The Power of Trees

by Joe Medeiros

Sierra College, retired

Giant Sequoia

For more than thirty years I've transported busloads of students to giant sequoia groves in the Sierra. Each time I'd have them hold hands, extend their arms, and encircle a designated tree to see how many of us it would take to complete a chain around the massive plant. It would normally require more than 20 of us, young and old, to embrace the world's largest living things (and become official tree-huggers). I also took this opportunity to pick up a few of Wawona's freshly fallen cones, shake out a few seeds, and launch into a story about the wonders of trees, and plants, and anything else that could photosynthesize—manufacturing complex sugars from plain water and air. "It would take more than 200 of these tiny seeds to weigh a gram—the weight of a small paper clip,” I would enthusiastically announce. "And now look up! How did it get from here (the minuscule propagule perched upon my fingertip) to there (I'd point upwards toward the tree's crown)?"

I told this story, and many others like it, to my students, not simply for their knowledge, but for my benefit as well. I wanted to review for myself the marvelous processes that acted silently, and without apparent cost, within these and other forests of the world; processes that drew in thousands of gallons of water each day and transported them upwards hundreds of vertical feet; processes in the newest tender rootlets that exchanged hydrogen ions for precious atoms of magnesium, calcium, and other minerals; processes that took simple matter from air, soil, and water and deftly constructed goliath plants weighing a million pounds. And for what purpose? Each individual tree in the grove most likely acted for its own self-interests—to grow, produce needles, make sugars and starches for its metabolism and cellulose for wood—and to muscle its way upwards through nearby sugar pines and incense cedars with which it competed for precious light and other resources. Our chosen sequoia grew in order to produce seeds—to make more of its own kind—its only apparent (to us) mission. It was genetically programmed to do this each year, for thousands of years, to hedge its bets that its offspring would rise above the forest as well.

While these natural efforts seem selfish, our tree was also benefiting us—Lilliputian visitors to its personal montane haunt. It was providing us oxygen while also sequestering those trouble-making carbon dioxide molecules that escape and contribute to the warming our troposphere. Wawona was purifying the air and the water right where we stood. It was stabilizing the soils wherever its constantly growing root system could reach—keeping the nearby streams pure for fishes and the aquatic invertebrate life upon which they depended. It was providing us shade and immeasurable beauty. San Jose State University biologists Richard Hartesveldt, Tom Harvey, Howard Shelhammer, and Ron Stecker clearly had to be in love with this tree when they assembled the first definitive summaries of its natural history. These were grown-up men reveling in life and spending every available weekend and summer romping around like boys in one of the Sierra's grandest playgrounds—studying one of its most famous inhabitants.

"These giant sequoias are the biggest individual species in the world! More than 450 tons of biomass! Hell, if their boles were hollowed out, you could slide three blue whales into them—with room for a few orcas and whale sharks to spare! Seventy-five elephants could fit in there!" Somehow these examples never went over very well—but I kept using them for years. At the end of the day, after my sermons in the grove, we'd (calculatedly) end up at some even larger colossus for some quiet time. If we were in the South Grove of the Calaveras Big Trees, we'd lay on our backs at the base of the Louie Agassiz Tree to gaze upwards at this silent giant. High up in the canopy chickarees chattered with staccato shrill, scolding us for trespassing (without them, millions of sequoia seeds would remain within their cones. Preferring the meaty cone scales for nutrition, the voracious tree squirrels liberate the tiny seeds within). In the warming sun high above the forest floor, red-breasted nuthatches called like toy trumpets—hunting tasty invertebrate treats in the cracks and fissures of sequoia bark. Laying still, gazing upwards, most of us felt the power of the trees, trickling into our bodies, mingling like the smokes of two campfires, like spirits reunited after being separated for much too long. It was always hard to leave the grove.

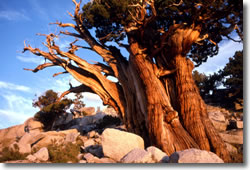

Sierra Juniper

Other trees of the Sierra have affected me like the giant sequoia. I could never simply walk by a Sierra juniper without stopping and taking a longer gaze. There's something about these handsome rock-dwelling relatives of cypress that give me pause at each and every encounter—I have never frowned at a juniper. Some of my favorite juniper groves are easily visited just a short stroll from the car at Carson and Sonora Passes. One can even follow a dirt track back to the Bennett Juniper, in the Stanislaus National Forest, purportedly the most massive of all Sierra junipers. A well-intentioned plaque placed at its base by the Clampers—the red-shirted, beer-guzzling, males-only Californian self-anointed historical society—tells (erroneously) of its extreme longevity. Countless specimens of majestic junipers exist throughout the Sierra. Numerous stately sentinels guard the western entrance to Evolution Valley along the John Muir Trail, where it follows the energetic South Fork of the San Joaquin River. They seem to enjoy positioning themselves in massive and fractured boulder fields, while still within view of roaring waterfalls and cascades like those plunging downward from Dusy Basin into the LeConte Canyon.

Other trees of the Sierra have affected me like the giant sequoia. I could never simply walk by a Sierra juniper without stopping and taking a longer gaze. There's something about these handsome rock-dwelling relatives of cypress that give me pause at each and every encounter—I have never frowned at a juniper. Some of my favorite juniper groves are easily visited just a short stroll from the car at Carson and Sonora Passes. One can even follow a dirt track back to the Bennett Juniper, in the Stanislaus National Forest, purportedly the most massive of all Sierra junipers. A well-intentioned plaque placed at its base by the Clampers—the red-shirted, beer-guzzling, males-only Californian self-anointed historical society—tells (erroneously) of its extreme longevity. Countless specimens of majestic junipers exist throughout the Sierra. Numerous stately sentinels guard the western entrance to Evolution Valley along the John Muir Trail, where it follows the energetic South Fork of the San Joaquin River. They seem to enjoy positioning themselves in massive and fractured boulder fields, while still within view of roaring waterfalls and cascades like those plunging downward from Dusy Basin into the LeConte Canyon.

One juniper grove stands out in my mind—without doubt my very favorite grove. It hovers in Yosemite, overlooking Washburn Lake and the Lyell Fork of the Merced River. On a lofty perch of massive intrusive rock, this collection of robust monarchs seems to radiate an energy that has beckoned us each time we've wandered into that little-visited corner of the Yosemite backcountry. In the warm summer afternoons this grove basks in the setting sun, unobstructed by other kindred mountain dwellers, where it begins to glow in the low-angle light—transforming from the crisp silhouettes of the morning cold into softer and inviting arboreal spirits—a fire that draws one to it, but lacking the pain of flame. Their shaggy brown overcoats change color, warming and illuminating, glowing an orangey-cinnamon that appears different than any other rival tree, even the sequoia. Their radiance calls us closer and invites us to lean against them to share the sundown. I've often wondered if this time of day is as spiritual and as pleasurable for them as it is for us. Do they find any comfort in the presence of Man? Nevertheless, we feel the grove's energy—unexplainable, but unmistakable. It feels different sitting there than when in camp. Something calls us to stay here longer—and saddens us when be bid farewell to the grove. It's more than simply a warming feeling; it's an almost indescribable sensation of strength, truth, acceptance, welcome, and understanding. It is the palpable presence of wildness that I think Thoreau was trying to explain. Memories of this grove are etched in our recollections, not only as three-dimensional "pictures,” but with an added dimension of deep sensation—gratitude for our acquaintance—enriched by the knowledge that these spirits were here long before us—and will be here still long after us.

Limber Pine

No one in their right mind would hike westward over Taboose Pass in a single day—not with a full backpack on. But some do. If they aren't consumed by the time they've climbed up 6000 feet in only eight miles from the dusty trailhead in the Big Pine volcanic field, they'll find themselves walking among one of the most spectacular forests of limber pine in the Sierra. Named for their flexible twigs that tolerate the heavy snow loads of the high country these pines were once well-known for being some serious old-timers. Edmond Schulman, who would go on to become one of the founding fathers of dendrochronology—tree dating—was studying limber pines out West when someone alerted him to the old bristlecones in California's White Mountains. Before long, the limber pines of the southern Sierra were forgotten in the frenzy to find the world's oldest living trees. Thousands of cores were bored into the ancient and contorted bodies of White Mountain bristlecones that lived across the Owens Valley—establishing that they were still alive more than 4000 years after they'd germinated from seed. Meanwhile the Sierran limber pines continued their quiet struggle to retain their hard-earned title as niche specialists of the arboreal kind in the upper treeline.

Found throughout the west, from the Canadian Rockies and throughout the mountains of the Great Basin, limber pine probably made it into the California by traveling through Basin and Range mountains, into the Inyos and Whites and westward to the highest regions of the Sierra and southern California mountains. Today they're found as far north as Yosemite—we've found them while scrambling down the volcanic rubble on the south face of Mammoth Mountain where they claim purchase among the stony flanks of the sleeping volcano. We've scrambled up steep granite slabs to find the limber pines in the Sawtooth Peak region of Mineral King – where they occupy lofty positions along high, sunny flanks of the Great Western Divide. Wherever they grow they reward us with impressive structure, artistic form, and the unspoken wisdom of thousand-year-old elders.

Convergent Evolution

The tell-tale wispy and upturned branches of Limber pines tell a story of convergent evolution—where two different species converge in form or function when subjected to similar influential forces. Like the whitebark pine found in similar subalpine conditions farther north, the long and spindly upper branches of foxtail pine seem to reach eagerly towards the sky. The purpose of this seems simple: to offer large, stony, and wingless seeds to passing birds—in hopes to have them dispatched to nearby uncolonized ground, thereby expanding the territory of the species. Ron Lanner, dean of the worldwide association story of pines and jays, eloquently describes this mutualistic symbiosis in his book Made for Each Other. In Conifers of California he proffers an explanation of why whitebark and limber pines, while distantly related (genetically) both exhibit open, wispy branching at their tops. Research shows that ancient ancestors of whitebarks entered the western cordillera from Asia via the Arctic land bridge while foxtail relatives forged their slow path northward from the mountains of Mexico. Whitebark pine brought its "Johnny Appleseed" counterpart, an Asian nutcracker, along with it, while ancestral foxtails cooperated with southern jays in the Sierra Madre. Once the foxtails arrived in the southern Sierra, the nutcrackers (by now a new species) applied their avian handiwork to the morphology of both whitebark and foxtail pines. Choosing to excavate wingless seeds from the most highly advertised cones (attached to the tallest and most upswept branches), the Clark's nutcracker selected for the form that is represented now by both pine species. Who won this struggle for survival? They all did! While limber pine stakes out a few sites where it can dominate the forest niche, it commonly gives way to the foxtail pine.

Foxtail Pine

I first became acquainted with foxtail pine on Alta Peak in Sequoia National Park. High above me on this Kaweah watershed spire, a small forest of hardy trees seemed to crawl up the slope towards the 11,000-foot summit. After a long walk up to take a closer look, I became a true admirer and lifelong student of this wonderful species. Years later, after an arduous introduction to Kearsarge Pass from Onion Valley on the Sierra's eastern flank, I was reintroduced to this close relative of bristlecone pine. While whitebark pines and mountain hemlocks dominate the lofty tree-niches of the northern and central Sierra, the foxtail and limber pines occupy comparable treeline haunts in the south. The bottlebrush form of the foxtail's twigs made me think immediately of the bristlecone pines that I had admired in the neighboring White and Inyo Mountains to the east. Closer inspection of the foxtail's needles and cones left no doubt among professional botanists that this tree belonged in the pine subfamily Balfourianae, that of the oldest of the world's trees. Unlike the bristlecones of the White Mountains and the Great Basin, whose forms were mostly twisted, or krummholz, in response to high-speed winds and long, harsh winters, the foxtails of the Sierra form robust forests of stout-trunked individual trees. Widely separated but with massive bases, their leading tops are often dead and the trees taper up quickly to barren armatures of barkless branches—exposed wood lacking its protective cover.

All variety of forms exist and no two are alike—from the stout and tall to the leaning and the asymmetrical (like flags indicating telltale winds). The needles of these California endemic pines are fascicled in bunches of five and their cones are slightly elongated, deep purple in color, with tiny prickles punctuating each imbricate cone-scale—relating them to the famous bristlecones. Their characteristically checkered bark is immediately recognizable once one has become acquainted with these old ones. Unique to California, the foxtail's geographic distribution is puzzling, separated by a gap of 300 miles; two populations exist in the state. One disjunct population flourishes in the Klamath Ranges in the northwestern region of the state. The other, larger population flourishes in the southern Sierra high country. It was here where our fondness for foxtails flourished.

High-Elevation Forest Zones on the John Muir Trail

Our treks along the John Muir Trail are subdivided (in our minds) in many ways – “sections between resupplys,” “watersheds of Sierran rivers,” “high country and low valleys,” “before crossing-over and after” (another story yet to be told). But the compositions of upper elevation forests also exist as categorical benchmarks in our minds—the northern whitebark-hemlock forests, the central limber pine forests, and the southern foxtail forests. While we certainly have walked right past the northernmost foxtail of the Sierra, we first recall seeing them on the trail, when traveling southward, after climbing over Pinchot Pass. On the south side of the divide, in the looming shadows west of Mt. Cedric Wright our first foxtails appear—first as solitary individuals for miles along the trail until we find the first stands basking in the warm metamorphic soils east of the Baxter Creek junction. Tall but tortured individuals in the upper canyon give way to denser but open forests of foxtail families as we walk downriver. Their foothold increases below the Castle Domes where they line both glacially-scoured walls of the Baxter Creek canyon. For the Muir Trail hiker the land of foxtails begins here. Their forests grace the high country of Kings Canyon and Sequoia National Parks and even farther south into the upper reaches of the Inyo and Sequoia National Forests. On the way southward the mountain traveler is treated to luxuriant foxtail forests through the famous Rae Lakes and Sixty Lakes Basins, surrounding Kearsarge Pass, and all along Bubbs Creek from Vidette Meadow to every nearby treeline.

Even though the southern Sierra is replete with foxtail pines, we've never gotten enough of these luxuriant conifers. They provided our Sierra saunters with open but verdant treescapes—especially from the upper Kern River drainages below Mt. Tyndall to the Whitney massif, part of a bold collection of 14,000-foot peaks. We walked, literally energized by their presence, through foxtail forests, one after another, around Tawny Point, the Bighorn Plateau and all the way up from Crabtree Meadow to Timberline Lake—a common basecamp for a Mt. Whitney ascent. Thousands of thousand-year-old trees embraced us all along our pathway. From lofty haunts, even older trees (some maybe even two or three thousand years old) must have observed us along our odyssey at the upper edges of the Sierra's treeline. Our already protracted pace was slowed even more by the desire to closely inspect one magnificent individual after another. We have truly connected with these ancient spirits and they have given us much.

The Power of Spirits Reuniting

When spirits reunite, there are powerful forces that converge. The past and even the future are re-presented at the same moment. While the history of each species lies, like a frozen record, in the tightly coiled archives of the nucleus, the ability to adapt to the future lies at the very same locus, quietly awaiting the stimulus that will awaken its purpose and potential for change. The power of trees beckons spirits upon which its life is dependent, as well as those for whom its own body will provide nourishment—roots and fungi, trunks and beetles, twigs and caterpillars, needles and grouse. Ten thousand years of our star's powerful rays lie quiescent, fixed in the rigid strands of wood and flexible fibers of leaves—in the ever-so-slow dance of transformation—from burning light to sweet sugars—from sugars to fibers of cellulose—from fibers to the bodies of creatures—from bodies to motion—and from motion to the long infrared rays that will wander without direction or apparent purpose into chaos, to which all life is inevitably destined.

If one is willing—and receptive—locating forces such as these require only a walk in the woods or a stroll along the beach. With or without vision, eyes open or closed, such forces draw us to them like iron filings to a magnetic field. For some the calling comes from crashing waves on the coast. For others, it's the celebratory calls of sandhill cranes flying three miles above as they pass overhead to their wintering grounds. For me it’s the aura of wisdom—and time—and tolerance—and patience I find in old trees. It's the power of these trees that anchors me firmly to my one and only worldly home—and my special place, the Sierra.

Can These Ancient Trees Survive “Lord Man?”

What lies in store for all of Earth's ancient tree-people? Will they survive another millennium? Are the changes that we, as a new species in their neighborhood, have wrought prove too much for their seemingly invulnerable longevity? Do they watch, or listen, as we annihilate their kin in "managed" forests, malls, and residential housing tracts? They have survived flood and drought. They have awaited the end of century-long dry spells, record snowfall winters, monsoonal episodes, beetle infestations, and even axes and chainsaws. But will they survive the exponential onslaught of human overpopulation? Overexploitation? Avarice? Will Lord Man, as Muir so aptly described us, overwhelm billions of years of nature's tinkering and fine-tuning? Will we ever be able to measure the value of trees and forests without thinking in board feet? Cancer-curing drugs? Watersheds? Campgrounds? Hunting areas? Dollars? Will we ever be able to conceive of the value of trees from any other perspective than that of our own utility?

We have never been so numerous before. We have never lived at such exorbitant levels of affluence. We have never wanted so much more than we need. We have never converted so much of Earth's life-giving habitat for our explicit use. We have, quite frankly, never played such a dangerous, dangerous game.

Will our grandchildren be able to hike along a high ridge in the Sierra and lean against an old juniper? Feel its energy? Mingle with its spirits? Will they be able to scramble up a sparkling granite slab to touch a limber pine? A foxtail? If not, then, what will they have? What will they have to connect themselves? To reconnect themselves? From where will their power come?