The Sierra College Natural History Museum: A History

By Keely Carroll

Professor of Biological Sciences, Sierra College

Born in a Garage

What today is known as the Sierra College Natural History Museum was born in the garage of Sierra College zoology professor Ray Underhill in the early 1960s. Dr. Underhill taught at Placer College (the original name of today’s Sierra College) and Sierra College for more than twenty years and was Chair of the Natural Sciences Department for most of that time.

Like many biology departments of the period, Sierra College had a small teaching collection that contained preserved specimens and study skins of many animal species. Those teaching collections were typically used to show college students representative organisms that were discussed in their classes, but Dr. Underhill felt that others could benefit from them as well. He started borrowing specimens from the teaching collection to take home to share with children from his neighborhood and developed a makeshift classroom in his garage. So began what would later be dedicated as the Ray Underhill Life Science Museum, sometimes referred to as the Sierra College Science Center or the Science Center and Natural History Museum, has since 1997 been officially named the Sierra College Natural History Museum.

Construction of Sewell Hall

At the same time that Dr. Underhill was unknowingly planting the early seeds of the Natural History Museum, Sierra College was beginning construction of the new Rocklin campus. This new facility would include the construction of a Science building that would be designated Sewell Hall. The building was named in honor of J. Gordon Sewell, a chemistry instructor at Placer College from 1939 to 1955. The new building was to be built on a 43-acre site that included part of Secret Ravine and its surrounding riparian corridor. It also included historical Native American acorn grinding rocks. Sewell Hall was to be built in two phases, with the first phase completed around 1960. In 1964, the college received the first major donation to its fledgling science museum.

First Major Donation

In 1964, Dr. Nathan Dubin, an African big game hunter, approached the college about donating his collection of specimens to the college. With the approval of then Sierra College President Harold Weaver, the maintenance staff mounted the specimens in February 1964. The collection, which included head mounts of animals such as a Kudo, a Gensbok, a Springbok, a Cape Buffalo, and a Zebra skin were displayed in a manner that allowed the specimens to be seen from Rocklin Road.

A Special Designation

In 1965, when the second phase of Sewell Hall was in the planning stage, Dr. Underhill saw the opportunity to create an actual museum space within the building that could extend the public outreach of the campus. Astronomy professor Bob Duke wanted to include a Planetarium in the museum design. President Weaver approved the proposed design. Weaver realized that the desire for such as facility already existed in the community as Dr. Underhill had elementary school classes regularly touring the zoology lab. President Weaver went one step further and approached the Sierra College Board of Trustees for additional funds to encircle the room with large, enclosed glass display cases that could be used to house dioramas and other exhibits. The result was a centrally located museum room called Sewell Hall 110.

The special designation of Sewell Hall 110 as exhibit space was a major accomplishment in the development of a California community college. Typically, when new rooms are built on a college campus, they are labeled as instructional space, which means that the campus must fill them with students before they can request new buildings from the state. With the exhibit space designation, the campus would not be required to fill the room with students and the space could be reserved for the museum. This is a rare designation, and Sierra College is one of only a few community colleges with such a room. Today, in recognition of Ray Underhill’s efforts, Sewell Hall 110 is designated as the Dr. Raymond Underhill Natural History Museum.

Growth of the Natural History Museum’s Collections

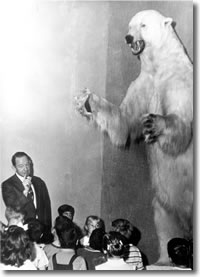

Once the Sierra College Natural History Museum had a home, it was destined to grow with the addition of new specimens and a supply of much needed funds. Following Dr. Dubin’s donation, more contributions followed. Most notable among these was a Polar Bear Mount from the Koshel Family. This impressive specimen of a standing polar bear greets visitors as they enter Sewell Hall. The Koshels also proved a mounted Walrus head.

Once the Sierra College Natural History Museum had a home, it was destined to grow with the addition of new specimens and a supply of much needed funds. Following Dr. Dubin’s donation, more contributions followed. Most notable among these was a Polar Bear Mount from the Koshel Family. This impressive specimen of a standing polar bear greets visitors as they enter Sewell Hall. The Koshels also proved a mounted Walrus head.

Not long afterward, Dr. Don Hemphill of Pacific Union College sold his collection of bird and mammal study skins to the museum. More donations followed and soon storage became an issue. Dr. Underhill anticipated the need for additional storage within the new museum. He asked the Sierra College Board for more funds to purchase even more cabinets for the new space. The Board very creatively decided that the new cabinets should match the rest of the building and absorbed the cost in the budget of Sewell Hall construction.

National Science Foundation Grants

In 1965 the National Science Foundation awarded Sierra College a portion of a $250,000 grant from the National Defense Education Grant program, which was designed to increase the level of science education in the United States. In 1967, the College received an additional grant from the National Science Foundation in the amount of $50,000. Those two grants made it possible for Dr. Underhill to work part-time in the museum as its curator and part-time as the zoology instructor. That grant also paid for the addition of student help to the museum staff.

In approximately 1967, some of the first people to be hired as museum student help under that grant were Jim Wilson, Harriet Sindel (now known as Harriet Wilson, Microbiology professor), Sam Gittings, and Lewis Jones. They, along with other student help, were charged with the development of live animal and museum displays and artwork. Ever the educator, Dr. Underhill was adamant that those funds would be used to hire Sierra College students to work in the museum. Thanks to the grant, Dr. Underhill was able to pay the students for their work and the students gained valuable experience that they could used to enhance their resumes.

In approximately 1967, some of the first people to be hired as museum student help under that grant were Jim Wilson, Harriet Sindel (now known as Harriet Wilson, Microbiology professor), Sam Gittings, and Lewis Jones. They, along with other student help, were charged with the development of live animal and museum displays and artwork. Ever the educator, Dr. Underhill was adamant that those funds would be used to hire Sierra College students to work in the museum. Thanks to the grant, Dr. Underhill was able to pay the students for their work and the students gained valuable experience that they could used to enhance their resumes.

In 1968, the Sierra College Science Club, under the direction of Botany professor Roland Bergthold, designed and constructed a nature trail that traversed the Secret Ravine riparian corridor that was part of the campus.

Community Outreach

In the 1960s, the Community Services Program was started at Sierra College. Funded by a ½ percent tax per every $100,000 assessed property value in Placer County, the program was designed to provide community outreach and to offer services that would best be supplied by the college.

Jim Wilson, who had left the museum program to complete his degree at CSU Chico, returned in 1971 as a Community Services Multimedia Specialist/ Liaison for the Biology department. Edna DeVore was also hired as the Liaison for the Astronomy program. Since both were hired to do Community Outreach, they designed educational programs for the Life Science Museum and Planetarium. The two would travel to the elementary schools of the area and present slide shows to teachers of fourth through sixth grades. These shows demonstrated what the museum program could do for their students. Teachers who were interested in participating in the museum programs would then sign up to take classes on the academic areas associated with the programs offered by the museum, such as ornithology, mammalogy, ecology, marine biology and astronomy. This would help the teachers better educate their students. As an extra benefit, since they were able to sign up for the teacher educational programs through UC Davis Extension, the teachers would also receive credit that could be used to receive increased pay.

As part of this outreach program, the teachers would be given a museum kit. The kits contained a student manual for each student; a teacher’s manual; slide sets to accompany the materials in the manual, and study skins for the students to examine. These materials were entirely designed and maintained by the museum staff. The kits were lent to the teachers for two to three months. Once the students had learned about the subjects from the provided materials, they would receive a guided tour of the museum and engaged in hands-on activities that focused on what they had learned in class. For those teachers who wanted more for their students, field trips were offered to either the Pacific Coast or the Sierra Nevada, typically guided by Jim Wilson, Harriet Wilson and museum student help. Usually two classes of elementary or secondary school children were bussed to Mendocino/Fort Bragg area for three days to study ecology and marine biology, which included guided activities in the tidepools, beaches, and redwood forests. Similar trips were scheduled to the Sierra Nevada to study the mountain environments.

Over time the Community Services Program extended beyond the fourth through sixth grades. Kits and programs were developed for kindergarten through 12th grade, with special units for each grade that reflected current developments in science. Seventh and eighth graders were provided with a “Mountain Environments” program that included the developing field of ecology combined with other related fields, which made use of the materials in the museum and the nature trail. The museum programs were never stagnant, as they were constantly revised and updated during the life of the Community Services Program.

Family Day and Other Programs

In the 1970s, the museum extended its outreach beyond the classroom and into the homes of the local communities, especially those in Placer and Nevada Counties. Family Day was established as a program that could appeal to all members of the community. Held on Saturdays, the program included lectures by faculty and special guests, nature area tours, science film screenings, interactive laboratory demonstrations and activities for each discipline, and local artists sketched drawings for visitors on demand. Each family day program was centered on a particular theme and was totally free to the public—often as many as 3000 visitors would be in attendance.

During this period of time, Community Services and the museum offerings expanded into presenting a variety of evening multi-media and planetarium programs for the public on a variety of astronomy and biology/ecology topics. These were locally written and produced using a combination of five screens for slides and movies and the planetarium star projector. Each presentation was scheduled monthly, showing every Wednesday and Friday evenings throughout most of the year. The "Christmas Star" (Astronomy) and "Wild Travelers" (Life Science) were among the first shows to be given. These programs included slides, video (movies), narration recorded with music backgrounds and special sound and other visual effects that was projected onto five screens that would blend and fade into one another, timed to the script. The programs were wildly successful and additional programs were continually being produced by the museum.

The Impact of Proposition 13

Annually, thousands of elementary students visited the museum and marveled at what they saw, benefiting from what they experienced. Teachers improved their instructional skills. The public learned about the environment. Community outreach programs helped to inform the public of the programs offered by the college and Community Services and helped increase campus enrollment. But it was not meant to last.

Annually, thousands of elementary students visited the museum and marveled at what they saw, benefiting from what they experienced. Teachers improved their instructional skills. The public learned about the environment. Community outreach programs helped to inform the public of the programs offered by the college and Community Services and helped increase campus enrollment. But it was not meant to last.

In 1978, California’s voters passed Proposition 13, which eliminated the Community Services Tax and dried up funding for the museum. In the final year before the passage of Proposition 13, approximately 27,000 students and local residents, some from as far away as the San Francisco Bay Area, visited the museum. After serving more than 150,000 members of the public over the years, the program was summarily shut down.

The impact of Proposition 13 on the museum was severe and immediate. Years passed without anyone to look after the museum’s materials. Professors wanted to continue some of the museum’s programs but could not find the time or the funds. Jim Wilson, who was laid off when Proposition 13 was passed, was later hired as a lab technician for the biology department. He wanted very badly to restart some of the programs that had previously functioned through the Community Services Program, but was told that he could not. Over the years, museum specimens would succumb to insect infestation and neglect. Sadly, hundreds of specimens were lost.

Sierra College Foundation Natural History Museum Committee

Then, in the early 1980s, a handful of faculty and staff including, current chair Richard Hilton and vice chair Shawna Martinez, zoologist Charles Dailey, former Community Services Liaison Jim Wilson and former museum display artist Harriet Wilson, came together to form The Sierra College Foundation Natural History Museum Committee.

The committee hoped to reinvigorate the public educational programs that the museum had provided in the past, and to save the remaining specimens in the collection. Attempts were made to obtain funding for the museum projects—via two bond measures, requests to the college for permanent funding and from grants—but none were successful. Without a steady, permanent flow of money to sustain programs, the museum committee could not hire the requisite personnel to keep the programs going. That did not mean, however, that there was nothing that the committee could do.

New Exhibits, New Specimens and the Natural History Museum Lecture Series

Over the years the museum committee has acquired dozens of new specimens, including many fossils found by its members. These include a Gomphothere and an Irish Elk. It has also attained displays of many mammal species, including an elephant, two rhinos, a Grey Whale (see the article on “Art the Whale” in this issue to discover the lengths some members will pursue to add to the museum collection), and hundreds of mineral and plant specimens. The Arboretum that was started by Roland Bergthold, was expanded with new plantings through the efforts of Shawna Martinez and Jim Wilson as well as others. Another arboretum has been planted on the other side of campus. A cactus/desert rock garden is located outside the west entrance to the museum in Sewell Hall, largely due the advocacy and work of Dick Hilton. It is representative of the three desert ecosystems in the west.

Over the years the museum committee has acquired dozens of new specimens, including many fossils found by its members. These include a Gomphothere and an Irish Elk. It has also attained displays of many mammal species, including an elephant, two rhinos, a Grey Whale (see the article on “Art the Whale” in this issue to discover the lengths some members will pursue to add to the museum collection), and hundreds of mineral and plant specimens. The Arboretum that was started by Roland Bergthold, was expanded with new plantings through the efforts of Shawna Martinez and Jim Wilson as well as others. Another arboretum has been planted on the other side of campus. A cactus/desert rock garden is located outside the west entrance to the museum in Sewell Hall, largely due the advocacy and work of Dick Hilton. It is representative of the three desert ecosystems in the west.

The Natural History Museum Lecture Series, offered monthly, continues at the museum. This long-standing museum fixture features recognized experts from many diverse fields lecturing on a wide variety of topics, such as predaceous plants, conservation, geology, and ecosystem ecology.

The Museum offers tours of the facility led by student docents. These tours can be scheduled through the Museum website at http://www.sierracollege.edu/museum/ . These fascinating explorations are suitable for both young and old.

The Natural History Museum’s Role at Sierra College

The Museum is an integral component in the education of Sierra College students—through the use of specimens in lectures, museum tours, educational displays, numerous field trips to collect more materials for the museum, and through the community lecture series. It provides current college students with an experience unlike any found at other Community Colleges in California. Future students, college employees, and the public are also drawn to the Museum’s displays and programs.

Prospects for the Future

The Sierra College Natural History Museum Committee, which is composed of an all-volunteer membership, still strives to revive many past programs and expand its current offerings. The Museum is constantly searching for revenue sources, with an active membership program (also available through the website listed above) and plans for a major fundraising event in September 2009. They continue to maintain the collection, add displays to the Museum and to present a small-scale educational outreach program.

As years pass, it becomes more difficult to remember the programs that the museum once provided. Many of the children that were served by past museum programs have grown and many of their teachers may have moved into retirement; but memories remain. What a wonder it must have been, as thousands of children and adults toured the museum facility—being educated by generations of teachers, and perhaps experiencing that extraordinary moment when they first realized their connection to the earth. We would be hard pressed to think of a single program like that existing today— that is a sad thought.

In the growing neighborhoods of nearby Rocklin, other communities in Placer and Nevada Counties, and the greater Sacramento Valley, how many children might benefit from an active museum educational program like that of the past?