California Quail

Ted Beedy and Ed Pandolfino

Authors, Birds of the Sierra Nevada: Their Natural History, Status, and Distribution

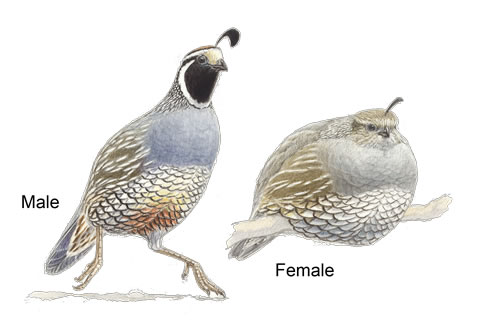

Callipepla californica – callipepla (beautifully dressed) from Greek kallos, and peplos (a robe).

This exquisitely plumaged quail is the “state bird” of California. California quail were a favorite game bird of native Sierra tribes, who snared them along their runways; head plumes and other feathers were used to adorn clothes and headdresses. Back-road travelers in the Sierra foothills sometimes startle large coveys of California quail, sending them running for cover or erupting into whirring flight in all directions. Rarely found above the foothills, they take shelter in chaparral, open oak stands, and streamside thickets but mostly feed in grassy openings. They do not migrate and may spend their entire lives in areas of only about two square miles. During the long, dry summers, they seldom venture far from streams, springs, or seeps that supply their daily water. At night, quail roost in heavily foliaged trees but will use dense shrubbery if necessary.

In fall and winter, California quail feed and roost in large coveys numbering from about 25 to 60 birds. They make a variety of clucks and calls for courtship, aggression, alarm, and maintaining contact. When separated visually, covey members utter a three-note assembly call, chi-ca-go, with the second note higher than the others. This call is given frequently in spring by pairs that are separated and by single birds seeking mates. Hollywood film-makers often use these sounds for background in almost any setting, including movies shot in Africa and Australia, hoping their viewers will not notice this gross biological error. Based on old episodes of Star Trek, they may be the most widespread birds in the galaxy!

Pairing Up

Males and females form monogamous pairs in late winter, gradually leaving the covey in late April or early May to find nesting sites—later than most resident birds. At this time, older unmated males establish small “crowing territories” to attract unpaired females. Their cow calls, similar to the last note of the assembly call are repeated several times per minute, usually for exposed perches in shrubs or trees. Each mated male defends his mate from other suitors but does not hold a nesting territory. Females construct nests by lining a small, well-hidden ground depression with plant stems and grasses. Young hatch in early June and stay with both parents through their first winter. In late summer, two or more of these family groups band together, along with nonbreeding individuals, to form a covey once again.

The staple foods of California quail are seeds and leaves of herbaceous plants, especially clover, lupines, tips of grasses, but acorns, fruits, wild berries, and large insects are also important. They usually forage on the ground, picking food from plants or scratching like chickens. Sometimes they move up into shrubs or even leap off the ground to snatch insects or seeds from plants.

Quail in the Sierra

California quail occur on both sides of the Sierra; while still more widespread on the West Side, they have become abundant in many East Side areas.

West Side. Common and widespread in the low foothills from annual grasslands and oak savannas to the Lower Conifer zone; primarily found in foothill chaparral, open oak woodlands and riparian woodlands near a source of water and grassy areas for foraging; avoids dense conifer stands and is rare or absent above about 3500 feet in the central Sierra; common in open Desert zone habitats, in the vicinity of oases, as in the South Fork Kern River Valley.

East Side. Uncommon to locally abundant throughout; recorded up to 8400 feet as Aspendell (Inyo County); their range has expanded from pre-settlement times likely due to a combination of habitat changes, artificial water sources and introductions; locally common near desert oases such a Butterbredt Spring.

Professional market hunters killed enormous numbers of California quail during the 19th century. Quail have very high reproductive rates, so while they are probably less numerous now than before that era, this decline is due mostly to habitat changes, fire suppression and land development. With enforced hunting limits, these gentle birds are once again common in suitable foothill habitats. Data from Sierra Christmas Bird Counts show a significant positive population trend in the past 30 years due largely to increases from nearly all the East Sierra count circles.

Taken with permission from:

- Birds of the Sierra Nevada: Their Natural History, Status, and Distribution

Edward C. Beedy and Edward R. Pandolfino. Illustrated by Keith Hansen.

UC Press. Berkeley and Los Angeles. 2013 - Quail illustrations by Keith Hansen

- Quail photo by Ted Beedy