Alonzo Delano: Nomad Denizen of the World

by Gary Noy

Center for Sierra Nevada Studies

… part 3, continued

San Francisco and “Old Block”

Delano established a number of shops and businesses throughout the region. For awhile he even passed himself as an artist of miniature paintings. In his own description, Delano was not talented, or even average in skill, but anything to make a buck. His other business ventures, such as selling vegetables, most notably succeeded in San Francisco. In the booming City by the Bay, Delano reported on the activities of the Vigilance Committee and became a quite well-known figure. But his promising business was reduced to ashes in a massive 1851 fire.

He set his sights on a return to Grass Valley, where he had commercial connections, ultimately establishing his base of operations at that spot. Again, the energetic Delano flourished. Within months, Delano became a leading city of the mining town. He was elected the city’s first treasurer, he became the town’s Wells Fargo agent, and was widely respected for his civic accomplishments.

Delano was also becoming acknowledged for his artistic accomplishments as well — his letters and journals were published to rave reviews. He wrote comic poems and vignettes of gold rush life that were very popular — as popular as the writings of Bret Harte and Mark Twain would later become. His pen name of Old Block was widely known.

He wrote humorous essays and plays — including the play A Live Woman in the Mines, which addressed the fact that women were exceedingly rare in the gold fields. This play is still performed on occasion today.

|

|

Delano’s work was illustrated by the prominent and popular artist Charles Christian Nahl, which added to their popularity. (27)

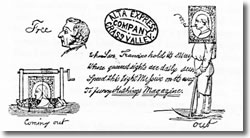

In fact, Alonzo Delano became so celebrated that letters addressed to him in Grass Valley did not even have to have an address — simply a drawing of Old Block would be sufficient, such as one that illustrates this article, addressed to him by his fellow humor writer, George Horatio Derby, known by his charming pseudonym, The Veritable Squibob.

In fact, Alonzo Delano became so celebrated that letters addressed to him in Grass Valley did not even have to have an address — simply a drawing of Old Block would be sufficient, such as one that illustrates this article, addressed to him by his fellow humor writer, George Horatio Derby, known by his charming pseudonym, The Veritable Squibob.

Delano was a father of what came to be known as “California Humor” — satirical social commentary utilizing exaggerated situations. It is a literary style that has influenced generations of writers and performers.

|

|

Alonzo Delano also befriended the other Grass Valley celebrity of the time — the scandalous Lola Montez — even being described, falsely, as the much younger Lola’s private secretary and possible love interest. However, Delano would have a falling out with the mercurial Montez.

Grass Valley and a Devastating Fire

It is at this point that a new phase of Delano’s life would emerge — in the most devastating of circumstances. Grass Valley in 1855 was a prosperous city of 3500. In March 1855, Grass Valley organized as a city, with the first Treasurer being Alonzo Delano, the highly respected Wells Fargo agent. While the new government was destined to be short lived (it was declared unconstitutional in 1856), the new Board of Trustees went right to work and quickly passed sixteen municipal ordinances. The Grass Valley Board of Trustees addressed the issue of fire, a plague that impacted most Gold Rush-era communities. Many towns up and down the Mother Lode had already suffered significant losses due to fire. The Board passed an ordinance requiring every occupant of every house or commercial building to construct a container holding at least fifty gallons of water and to have four fire buckets for each story. This ordinance was never enforced — with tragic consequences. At 11 o’clock in the evening of September 13, 1855, a fire broke out in the United States Hotel on Main Street and quickly spread. Cries of “fire” echoed through the lonely streets. And soon the population was battling the rapidly growing blaze. In their 1880 History of Nevada County, authors Thompson and West described the ensuing chaos:

All was confusion; the flames were crackling and roaring, licking up the tinder dry buildings in their pathway, and all the undirected efforts of the excited people were futile to stay their onward march. Buildings were pulled down, buckets of water by the hundreds were thrown upon the burning houses, wet blankets and other devices were resorted to, but to no avail, for the frame buildings, dried in the long summer sun, burned too fiercely for the flames to be subdued. All night they fought with tireless energy, and never ceased the struggle until the flames expired for want of food to live upon. (28)

The destruction was enormous. More than three hundred buildings were destroyed in an area covering thirty acres. In the downtown business district only two structures escaped. Every hotel and boarding house was ruined. Residents believed they had lost their savings and important documents to the fire. All seemed hopeless. Contemporary records indicate that the loss of property was valued at $400,000 — in today’s money; this loss would be $8.5 million. The actual loss figure is believed to be much, much higher. It is at this moment that Alonzo Delano enters to save the day and the town.

Among Delano’s writings was a description published in 1856 in Delano’s Old Block's Sketch Book of the devastating fire. Delano wrote glowingly of the calmness and determination of the townsfolk: "On the eventful night which laid our town in ruins, which left us no cover for our heads but the blue vault of Heaven; ... did you hear one word of wailing - one single note of despair? No, not one.” (29)

Delano modestly failed to inform his readers that he had been instrumental in the town's recovery. One of the few items to survive the blaze was the Wells Fargo vault. As the town still smoldered, a curious incident occurred. Quite dramatically, before the crestfallen residents of the ruined town, Alonzo Delano wheeled a tiny shed to the location of his now-incinerated Wells Fargo Office, near the epicenter of the conflagration. Delano posted an “Open for Business” sign and this crude structure would serve as a temporary office. The warm-to-the touch, ash-covered vault was unsealed, and many of the town’s important documents and currency were inside — untouched by the flames. Delano gave hope to the weary population that the devastated community could rebound. And they would never forget.

Delano’s Later Years

Alonzo Delano’s family would finally join him in Grass Valley at this juncture. Delano’s daughter Harriet would arrive in 1856, but his wife Mary would stay in New York to care for their invalid son Fred who would die in 1857. Mary then joined her husband. Grass Valley rebuilt and Delano continued to be a leader in the community and a symbol of its renewal.

|

|

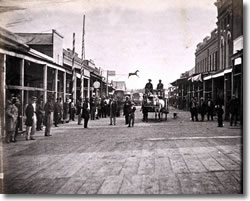

The town continued to grow and suffered additional, but less devastating, fires. Perhaps part of the reason that Grass Valley was plagued by fires is that the streets were wooden planks — the town was literally carpeted with flammable fuel. Delano briefly left the town in 1866 for an unhappy duty. His daughter Harriet became mentally ill and Delano accompanied her back to an asylum in New York, via Nicaragua. He recounted this sad journey in his humorless so-called “Nicaragua Letters” which were published in a local Grass Valley newspaper. (30)

Returning to Grass Valley after this difficult experience, Delano continued to prosper — investing in quartz mining interests and starting a bank. His wife Mary died in 1871. Delano remarried in 1872. His second wife was Maria Harmon, a vivacious young woman twenty years younger than Alonzo.

Sadly the union would be short-lived. In September 1874, Delano succumbed after a brief illness. Grass Valley mourned the loss of the man who saved their community. The whole town, including the mines, shut down on the day of his funeral and, according to accounts, nearly the entire community population attended the funeral and burial at the city’s Greenwood Cemetery.

And so ended the remarkable life of Alonzo Delano, nomad denizen of the world. But his memory lives on in his writings and in the thriving Gold Country town of Grass Valley, the town that he saved in 1855.

Endnotes

- Alonzo Delano, Life on the Plains and Among the Diggings (Auburn and Buffalo, New York: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1854), pp. 13-14. This journal presented Delano’s trail diary organized chronologically (dates for entries are listed in citations below) and additional undated writings in the last chapters of the book. Delano edited his original rough draft for this volume and for the most part it is faithful to his initial observations and intent.

- Ibid., April 2-3, 1849, pp.14-15.

- Ibid., April 3, 1849, pp.15-16.

- Ibid., April 4, 1849, p.19.

- Ibid., June 8, 1849, pp.70-71.

- Ibid., June 21, 1849, pp.94-95.

- Ibid., June 22, 1849, p.98.

- Ibid., June 25, 1849, p.104.

- Ibid., June 28, 1849, p.111.

- Ibid., June 29, 1849, p.117.

- Ibid., July 1, 1849, p.121.

- Ibid., July 4, 1849, p.125.

- Ibid., July 24, 1849, pp.152-153.

- Ibid., August 4, 1849, p.166.

- Ibid., August 16, 1849, pp.180-181.

- Ibid., August 17, 1849, pp.184-185.

- Ibid., August 25, 1849, p.201; August 26, 1849, p.201.

- Ibid., August 26, 1849, p.203.

- Ibid., p.204.

- Ibid., August 31, 1849, p.210.

- Ibid., September 12, 1849, pp.224-225.

- Ibid., September 17, 1849, pp.230-231.

- Ibid., undated, probably in November 1849, p. 251.

- Ibid., undated, probably May 1850, pp.332-333.

- Ibid., p.333.

- Ibid., undated, probably in June 1850 pp.288-289.

- Alonzo Delano, A Live Woman in the Mines (New York: Samuel French, 1857). Charles Christian Nahl became one of the best-known chroniclers of Gold Rush California through his illustrations. An excellent book on his life and work is Moreland L. Stevens and Marjorie Arkelian, Charles Christian Nahl: Artist of the Gold Rush (Sacramento: E.B. Crocker Art Gallery, 1976).

- Thomas Hinckley Thompson and Albert Augustus West, History of Nevada County (Oakland, CA: Thompson and West, 1880), p.66. This history was reissued in 1970 in Berkeley, California by Howell-North Books.

- Alonzo Delano, Old Block’s Sketch Book, or Tales of California Life (Sacramento, 1856), p.41. This book was reprinted in an excellent edition in 1947 by The Fine Arts Press of Santa Ana, California.

- Alonzo Delano wrote the “Nicaragua Letters” in 1866 and they were reprinted in the Grass Valley Union newspaper throughout that year.