Alonzo Delano: Nomad Denizen of the World

by Gary Noy

Center for Sierra Nevada Studies

… Part 2, continued

Into the Mountains

As the wagon company continued toward Fort Hall, in today’s Idaho, the trail had become more and more difficult to bear. The intrepid sojourners had been gone a long time, nearly four months, and seemed no nearer their goal. At times, Delano noted, the trail became eerily quiet.

As the wagon company continued toward Fort Hall, in today’s Idaho, the trail had become more and more difficult to bear. The intrepid sojourners had been gone a long time, nearly four months, and seemed no nearer their goal. At times, Delano noted, the trail became eerily quiet.

I had walked six miles during the day, and now I was to try my bottom on one of the most severe attempts I had ever made. Slow, but steadily, we walked on. The night closed in upon hundreds of wagons, and the road was lined by horsemen and pedestrians, and lucky was he who had the good fortune to have the shadow of a mule to ride. All walked who could, in order to make their loads as light as possible, to save their cattle; and as the night wore heavily on, all sounds of mirth or of loud profanity ceased, and the creaking of wheels and the howling of wolves alone were heard. (11)

As the Fourth of July 1849 dawned, Alonzo Delano had discovered some friends travelling in a separate company. It lightened his mood, which was sorely needed as Delano also suffered a most unexpected flare-up of his ailment.

… as the sun arose over the eastern mountains this morning, certain unmistakable signs warned me that “the end had not yet come.” The cold chills which were dancing along my back, gave me an inkling how my fourth of July was to be spent. Dear reader, may you be spared such a celebration of our glorious anniversary as I was doomed to endure. My old enemy nailed me to my bed, and kept me there, rioting in fever and chill, till after high noon. It was four o'clock in the afternoon before I was well enough to crawl out, and gather the news of the camp. (12)

Turning south from Fort Hall along the California Trail, Delano passed by a remarkable landscape — the City of Rocks, also in present-day Idaho:

Turning south from Fort Hall along the California Trail, Delano passed by a remarkable landscape — the City of Rocks, also in present-day Idaho:

From the summit of the hill, a fine and peculiarly interesting view was afforded. It had evidently been the scene of some violent commotion, appearing as if there had been a breaking up of the world. Far as the eye could reach, cones, tables, and nebulae, peculiar to the country, extended in a confused mass, with many hills apparently white with lime and melted quartz — some of them of a combination of lime and sandstone — perhaps it might be called volcanic grit; while others exhibited, in great regularity, the varied colors of the rainbow I have seen the broken hills exhibit, in parallel lines, white, red, brown, pink, green and yellow, and sometimes a blending of various colors. (13)

Soon the company passed by the American Falls of the Snake River in Idaho, a scene sketched years earlier by Charles Preuss of the Fremont Expedition, and the trail became more harsh, drier, and dustier as they approached the desert. The dust particularly bothered Delano. That irritation and the lingering effects of his illness lead Alonzo Delano to adopt an interesting sleeping strategy.

One of the most disagreeable things in traveling through this country is the smothering clouds of dust. The soil is parched by the sun, and the earth is reduced to an impalpable powder by the long trains of wagons, while the sage bushes prevent the making of new tracks. Generally we had a strong wind blowing from the west, and there was no getting rid of the dust. We literally had to eat, drink, and breathe it. Two miles below our encampment the mountains again reduced the valley to a cañon, which was impassable for wagons, and we were obliged to cross a spur, eighteen miles in extent, before we reached the river again.

I was taken with dysentery during the night, and being too weak to walk, I had to take up uncomfortable quarters in my “moving lodge.” On arriving at the river, after passing the rough mountain, I felt much better, and spreading my buffalo skin in the open air, slept well. From this time till we reached the valley of the Sacramento, I discarded the tent altogether, and from choice slept in the open air without inconvenience, and indeed long after I reached California. (14)

The Black Rock Desert

Now, the brutal Black Rock Desert of Nevada lay before Delano — a hardship of physical and psychological enormity. There was no water, just mile after mile of searing desert.

Now, the brutal Black Rock Desert of Nevada lay before Delano — a hardship of physical and psychological enormity. There was no water, just mile after mile of searing desert.

Daylight showed us nothing but rugged, barren mountains, and instead of the grass we had been assured of, there was not a blade to be seen. All that there had been grew on a little moist place, irrigated by three small springs, and this trifle had all been consumed by advance trains. The water from the springs sank into the ground within five rods of their source, and entirely disappeared. It was now twenty miles or more to Rabbit Springs, the next water. Our wagons had passed during the night, and were far in advance, so that we had the prospect of a late breakfast before us. Taking a parting drink from the pure fountain, we pursued our way in a north-west direction up the gorge to the ridge, and then following down another ravine. At the distance of five miles from the spring we were upon the north-eastern rim of another barren sand-basin, in view of a broken country far beyond. About the centre of this basin, we overtook a wagon, standing by the road-side, when we begged for a drop of water; but, alas! they had none for themselves, and we were obliged to go on without.

Crossing the basin and ascending a high hill, we overtook our train, just entering another defile on the north-west, when we refreshed ourselves with a cup of tea, made from the acid water of our vinegar keg. It revived us, and we pushed forward, anxious to reach the promised spring, for our cattle as well as ourselves stood greatly in need of water. The day was excessively warm, yet we hurried on, and descending a couple of miles through a defile, we passed the most beautiful hills of colored earth I ever saw, with the shades of pink, white, yellow and green brightly blended. Volcanic mountains were around us, and under ordinary circumstances we could have enjoyed the strange and peculiar scenery. (15)

In the Black Rock, Delano met a young mother and child, waiting for relief, hoping against hope, and the searing moment nearly broke his heart.

High above the plain, in the direction of our road, a black, bare mountain reared its head, at the distance of fifteen miles; and ten miles this side the plains was flat, composed of baked earth, without a sign of vegetation, and in many places covered with incrustations of salt. Pits had been sunk in moist places, but the water was salt as brine, and utterly useless. Before leaving Rabbit Spring I had secured about a quart of water, in an india-rubber flask, which I had husbanded with great care. When a few miles from Black Rock Spring, I came to a wagon, standing in the road, in which was seated a young man, with a child. The little boy was crying for water, and the poor mother, with the tears running down her cheeks, was trying to pacify the little sufferer.

“Where is your husband?” I inquired, on going up.

“He has gone on with the cattle,” she replied, “and to try to get us some water, but I think we shall die before he comes back. It seems as if I could not endure it much longer.”

“Keep up a stout heart,” I returned, “a few more miles will bring us in, and we shall be safe. I have a little water left: I am strong and can walk in — you are welcome to it.”

“God bless you — God bless you,” said she, grasping the flask eagerly, “Here, my child — here is water!” and before she had tasted a drop herself, she gave her child nearly all, which was but little more than a teacupfull. Even in distress and misery, a mother's love is for her children, rather than for herself. (16)

From the Black Rock desert, Delano took the Lassen Trail (or Applegate’s Cutoff, depending upon what source you believe) toward California. Delano would later recall this as “the second great mistake on the journey,” as they lost time and nearly ran out of provisions.

The Promised Land - California

But, suddenly, Delano spied the promised land — California — with his first glance of the magnificent Sierra Nevada. But jubilation was mixed with trepidation as Delano feared that one last calamity would befall the wagon company and dash their dreams:

… we became aware that we should soon be in the California mountains, and on the last end of our tedious journey. …

The Siérra Neváda — the snowy mountain so long wished for, and yet so long dreaded! We were at its base, soon to commence its ascent. In a day or two we were to leave the barren sands of the desert for a region of mountains and hills, where perhaps the means of sustaining life might not be found; where our wagons might be dashed to atoms by falling from precipices. A thousand vague and undefined difficulties were present to our imaginations; yet all felt strong for the work, feeling that it was our last. Yet the imagined difficulties were without foundation. Instead of losing our wagons, and packing our cattle; or, as some suggested, as a last resort for the weary, mounting astride of an old ox, and thus making our debut into the valley of the land of gold — we were unable to add a single page of remarkable adventure across the mountains more dangerous than we had already encountered. (17)

Alonzo Delano then met James Beckwourth (whom he called Beckwith, incorrectly), the famous African American adventurer and settler — Beckwourth Pass in the Northern Sierra Nevada is named for him. Not long afterward, Delano experienced a close call:

I had preceded my companions along the border of a deep ravine, and was about fifty rods in advance, when the ravine terminated in a perpendicular wall of rock, hundreds of feet high, around which there appeared to be a craggy opening, or passage. While I was gazing on the towering rock before me, I momentarily changed my position, when the front part of my coat was grazed by something passing like a flash before me. Glancing at the base of the rock, I saw two naked Indians spring around a jutting, and I comprehended the matter at once. I had been a mark, and they had sent an arrow, which grazed my coat, but without striking me. I instantly raised my rifle and discharged it at the flying Indians, and sprang behind a tree. The noise of my piece soon brought my companions to my side, and going cautiously to the rock, a few stains of blood showed that my aim had not been decidedly bad; but we saw nothing more of the Indians. (18)

After this decidedly interesting day, Delano was grateful for “a blanket, supper, and breakfast.” (19) After a day’s rest, Delano continued his journey to what he called “Lawson’s Settlement.” This was actually the settlement of Peter Lassen, for whom nearby Mt. Lassen is named. The tiny community was later renamed Benton City in honor of Thomas Hart Benton, the expansionist senator and friend of Andrew Jackson.

Continuing from Lawson’s Settlement, Delano saw the unmistakable outline of Mt. Shasta as he continued on the trail.

From the brow of the hill we had a charming prospect. The great valley extended many miles before us, and at the limit of vision, perhaps eighty miles distant, a high and apparently isolated snowy peak lifted its head to the clouds, like a beacon to travelers on their arduous journey, and the clear water of the Pitt was sparkling in the morning sun, as it wound its way, fringed with willows, through the grassy plain. The high, snow-capped butte was Mount Shasta; and though it appeared to us to be on a plain at the extremity of the valley, it was in fact surrounded by a broken and mountainous country, far from the course of the river. (20)

It was at this point in his adventure that Alonzo Delano enjoyed what he hoped would be a special feast. After months of poor quality trail food and hurried meals, Delano dreamt of a feast — a beef steak dinner. Near the end of his journey, he enjoyed one — after a fashion.

Feeling an aristocratic longing for a rich beef steak, I determined to have one. There was not a particle of fat in the steak to make gravy, nor was there a slice of bacon to be had to fry it with, and the flesh was as dry and as hard as a bone. But a nice broiled steak, with a plenty of gravy, I would have — and I had it. The inventive genius of an emigrant is almost constantly called forth on the plains, and so in my case. I laid a nice cut on the coals, which, instead of broiling, only burnt, and carbonized like a piece of wood, and when one side was turned to cinder, I whopped it over to make charcoal of the other. To make butter gravy, I melted a stearin candle, which I poured over the delicious tit-bit, and, smacking my lips, sat down to my feast, the envy of several lookers-on. I sopped the first mouthful in the nice looking gravy, and put it between my teeth, when the gravy cooled almost instantly, and the roof of my mouth and my teeth were coated all over with a covering like hard beeswax, making mastication next to impossible.

“How does it go?” asked one.

“O, first rate,” said I, struggling to get the hard, dry morsel down my throat; and cutting off another piece, which was free from the delicious gravy, “Come, try it,” said I; “I have more than I can eat, (which was true.) You are welcome to it.” The envious, hungry soul sat down, and putting a large piece between his teeth, after rolling it about in his mouth awhile, deliberately spit it out, saying, with an oath, that “Chips and beeswax are hard fare, even for a starving man.”

Ah, how hard words and want of sentiment will steal over one's better nature on the plains. As for the rest of the steak, we left it to choke the wolves. (21)

Sacramento

After this less than delectable meal, Delano had his first view of the Sacramento Valley. Finally, after more than six months of dusty, feverish days on the trail he had reached his goal. Delano’s rough draft of his journal shows that his first impressions of the valley less than complimentary, but by the time he published his journal in 1854, he had softened his viewpoint considerably:

After this less than delectable meal, Delano had his first view of the Sacramento Valley. Finally, after more than six months of dusty, feverish days on the trail he had reached his goal. Delano’s rough draft of his journal shows that his first impressions of the valley less than complimentary, but by the time he published his journal in 1854, he had softened his viewpoint considerably:

Ascending to the top of an inclined plain, the long-sought, the long-wished-for and welcome valley of the Sacramento, lay before me, five or six miles distant.

How my heart bounded at the view! how every nerve thrilled at the sight! It looked like a grateful haven to the tempest-tossed mariner, and with long strides, regardless of the weariness of my limbs, I plodded on, anxious to set foot upon level ground beyond the barren, mountain desert. I could discern green trees, which marked the course of the great river, and a broad, level valley, but the day was too smoky for a very extended view. There was the resting place, at least for a few days, where the dangerous and weary night-watch was no longer needed; where the habitations of civilized men existed, a security from the stealthy tread of the treacherous savage; where our debilitated frames could be renewed, and where our wandering would cease. (22)

After a few days rest, Delano and a companion headed south to the newly formed village of Sacramento City, the domain of the imperious John Sutter and his self-styled kingdom of New Helvetia. Delano had a rickety wagon, four dollars in his pocket and a heart full of hope.

His impressions of this new river city were very favorable:

Sacramento City … contained a floating population of about five thousand people. It was first laid out in the spring of 1849, on the east bank of the Sacramento River, here less than one-eighth of a mile wide, and is about a mile and a half west of Sutter's Fort. Lots were originally sold for $200 each, but within a year sales were made as high as $30,000. There were not a dozen wood or frame buildings in the whole city, but they were chiefly made of canvass, strectched over light supporters; or were simply tents, arranged along the streets. The stores, like the dwellings, were of cloth, and property and merchandise of all kinds lay exposed, night and day, by the wayside, and such a thing as a robbery was scarcely known. This in fact was the case throughout the country, and is worthy of notice on account of the great and extraordinary change which occurred. (23)

Delano rested, sleeping outside under the stars, as was now his habit. Quite quickly, he became almost fully recovered from his lingering illness and was eager to join his fellow goldseekers in the search for their elusive golden quarry.

The Gold Lake Fiasco

In 1850, Alonzo Delano joined other goldseekers in the fascinating event known as the Gold Lake Fiasco. Based upon the very suspect claims of a man named Stoddard who said he had discovered a lake ringed with gold nuggets and upon whose waters sheets of thin gold floated like leaves — a magical lake whose Indian inhabitants fashioned fishhooks and furniture out of solid gold. Following Stoddard, Delano and more than a thousand others swarmed the mountains near today’s Downieville in search of the lake. They found nothing, and they confronted Stoddard. “Take us to the lake in the next 24 hours or we will kill you,” the goldseekers said. The next morning they discovered something all right — that Stoddard had disappeared. Delano recalled the fiasco in this way:

In May, 1850, a report reached the settlements that a wonderful lake had been discovered, an hundred miles back among the mountains, towards the head of the Middle Fork of Feather River, the shores of which abounded with gold, and to such an extent that it lay like pebbles on the beach. An extraordinary ferment among the people ensued, and a grand rush was made from the towns, in search of this splendid El Dorado. Stores were left to take care of themselves, business of all kinds was dropped, mules were suddenly bought up at exorbitant prices, and crowds started off to search for the golden lake.

Days passed away, when at length adventurers began to return, with disappointed looks, and their worn out and dilapidated garments showed that they had “seen some service,” and it proved that, though several lakes had been discovered, the Gold Lake par excellence was not found. The mountains swarmed with men, exhausted and worn out with toil and hunger; mules were starved, or killed by falling from precipices. Still the search was continued over snow forty or fifty feet deep, till the highest ridge of the Siérra was passed, when the disappointed crowds began to return, without getting a glimpse of the grand desideratum, having had their labor for their pains. (24)

But Delano, ever the merchant, saw opportunity in disappointment:

Yet this sally was not without some practical and beneficial results. The country was more perfectly explored, some rich diggings were found, and, as usual, a few among the many were benefited. A new field for enterprize was opened, and within a month, roads were made and traversed by wagons, trading posts were established, and a new mining country was opened, which really proved in the main to be rich, and had it not been for the gold-lake fever, it might have remained many months undiscovered and unoccupied. (25)

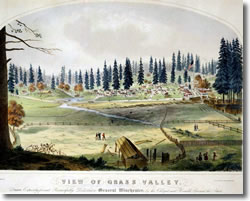

Alonzo Delano did not abandon mining after this incident, but his mining career could be characterized as spotty and unproductive at best. In Nevada County, he worked in underground mines in the Gold Country boomtowns of Grass Valley and Nevada City and spent much time of his working what are called “coyote holes” or “coyote diggins” — short tunnels hollowed out of hillsides. He failed and soon turned back to his original calling — the merchant life. Delano prospered, to use a common phrase of the period, by “mining the miners.”

Alonzo Delano did not abandon mining after this incident, but his mining career could be characterized as spotty and unproductive at best. In Nevada County, he worked in underground mines in the Gold Country boomtowns of Grass Valley and Nevada City and spent much time of his working what are called “coyote holes” or “coyote diggins” — short tunnels hollowed out of hillsides. He failed and soon turned back to his original calling — the merchant life. Delano prospered, to use a common phrase of the period, by “mining the miners.”

He gravitated back to Sacramento, and, after a few months absence, was astonished by the changes in the rapidly growing city:

Sacramento City had become a city indeed. Substantial wooden buildings had taken the place of the cloth tents and frail tenements of the previous November, and, although it had been recently submerged by an unprecedented flood, which occasioned a great destruction of property, and which ruined hundreds of its citizens, it exhibited a scene of busy life and enterprise, paculiarly characteristic of the Anglo-Saxon race by whom it was peopled. An immense business was doing with miners in furnishing supplies; the river was lined with ships, the streets were thronged with drays, teams, and busy pedestrians; the stores were large, and well filled with merchandise; and even Aladdin could not have been more surprised at the power of his wonderful lamp, than I was at the mighty change which less than twelve months had wrought, since the first cloth tent had now grown into a large and flourishing city. (26)