Alonzo Delano: Nomad Denizen of the World

by Gary Noy

Center for Sierra Nevada Studies

The story of Alonzo Delano is a tale of adventure, artistic accomplishment, and hope. It is the chronicle of how Delano became, in his own words, “a nomad denizen of the world.”

The story of Alonzo Delano is a tale of adventure, artistic accomplishment, and hope. It is the chronicle of how Delano became, in his own words, “a nomad denizen of the world.”

The Beginnings

Alonzo Delano was a goldseeker — one of the many thousands who crossed westward across the forbidding American outback in 1849 to reach the glittering possibility that the California Gold Rush offered. Everyone who “westered” during the California Gold Rush era had an experience that was composed of two parts: how they got there and what they did once they got there. For Delano, both elements were remarkable and consequential. He left a trail journal that remains one of the most interesting and useful of any published during the period. Delano’s writings upon his arrival in California became the basis for a new school of literature that came to be known as “California Humor,” a writing style that brought him great popularity and profoundly influenced such writers as Bret Harte and Mark Twain. And his actions during one community’s darkest hour gave the town a profound sense of hope and renewal.

Alonzo Delano was born July 2, 1806, in Aurora, New York, a town that has also been known as Ledyard during its existence. It is located on the banks of Cayuga Lake in upstate New York. Delano was the tenth of eleven children of Dr. Frederick Delano. The Delanos were the descendants of French Huguenots, most notably Phillipe de la Noye, who was Alonzo’s great-great-grandfather and the great-great-great-great-grandfather of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Not unusually for the era, Delano left school at an early age and entered into the life of a merchant at the age of fifteen. This itinerant merchant life led to him to visit many frontier communities in Ohio and Indiana.

In 1830, he returned to Aurora, where he met and wed Mary Burt. Soon afterward they moved to Indiana, and two children were born to Alonzo and Mary — Fred in 1833 and Harriet in 1843 — both probably in South Bend, Indiana.

By 1848, Delano and family had relocated once again and were comfortably situated in Ottawa, Illinois, in the centrally located LaSalle County on the banks of the Illinois River. Delano was prospering as a merchant and was a well-respected civic leader of the community.

Then, in that historic year, there were two momentous occurrences in Delano’s life … gold was discovered in California and Delano was very sick with what was called consumption in those days, a serious respiratory ailment. Delano became afflicted with two fevers — an actual fever and Gold Fever.

The Journey Begins

Alonzo Delano received an interesting medical prescription from his doctor — go west with a wagon train, go to a new locale, and cure what ails you. Some reports filtering back from California had erroneously stated that the entire Gold Country was tropical or partly desert. Unfortunately that led many to believe that the goldfields would be an excellent place to cure lung ailments. And, so, with this odd prescription in hand, Delano began his adventure to the west and set in motion changes that would alter his life, his family’s life, and the circumstances of many in California. Alonzo Delano was 42 years old, sick, traveling alone to an unknown place, over an unfamiliar path to an uncertain fate. As he wrote in his 1854 journal Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings:

Alonzo Delano received an interesting medical prescription from his doctor — go west with a wagon train, go to a new locale, and cure what ails you. Some reports filtering back from California had erroneously stated that the entire Gold Country was tropical or partly desert. Unfortunately that led many to believe that the goldfields would be an excellent place to cure lung ailments. And, so, with this odd prescription in hand, Delano began his adventure to the west and set in motion changes that would alter his life, his family’s life, and the circumstances of many in California. Alonzo Delano was 42 years old, sick, traveling alone to an unknown place, over an unfamiliar path to an uncertain fate. As he wrote in his 1854 journal Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings:

Ninety days previous to the 5th of April, 1849, had any one told me that I should be a traveler upon the wild wastes between the Missouri river and the Pacific ocean, I should have looked upon it as an idle jest; but circumstances, which frequently govern the course of men in the journey of life, were brought to bear upon me; and on the day above named, I became a nomad denizen of the world, and a new and important era of my life began.

My constitution had suffered sad inroads by disease incident to western climate, and my physician frankly told me, that a change of residence and more bodily exertion was absolutely necessary to effect a radical change in my system — in fact, that my life depended upon such a change, and I finally concluded to adopt his advice. About this time, the astonishing accounts of the vast deposits of gold in California reached us, and besides the fever of the body, I was suddenly seized with the fever of mind for gold; and in hopes of receiving a speedy cure for the ills both of body and mind, I turned my attention “westward ho!” and immediately commenced making arrangements for my departure. (1)

Just prior to his departure, he made arrangements with William and Moses Osman, brothers and publishers of the Ottawa Free Trader newspaper, to correspond with them about his journey. These letters and a journal Delano kept were known as the “California Correspondence,” and, along with some other writing done for a New Orleans publication, formed the core of what later became a book on his adventures entitled Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings (1854). Delano’s correspondence carried with it a cachet and an important responsibility — Alonzo was so respected that the residents of Ottawa expected that Delano would give them straight information about the journey, not the embellished accounts that were more common than not.

Farewell to An Old Life

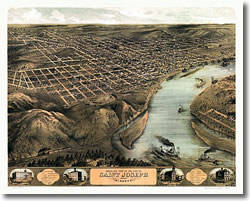

In April 1849, Delano said farewell to his wife and children and headed down the Illinois River toward St. Louis on a vessel called the Embassy. He would not see his family again for six years. Ultimately, he arrived at a major embarcation venue to the west — St. Joseph, Missouri, on the banks of the wide Missouri River. Alonzo’s fellow passengers on the Embassy were filled with hope and enthusiasm.

In April 1849, Delano said farewell to his wife and children and headed down the Illinois River toward St. Louis on a vessel called the Embassy. He would not see his family again for six years. Ultimately, he arrived at a major embarcation venue to the west — St. Joseph, Missouri, on the banks of the wide Missouri River. Alonzo’s fellow passengers on the Embassy were filled with hope and enthusiasm.

There was a great crowd of adventurers on the Embassy. Nearly every State in the Union was represented. Every berth was full, and not only every settee and table occupied at night but the cabin floor was covered by the sleeping emigrants. The decks were covered with wagons, mules, oxen, and mining implements, and the hold was filled with supplies. But this was the condition of every boat — for since the invasion of Rome by the Goths, such a deluge of mortals had not been witnessed, as was now pouring from the States to the various points of departure for the golden shores of California. Visions of sudden and immense wealth were dancing in the imaginations of these anxious seekers of fortunes, and I must confess that I was not entirely free from such dreams…. (2)

Upon arrival at St. Joe, Delano became part of a company led by Jesse Greene. The party was known as the Dayton Company, as many of its members came from Dayton, Illinois in LaSalle County. The Dayton Company benefited significantly from Delano’s financial standing, as he purchased most of the cattle and wagons for the company. He was given the honorary title of “Captain” as a result.

Delano was extraordinarily literate, and almost clinical in his observations, and while many journals of the westward movement are full of hope and humor, Delano’s was also filled with wrenching descriptions of the difficulty of the journey. On the second page of his journal he writes of a tragic occurrence.

A young gentleman, belonging to a company from Virginia, who had indulged in some imprudence in eating and drinking, while at St. Louis, was the subject of attack; and although every attention was rendered which skill and science could give, the symptoms grew worse, and he expired at ten o'clock on the morning after he was taken ill.

It was a melancholy spectacle, to see one who had left home with high hopes of success, so prematurely stricken down; and although he had no mother near him to soothe his last anguish, or weep over his distress, he was surrounded by friends who were ready and willing to yield any assistance to mitigate his pain. Indeed, there was not a man on board, whose heart did not yearn to do something for the sufferer. Preparations were made for his interment; and a little before sunset the boat was stopped, to give us, his companions, an opportunity to bury him.

It was in a gorge, between two lofty hills, where a spot was selected for his grave. A bright green sward spread over the gentle slope, and under a cluster of trees his grave was dug by strangers. A procession was formed by all the passengers, which, with a solemnity the occasion demanded, proceeded to the grave, where an intimate friend of the deceased read the Episcopal burial service, throughout which there was a drizzling rain, yet every hat was removed, in respect to the memory of a fellow passenger, and in reverence to God. How little can we foresee our own destiny! Instead of turning up the golden sands of the Sacramento, the spade of the adventurer was first used to bury the remains of a companion and friend. (3)

Delano’s complete route, except for the very first section, followed a well-worn trail, although Delano had no idea what was facing him.

Across the Plains

After outfitting in St. Joseph, Captain Delano’s party traveled sixty miles north of St. Joe on the Missouri River to Harney’s Landing, where they crossed the wide Missouri. Harney’s Landing was a less commonly used ford than other spots along the Missouri and Delano’s party traveled a much less traveled route in the earliest part of his journey. This was called the Namaha Cutoff and Delano said only one train had followed this route — in the previous four years. Delano considered it one of two great mistaken decisions on the trail, losing much time to those who had crossed at St. Joe. Harney’s Landing does not show on contemporary maps of Missouri. It was named for a Brig General Indian fighter named William S. Harney.

Delano was sick, sick, sick when they bundled him up to cross the river. Delano recounted later how he felt:

Before I got to sleep, I felt strangely. Was there a change in the weather? I could not get warm. I piled on more clothes. I felt as if I was in an ice-house. Ugh! the cold chills were creeping along my back I involuntarily drew up my knees, and put my head under the bed clothes, but to no purpose — I was shivering, freezing, and then so thirsty! — I wanted a stream of ice-water running down my throat. At length I began to grow warm, warmer; then hot, hotter, hottest. I felt like a mass of living fire — a perfect engine, without the steam and smoke. There seemed to be wood enough from some source, but I poured in water till I thought my boiler would burst, without allaying the raging thirst which consumed me. At last the fever ceased, and then, indeed, the steam burst in a condensed form through the pores of my burning skin, and my body was bathed in a copious perspiration, that left me as weak as any “sucking dove.” I had had a visit from my old friends, chill and fever. (4)

Delano would actually spend the first week of the journey lying in a wagon delirious with fever. After traveling this less common route for the first days, Delano’s group finally reached the famous Platte River road. And soon, as the company headed west, Delano was encountering the famous landmarks along the trail.

Such as Chimney Rock, in today’s Nebraska:

The rock much resembled the chimney of a glass-house furnace. A large cone-like base, perhaps an hundred and fifty feet in diameter, occupied two thirds of its height, and from thence the chimney ran up, gradually growing smaller to the top. The height of the whole is said to be two hundred and fifty feet above the level of the river, from which it is between three and four miles distant. It is a great curiosity, and I much regretted that I had not strength enough to visit it. I think it is decaying from the action of the elements, and it is quite likely that the chimney will be broken off in time, leaving nothing but its cone to gratify the curiosity of the future traveler. The hills in the vicinity present a fanciful appearance — sometimes like giant walls, of massive gray rock, and again like antiquated buildings of olden time. (5)

Delano had plenty of company, as many other wagon companies occupied the same route.

Although I speak particularly of our own train, and of the events which came under my own eye, the reader should bear in mind that there were probably twenty thousand people on the road west of the Missouri, and that our train did not travel for an hour without seeing many others, and hundreds of men. For days we would travel in company with other trains, which would stop to rest, when we would pass them; and then perhaps we would lay up, and they pass us. Sometimes we would meet again after many days, and others, perhaps, never. As near as we could ascertain, there were about a thousand wagons before us, and probably four or five thousand behind us. (6)

|

|

Delano passed by Scotts Bluff, Nebraska, and Fort Laramie, in present-day Wyoming, and by June 25, he arrived at Independence Rock, Wyoming, a bit earlier than many who arrived at this location around July 4th, Independence Day.

Near our encampment, and immediately at the ford, stood Independence Rock, a huge boulder of naked granite, forty or fifty rods long, and perhaps eighty feet high. It stands isolated upon the plain, about six miles from the mountains on the right, and three from those on the left. It is not difficult of access on its southern point, and may be ascended in many places on the east. In a deep crevice on the south, is a spring of ice-cold water — a perfect luxury to the thirsty emigrant. Hundreds of names are painted on its south wall, and among them I observed some dated 1836. Fatigued as I was, a hyena might have tugged at my toes without awaking me, for I had paddled through the sun and sand twenty-two miles. (7)

Delano observed the many names carved in the rock and the evidence of many trains, and wished to linger a bit. But the trail beckoned, and he continued onward, westward, always westward.

He passed by Split Rock, Wyoming:

On the north side of the road stood a bare, isolated rock of granite, sloping like a roof, which, though not as large as Independence Rock, was something of a curiosity, from its immense size. In the bare granite range on the right was a mountain rock many miles distant, which resembled a castle with a dome, and it looked like the strong-hold of some feudal baron of olden time; but as we passed on, it soon changed its appearance to a shapeless, broken mass of granite. (8)

Delano commented on the terrain and as he approached and passed through South Pass in the Wyoming wilderness. He was particularly impressed with the abundance of wildlife:

Delano commented on the terrain and as he approached and passed through South Pass in the Wyoming wilderness. He was particularly impressed with the abundance of wildlife:

The face of the whole country from the Black Hills to the South Pass is peculiar and interesting. High table elevations, with flat surfaces; solitary conical mountains, with flattened tops; spurs, like huge embankments for rail-roads or canals, running at angles from the main ranges, may here be seen. Red earth-column buttes seem to rise from the plain — the granite hills often assuming fantastic shapes which cannot be described, with here and there barren sage plains, and ponds of carbonate of soda. These are the general characteristics which mark this strange portion of the world. Antelope and buffalo are very numerous; and lizards and crickets, crawling in vast numbers over the burning sands, are the principal varieties of insect life which the traveler sees. (9)

But Delano’s eye was observant of the human landscape as well. He remarked about how the difficult journey was changing the nature and personal dynamics of the wagon parties.

On leaving the Missouri, nearly every train was an organized company, with general regulations for mutual safety, and with a captain chosen by themselves, as a nominal head. On reaching the South Pass, we found that the great majority had either divided, or broken up entirely, making independent and helter-skelter marches towards California. Some had divided from policy, because they were too large, and on account of the difficulty of procuring grass in one place for so many cattle, while others, disgusted by the overbearing propensities of some men, would not endure it, and others still, from mutual ill-feelings and disagreements among themselves. Small parties of twenty men got along decidedly the best; and three men to a mess, or wagon, is sufficient for safety as well as harmony. (10)