales off to reveal the subsurface colors. White fir bark, when broken will show creamy to orange, while that of Red fir will reveal an unmistakable oxblood-red.

A drive eastward toward the Old Donner Pass enables you to visualize the ancient extent of Lake Van Norden. Not much of a lake any more, it was once a reservoir for PG&E. They later dremoved the dam and the area has since filled in with sediments over time to become a boggy wetland. Prior to the PG&E reservoir, it was a shallow lake with broad meadow margins.

Today waterfowl and wildlife are attracted to these wetlands in spring and summer. In winter, cross-country skiers traverse its snowy expanse. You're approaching Donner Ski Ranch (left/north) and Sugar Bowl (right/south) resorts. This is the upper end of the broad trough that was carved by glaciers in both directions from the present summit (old Donner Pass – 7088 feet in elevation). Surrounding the bowl are the summits of Mt. Disney (7953'), Mt. Lincoln (8383'), Mt. Judah (8243') and Donner Peak (8019'). These peaks were sculpted and shaped by Ice Age glaciers that bulldozed eastward down to Donner Lake and westward through the valley from which you have just traveled.

If you wish to get a closer look at Western white pine and Red fir, take a detour over to Sugar Bowl's Main Lodge below Mt. Judah. Just past the first parking lot (Sugar Bowl gondola) take Sugar Bowl Road south. Very shortly, when you pass over the first track, look down into the narrow tunnel blasted into the rock for the passage of the early trains. At the end of this road, stop in the lower parking lot and step out for a look around. Western white pines have long, spindly branches and long, slender cones dangling from the branch ends. This subalpine cousin of the Sugar pine (also a white pine) has long branches from top to bottom.

Around the parking area are also Red firs which can be distinguished by scratching the outer bark and looking for the oxblood-red color. Scan the high slopes between Mt. Judah and Mt. Disney for another alpine species, the Mountain hemlock. Like the nodding-topped trees in books by Dr. Seuss, this hardy conifer climbs up the steep slopes where other trees fail. Their flexibility enables them to bend over and tolerate or shed the deep winter snows that fall upon them. This beautiful bowl, once the headwall of a large glacier, is now surrounded by granitic and volcanic rocks. Envision a massive glacier, thousands of feet thick, scouring this high-elevation Sierran region just 20,000 years ago.

This region has much recent historical significance as well. In 1925 Charlie Chaplin played his Little Tramp role in the silent film Gold Rush. Later, in the late 1930s, Walt Disney and others invested in developing this area and installed California's first ski lift.

Once back on Old Donner Pass Road continue to travel east to a major Sierran east-west watershed divide and the terminus of our I-80 tour. Donner Pass (7088 feet elevation) divides west-slope waters (here it’s the South Fork of the Yuba River) from the eastward flowing Donner Creek which runs into the Truckee River. Just before the pass you may see the signs for the Pacific Crest Trail, a 2600-mile trail that extends the entire span of our three western states, from the Canadian border to the California-Mexico line. A hike southward on the PCT will take you past Donner Peak and Mt. Judah (with a side trail up to Mt. Judah's top), then on your way to the top of Squaw Valley and further south. (See http://www.pcta.org)

The snowmelt that drains from Donner Pass forms a small creek and joins Donner Creek from Billy Mack Canyon on its way into Donner Lake. This beautiful glacially-carved lake at nearly 6000 feet elevation was also moraine-dammed. Below the lake Donner Creek flows eastward into the Truckee River (which flows from Lake Tahoe) and together, contributions from snow and rain travel through Reno to finally terminate at Pyramid Lake in the Great Basin.

Standing at the crest of two Sierran watersheds, the west-flowing waters of the Yuba watershed theoretically (unless they evaporate or are diverted by human activities) meet the Sacramento River and finally the Pacific Ocean. To the east, if a water molecule makes it past Reno in the Truckee River, there's a slight chance that it might make it to Pyramid Lake to nourish Cui-ui (an endemic fish in Pyramid) or even some Lahontan cutthroat trout along the way.

Don't miss the chance to admire the old Hwy 40 arched bridge (built in 1926 and restored in 1996) just a mile east down the road – there you can better enjoy the Donner Lake view. As you travel down to it you'll see rugged and twisted Sierra junipers wedged firmly into granitic cracks. A stop at the parking lot at the bridge will provide close inspection of the intriguing xenoliths (foreign rocks) welded into the granite. A short stroll upon the granite dome (south side of the bridge) will lead you to some picturesque and dwarfed Jeffrey pines. They form the krummholz shape (twisted wood) in response to harsh, high-speed winds, poor soils, and icy winter conditions. Look upwards on the steep southern slopes to spot more Mountain hemlock with their nodding tops.

Above these distant sub-alpine forests lies the alpine zone – the land beyond the trees. Hundreds of unique species of plants and animals have evolved myriad survival strategies that enable them to flourish in the land of long winters and short summers (another story for another time).

Stand and face eastward into America's Great Basin. Beyond the newly-fashionable village of Truckee, and Reno, the city that gambling made, lies an enormous geomorphic basin, mostly in Nevada and Utah (but also eastern Oregon, and California and parts of Idaho). With no connection to any ocean, the Great Basin's many rivers flow inward toward basin lakes where they eventually evaporate. Three major rivers that flow from the Sierra's eastern flanks are the Truckee, Carson, and Walker. Identified and captured early in human history for their agricultural value, these three Great Basin rivers once contributed greatly to highly specialized and flourishing semi-arid ecosystems.

Lahontan cutthroat trout (salmon-sized at 40 pounds and more) once flourished in large lakes like Pyramid and Walker. In only recent times, over-fishing, water diversions, and introduced fish species pushed this incredible trout to near-extinction.

The rise of the Sierra Nevada, beginning roughly three million years ago, raised a formidable curtain between moisture-laden Pacific air masses and the lands of the Great Basin. The Sierra Nevada range, joining with the Cascade volcanoes farther north, forged a rain-shadow wall. Collectively they created the various desert ecosystems of the present Great Basin. Behind you (west) are the lush mixed-conifer forests that Native Americans once called home. Tens of thousands of pioneers, miners, explorers, timber men, and railroad entrepreneurs followed and today, millions travel here annually for reasons from commerce to recreation.

If you continue from here, you'll drop downward and watch the vegetation change even more rapidly than while you ascended the pass. The subalpine forests of Mountain hemlocks and Western white pines will defer to Jeffrey pine and Sierra juniper. Farther down yet you'll find even drier slopes with Pinyon pine and Utah Juniper. Then, for hundreds of miles more, you'll drive through Great Basin sagebrush, saltbush, and Rabbit brush in the long and flat washes and playas. You will have entered the Basin and Range (graben and horst) Complex that will be your constant companion until Salt Lake City. I-80 will wind along side the Humboldt River and the historic California/Humboldt Trail as well as lead you through marvelous ranges like Nevada's Ruby Mountains.

The Sierra Nevada, John Muir's "Range of Light" exists today, bruised by centuries of rapacious Argonauts and lumberjacks, but illustrating remarkable resilience and responsiveness to change. Since the origins of Muir's Sierra Club (1892) hundreds organizations have been formed that wish to preserve, conserve, or at least judiciously manage the marvelous resources and opportunities that this mystical place has to offer. This short tour, a small slice across our 400-mile long range, hopefully whets your appetite for more – more exploration and more participation in its sustainable long-term future.

Sierra Nevada Conservation (a partial list)

Start at Envirolink (www.envirolink.org) to find a rich clearinghouse of environmental resources and organizations. (EnviroLink is a non-profit organization... a grassroots online community that unites hundreds of organizations and volunteers around the world with millions of people in more than 150 countries. EnviroLink is dedicated to providing comprehensive, up-to-date environmental information and news).

- Sierra Nevada Conservancy / www.sierranevada.ca.gov

Auburn Office / 11521 Blocker Drive, Ste. 205 / Auburn, CA 95603 / (530) 823-4670 The Sierra Nevada Conservancy initiates, encourages, and supports efforts that improve the environmental, economic and social well-being of the Sierra Nevada Region, its communities and the citizens of California. - Sierra Nevada Alliance / PO Box 7989 / 530.542.4546

South Lake Tahoe, CA 96158 / sna@sierranevadaalliance.org

- 80 member organizations (see list on website)

To protect and restore the natural resources of the Sierra Nevada for future generations while promoting sustainable community - Sierra Business Council / www.sbcouncil.org

PO Box 2428 / Truckee / 96160 / 530.582.4800

To secure the social, natural, and financial health of the Sierra Nevada for this and future generations. - Sierra Forest Legacy / www.sierraforestlegacy.org

915 20th Street / Sacramento / CA / 95811 / 916.442.3155 ext 207

- numerous member groups (see partners on website)

The mission of Sierra Forest Legacy is to engage citizens, communities, and coalition members in the healthy management of the Sierra Nevada forest ecosystem to protect and restore their unparalleled beauty and natural values. We apply the best practices of science, advocacy and grassroots organizing to safeguard forest lands throughout the Sierra Nevada. - Sierra Club, Mother Lode Chapter / http://motherlode.sierraclub.org/

801 K Street, Suite 2700 / Sacramento, CA 95814 / 916.577.1100

- numerous Groups represent Sierra Nevada areas and issues

- resources/links tab is an excellent resources for Sierra Nevada advocacy - Center for Sierra Nevada Conservation / www.sierraconservation.org

PO Box 603 / Georgetown, CA / 95634 / 530.333.1113 - Ebbetts Pass Forest Watch / www.ebpf.org

PO Box 2862 / Arnold, CA 95223

Ebbetts Pass Forest Watch was organized to oppose SPI's (Sierra Pacific Industry) plans for clearcutting. - Central Sierra Environmental Resource Center / www.cserc.org

PO Box 396 / Twain Harte / CA 95383 / 209.586.7440

CSERC has effectively served as the foremost defender of more than 2 million acres of forests, rivers, lakes, wetlands, roadless areas, old growth groves, scenic oak woodlands, and other precious areas within the Central Sierra - California Native Plant Society Redbud Chapter, CNPS / www.cnps.org / 2702 K Street, Suite 1 P.O. Box 818

Sacramento, CA 95816-5113 / Cedar Ridge, CA 95924-0818

(916) 447-2677 (Auburn, Rocklin, Grass Valley) 95816-5113 - Audubon Society Sierra Foothills Audubon Society / www.sierrafoothillsaudubon.com

PO Box 1937, Audubon-California Grass Valley, CA

765 University Ave Suite 200 95945-1937 Sacramento, CA 95825 (916) 649-7600 / - California Wilderness Coalition / www.calwild.org

1212 Broadway, Suite 1700 - Oakland, CA 94612 510-451-1450 - Clover Valley (Save Clover Valley) / www.saveclovervalley.org

- Dry Creek Conservancy / www.drycreekconservancy.org

(916) 773-6575 – Gregg Bates - dcc@surewest.net - Friends of the River / www.friendsoftheriver.org

915 20th Street - Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 442-3155 - The Nature Conservancy (TNC) / www.tnccalifornia.org

Sacramento Office / California Regional Headquarters 2015 J Street, Suite 103

201 Mission Street, 4th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814

San Francisco, CA 94105 415-777-0487 Phone 916-449-2850 - Nevada County Land Trust / www.nevadacountylandtrust.org

175 Joerschke Dr. Suite R / Grass Valley, CA 95945 / 530.272.5994 - Placer Land Trust / www.placerlandtrust.org

11521 Blocker Dr. Suite 100 - Auburn, CA 95603 (530) 887-9222 - Truckee Donner Land Trust / www.tdlandtrust.org

PO Box 8816 / Truckee, CA 96162 / 530.582.4711 - American River Conservancy / www.arconservancy.org

PO Box 562 - Coloma, CA 95613 530-621-1224 - Protect American River Canyons (PARC) / www.parc-auburn.org

PO Box 9312 - Auburn, CA 95604 - South Yuba River Citizens League (SYRCL) / www.syrcl.org

216 Main Street – Nevada City, CA 95959 (530) 265-5961 - Placer Legacy (County of Placer) www.placer.ca.gov/

Placer Legacy is a county-wide, science-based open space and habitat protection program (habitat, biodiversity, environmental quality, agriculture, open space, public safety).