California Grizzly

Jennie Skillen and Joe Medeiros

Sierra College

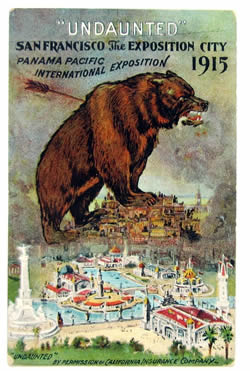

California—home to the Bear Flag, the Bear Flag Rebellion, baseball’s Fresno Grizzlies and UC Berkeley’s Golden Bears. But what bear do these names refer to? Today the only bear found in California is the American black bear (a bit of a misnomer, since its color can range from black to brown to cinnamon to almost golden). However, the black bear is not the bear the aforementioned names refer to. Instead, the bear found on California’s state flag and its state seal is the California Grizzly Bear. History has it that the last California Grizzly was shot and killed in 1922, giving the state the dubious distinction of being the only state to have an extinct animal designated as the official state mammal.

California’s apparent obsession with the bear and its name continue. In Gary Noy’s book (Gold Rush Stories) co-published by Sierra College Press and Heyday in 2017, he states:

The early Gold Rush grizzly omnipresence is reflected in profuse references to the bear in California place names. More than 500 locations are designated with “bear” as part of the name. There are seven Bear Rivers, twenty-five Bear Mountains, thirty Bear Canyons, and more than a hundred Bear Creeks. Additionally, there are waterways, meadows, and gulches identified as “Bearskin,” “Bearpaw,” and “Beartrap.” Two hundred or more spots are labeled “Grizzly,” including several Grizzly Peaks throughout the state and the old mining site named Grizzly Flats in El Dorado County. At least a dozen locations are identified with “Oso,” the Spanish word for bear. The grizzly adorns the California State Flag and the Great Seal of California. The mascots of several University of California campuses are bears.

The California Grizzly is Gone

The California grizzly is extinct today, but what kind of bear was it? To best explain California’s state mammalian symbol we’ll need to start with the brown bear. The brown bear, Ursus arctos, is found worldwide in the northern hemisphere, in North America, Europe and Asia, and once occurred in northern Africa as well. The species is divided into multiple subspecies, populations that differ from one another slightly in terms of size, coloration, or habitat.

The California grizzly was one such subspecies of the brown bear, and so its scientific name is Ursus arctos californicus. Other well-known subspecies of the brown bear include the Kodiak bear (Ursus arctos middendorffi), the grizzly of northern North America (Ursus arctos horribilis), and the Eurasian brown bear (Ursus arctos arctos). Common names are loosely applied, and collectively these bears are often termed “grizzlies” due to their pelage.

The Brown Bear

The brown bear is a relative to today’s Asian black bear, the American black bear and the polar bear, as well as to extinct species such as the cave bear featured in prehistoric cave paintings. Modern brown bears, including the recently extinct California grizzly, have existed for perhaps 1-2 million years, though periodic interbreeding with polar bears, Asian black bears, and American black bears has made it difficult to pin down the exact branching pattern of the bear family tree.

The California grizzly was an enormous bear, with a characteristic muscular hump over the shoulders that today’s more northern grizzlies also have. The hind foot of one adult male grizzly was measured at 12 inches long and 8 inches wide, and claws were often 2 to 3.5 inches long. Though they were mostly brown, there was variation in their color, with some hairs having pale tips which gave them a grizzled appearance. Some specimens were described as having a darker brown stripe along the spine and flanks. The long guard hairs often gave these bears a somewhat shaggy appearance, especially compared to the comparatively sleeker (and smaller) American black bear.

The Mexican Grizzly

The California grizzly was probably slightly larger than the Mexican (Sonoran) grizzly, another subspecies of brown bear that is also now extinct. Despite all the accounts, scientific and literary, of the California grizzly, Tracy Storer and Lloyd Tevis, in their 1955 book California Grizzly wrote “Seemingly, no one ever measured and recorded in print all the usual dimensions of a wild California grizzly.” However, these two scientists were able to combine information from a variety of reports to conclude that they were usually 6-10 feet long and 3-4 feet high at the shoulder.

The mass of the California grizzly is more difficult to determine, since few—if any—were ever weighed on accurate scales, and the size of grizzlies seen or killed may often have been exaggerated in reports. There are newspaper reports from the 1800s of bears weighing well over 1,000 pounds, and one captive bear was reported to be 1,100 pounds at his death. In comparison, the grizzlies of Alaska and Canada (Ursus arctos horribilis) are usually 6-9 feet long, 3-4 feet at the shoulder, and 200-850 pounds – males normally somewhat larger than the females.

A Southern California town, Valley Center, once called Bear Valley, claims to be the site of the largest grizzly bear ever taken (2200 lbs.) in 1866. This claim is contested but there is no doubt, the California grizzly was a very big bear!

10,000 to Zero

It’s hard to believe that there may have been as many as 10,000 California grizzlies roaming once about the state. Today there are none.

It’s hard to believe that there may have been as many as 10,000 California grizzlies roaming once about the state. Today there are none.

As early as 1896 C. Hart Merriam proclaimed that the California grizzly “unfortunately is rapidly approaching extinction.” The famous American mammologist studied the grizzly bear closely—so closely, in fact, that he once deduced that the bear (grizzly and brown bears) had as many as 86 variations, seven of which were in California alone. Modern genetic science has reduced this exaggerated number to only a few subspecies, the California grizzly is one of them, albeit now extinct.

In California, the grizzly was found everywhere excepting the desert. They enjoyed the plentiful resources of fish and flesh, nuts and berries and even fungi in California’s wild gardens. They were found commonly along the coast and its mountains, in the Delta, throughout the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys, in the Sierra Nevada to middle elevations and in throughout southern state, especially in the shrubby, chaparral-filled canyons of the Transverse and Peninsular Ranges.

John Muir's Observations

John Muir, California’s most famous early conservationist, almost playfully described the eating habits of what he called “the sequoia of the animals” in his book Our National Parks (1901).

To him almost every thing is food except granite. Every tree helps to feed him, every bush and herb, with fruits and flowers, leaves and bark: and all the animals he can catch, —badgers, gophers, ground squirrels, lizards, snakes, etc., and ants, bees, wasps, old and young, together with their eggs and larvae and nests. Crunched and hashed, down all go to his marvelous stomach, and vanish as if cast into a fire. What digestion! A sheep or a wounded deer or a pig he eats warm, about as quickly as a boy eats a buttered muffin; or should the meat be a month old, it still is welcomed with tremendous relish. After so gross a meal as this, perhaps the next will be strawberries and clover, or raspberries with mushrooms and nuts, or puckery acorns and chokecherries.

Unfortunately, it was this insatiable appetite, and the hoards of Euro-Americans that arrived during the Spanish-Mexican period and later the Gold Rush, that led to the rapid demise of the larger of our two California bruin species.

Grizzlies and Humans

Grizzlies reigned as the top of the food chain for thousands of years in California. Their first encounters with humans were with native Indians who both feared and worshipped them. Many stories were shared about encounters with California bears. Little fear was expressed for the smaller and more skittish bears (American black bear) but the brown bears were a different story.

Depending upon the tribal group, grizzlies were known to be incorporated into their culture—as spirits, demons, reincarnations, or even apparitions—but always with fear and respect. Before Euro Americans appeared on the scene with their firearms, Indians had no defense against a grizzly. Many unfortunates were undoubtedly killed in inadvertent encounters with the ursine kind and numerous observations were recorded of Indians being killed or maimed by grizzlies during the Spanish-Mexican or Vaquero period.

Depicting Grizzlies

The first known drawing of a grizzly came from Louis Choris, artist aboard the Rurik during the Kotzebue Expedition in 1816. But, the killing of bears began shortly after Spanish arrived in California to stay. In 1769, the first grizzly was killed by a member of the Gaspar de Portola expedition party—by a bullet from a blunderbuss near Los Osos, now near San Luis Obispo. They named the location Canada del Oso or the Canyon of the Bear.

It wasn’t long before grizzlies were being killed for their meat. In early 1772 Father Serra sent Commander Pedro Fages and some soldiers to kill bears for food for the missions. In this very same canyon the soldiers killed bears for 3 months. Approximately 9000 pounds of bear meat was sent to Missions San Gabriel and San Diego.

Thusly began California’s tragic decimation of the mammalian monarch that would later become the very symbol of the Golden State. By the early 1920s, all were gone.

Grizzly Exhibit

We now rue the loss of the California grizzly bear but nowhere other than Cal’s (UC Berkeley) famous Bancroft Library can one find a more fitting tribute to the mammal or a greater expose of human hubris and carelessness. Charles B. Faulhaber, the James D. Hart Director of UCB’s Bancroft Library said,

Through the lens of time, one can view the brutality, ignorance, romance, guilt, and 'redefinition' that characterize our treatment of this icon of California history.

An exhibit at The Bancroft in 2002 displayed hundreds of papers and artifacts that explored “… the physical extinction and the cultural resurrection of the California Grizzly Bear.”

While the exhibit has been taken down and its valuable treasures returned to safekeeping, the story lives on. There remains, however, a marvelous book by Heyday (Berkeley) edited by Bancroft librarian Susan Snyder called Bear in Mind (2003) and a wonderful website (http://vm136.lib.berkeley.edu/BANC/Exhibits/bearinmind/)

coordinated by Susan Snyder, Brooke Dykman and Erica Nordmeier, all staff at the Bancroft.

Between the book and the website, you can still dive deeply into California’s rich “grizzly” story.

Killing Grizzlies

Now, no one ever said it was easy to kill a grizzly bear. In 1910, James McCauley wrote,

He is very tenacious of life, and his coat of fur is so thick and his hide so tough, that it takes a good deal of killing to make him render up his life.

(from “How a Grizzly Stopped Berrying” in The Grizzly Bear – a magazine of the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West)

But nevertheless, in 150 years and ten thousand bears later, we were left without a single California grizzly.

In Westways, July 1934 (a Journal of the Auto Club of Southern California) Vance Hoyt wrote “The Passing of the King.”

With the invention of the repeating rifle, Old Ephraim's nobility, power and courage swiftly melted before the searing flame of gunpowder and lead. No being of flesh and blood could withstand the slaughter that followed. His kind fell by the thousands. Almost overnight the grizzly was forced to change his character and habits of living. The fearless ones suddenly became the great timid beast, who slept by day and stalked by night, and eluded conflict except when forced to fight for his very life. At long last the king had been subjugated by the butcher hand of civilization... The once ruler of the wild fastness of California became extinct because his only sins were greatness in size and fearlessness of mien (sic).

Grizzly as History Aid

A journey with Susan Snyder through her book or a visit to the Bancroft’s “Bear in Mind” website will carry the reader through the “modern history” of our relationship with the California grizzly. As Bancroft’s Charles Faulhaber says, the California grizzly “serves as a fitting microcosm for the study of California history from the 1700s to the present.”

In both resources one can read exhilarating stories of California’s wild and vibrant past. Hair-raising stories of grizzly encounters abound when bears were seen by the dozens each week.

You’ll read of bear hunts, bear traps, bear steaks, bear fat, and bull-and-bear fights. You’ll read about the famous Grizzly Adams and you’ll read of “Monarch” the last California grizzly in captivity—named so not for his status in the California ecology, but for The San Francisco Examiner, “the monarch” of the daily newspapers.

Monarch died in captivity in 1911 and the last California grizzly was shot in the southern Sierra in 1922. Numerous unverified sightings of live grizzlies trickled in for years after, but the fact remained—the California grizzly was gone, entirely and forever.

Should We Reintroduce the Grizzly in California?

In 2016, the Center for Biological Diversity, based in Arizona but with four offices in California initiated a campaign to enlist interest in reintroducing the grizzly in California. It was met with both applause as well as enthusiastic rejection. With California’s population hovering near 40 million (Montana has just over 1 million) fears of mortal encounters of the ursine kind dominated the news for weeks after the announcement.

Introduce them into the Sierran national parks? Wouldn’t this be guarantee human deaths? (In Yellowstone National Park, bears have killed eight people in 150 years—compare this with twelve deaths from falling trees and avalanches and five lightning strike deaths).

A recent book by a popular California author eloquently describes our past and current wildlife-people dilemma. Are we protecting the parks from the people, or the people from the parks? Jordan Fisher Smith’s Engineering Eden (Crown Publishing. NY. 2016) is detailed true story of people vs. grizzlies. Including various other significant issues that we invasive humans have forced upon nature, the book dissects our longstanding love affair with and simultaneous propensity to manipulate and regulate the natural world.

Grizzly in Art

So, the same state that put the grizzly on its flag is now resurrecting it to illustrate its defiance against the current White House and its interest in regulating California’s future. San Francisco’s 3 Fish Studios crafted a brave and bold California Grizzly (amidst poppies, of course) as well as other bear-ish Californiana to represent our independence. The studio’s generous philanthropic efforts range from supporting the arts in schools to the recent (2017) fire victims.

Without a single live grizzly in the state, California celebrates the powerful symbol in myriad ways—while the world-renowned bear flies daily on the state flag in tens of thousands of locations.

Sources and References

- Brewer, William H., 1966, Up and Down California in 1860-1864, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. (reprinted)

- Dillon, Richard, 1966, The Legend of Grizzly Adams: California's Greatest Mountain Man, University of Nevada Press, Reno, NV.

- Snyder, Susan. Bear in Mind: The California Grizzly. 2003. Heyday Books. Berkeley, CA.

- Bear in Mind online exhibit -- UC Berkeley - Bancroft Library http://vm136.lib.berkeley.edu/BANC/Exhibits/bearinmind/

- Storer, Tracy I. and Lloyd P. Tevis, Jr. (1955). 1996 Reissue. California Grizzly. University of California Press.

- Eric Rewitzer and Annie Galvin, 3fishstudios.com, California Rising Bear art

- Marone, Mark, photo of grizzly with fish