Field Trippin'

by Joe Medeiros

Professor Emeritus, Biological Sciences Dept.

In today’s technological world of virtual reality, is there even a reason to go out into the field? Can’t we do all of our exploring and decision-making from the comfort and safety of our own home or office or laboratory? Haven’t we learned enough about “out there” to enable us to completely understand it? And can’t we just manipulate it (nature) from our computers? And, what exactly is “the field” anyway?

Field trips have been utilized by humans around the world for generations. But they began quite differently. Perhaps they would first be considered “explorations”, when transportation was primitive and much (most) was unknown about the regions to be explored. What adventures these must have been!

Explorer David Douglas

As a botanist, I think often of the intrepid Scottish explorer, David Douglas (1799-1834) who collected plants and other specimens in North America for England. With no formal roads (only primitive and rudimentary trails made by natives), no hotels/motels, no REI where you could outfit yourself with the latest camping gear, and no Cabela’s where you could buy your hunting equipment, you just set off with very crude maps (no AAA, no GPS) and a compass with the instructions to “get out there and gather important information about such-and-such a place.”

While Douglas was attempting to locate new and interesting or important species (or mineral deposits, or other natural resources), he also had to vigilantly look over his shoulder for potential dangers – from rattlesnakes and grizzly bears to P.O.’d Indians who didn’t approve of his trespassing into their tribal hunting territories – all this while also negotiating raging rivers and scaling perilous cliffs. Such adventures by Douglas introduced the world to scores of new conifers (Douglas-fir, Pondersosa pine, etc.) and oaks as well as myriad flowers previously unknown to Europeans. These adventures, while extremely productive, also rendered Douglas exhausted and haggard. Before he died, associates said he looked like a worn-out old man (he had just turned 35). David Douglas introduced hundreds of new species, landscapes, and cultures to the world but he also paid dearly for the honor of doing so – those were “the good ol’ days?”

Fond field trip memories

When retired biology profs like me think of past field trips, our minds wander happily to national parks, wilderness areas and similar wild places. We think of every conceivable biome, aquatic and terrestrial, where natural species function normally within their physical environment – wetlands, deserts, forests, tundra, grasslands and other ecosystems at any latitude or altitude. We think of such places as rich natural sources of evidence and information that reinforce the principles we teach in our classrooms. Feeling inadequate by simply drawing diagrams and showing slides (from previous field trips) we willingly head out into the field to expose our students to reality. Such reality is evidence – proof – of specimens, species and processes that make our Earth the special place that it is. Excepting for those times when we come home drenched by the surprise storm or frozen by unseasonal weather, we normally come home enriched with collections, photographs, sketches, notes, and memories of marvelous places and the wonders of nature. And then we put them to work!

It is the field that enables the scientist to test the hypotheses and theories generated in the laboratory. It is the field that enables us to count, measure, weigh, photograph, analyze, and otherwise do what scientists are supposed to do: study, experiment and test – repeatedly – to reassure ourselves of our conclusions and to look for flaws in our arguments. So, back again to “what exactly is the field?” Without being able to precisely define it, perhaps the field is the dynamic source of interest, information, and inspiration for the human mind. It is where Earth’s biodiversity interacts and responds with itself and the physical environment. It is not static, but dynamic. We can observe it changing, adapting, and evolving. Every time we visit the field we find something new – some new tidbit of information, some new item of intrigue, or some inspiration that will grow and mature into another valuable human treasure.

The field prepares us

It is also the field that enables us (or requires us) to observe the functions of nature – to carefully study species, populations and ecosystems as well as physical phenomena from volcanoes and glaciers to hurricanes and tornados. By making such careful observations we can, in many cases, predict problems that may vitally affect our own species – from coral reef die-off to volcanic eruptions and earthquakes. There is no doubt that Earth’s precious ecosystems and processes are now compromised – and we won’t be able to save it (or ourselves) if we don’t know the names of all the players, how they interact with each another, and how we may be negatively affecting our one and only home.

Human explorations and field trips have continued long since they began –always with a spirit of adventure and the quest for knowledge. They have enriched our every human interest and spirited the understanding of science, art, history, music, and well, you name it! What if Paul Simon hadn’t taken a field trip to a few southern African nations and come home with the musical inspiration to create the marvelous album “Graceland?” What if Darwin hadn’t accepted the position of naturalist on H.M.S Beagle to be forever inspired by the species, both living and extinct, that he saw and the processes (glaciers, volcanism, earthquakes, etc.) that he observed and experienced?

John Muir, field tripper

Certainly John Muir is California’s most famous “field tripper.” His countless days in Nature (he normally capitalized the word) from the swamps of the everglades to the high Sierra and the glacial fiords of Alaska, were his constant sources of inspiration. He wrote tirelessly, recording the science of his excursions and then again in the magical prose that made him famous. Whether he was describing his observations of glacial striations on the granite domes of Yosemite or arguing for the protection of America’s magnificent conifer forests, he deftly wove his field experiences into the fabric of his works.

He worked very hard, both in his fruit orchards and in his “scribble den” in Martinez. But everyone knew, especially his beloved wife, Louisa, that if he were ill from a winter cold or exhausted from the continuous labor of writing, that his salvation existed outside – in the wilderness. I only went out for a walk, and finally concluded to stay out till sundown, for going out, I found, was really going in. (from the unpublished journals of John Muir – Linnie Marsh Wolfe, 1938)

Muir also reminds us to:

Camp out among the grass and gentians of glacier meadows, in craggy garden nooks full of Nature’s darlings. Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves. (from Our National Parks, 1901)

Head out!

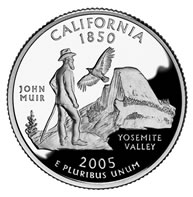

So, whenever you find a new California quarter – the one with John Muir and Half Dome minted upon it – then put it in your pocket (and some bread and tea in your knapsack) and head “out” – go in any direction where wildness appears to still have a foothold – and make yourself available to the inspiration of the field.

Take some binoculars and a few field books (birds, wildflowers, trees, bugs, etc.) and a magnifying lens. Spend some of your life’s precious time investing in your soul and spirit and remind yourself that the best things in life are, in fact, free – and they desperately need our care and protection.