We Are Family: Human Evolution Redux

Jennifer Molina-Stidger

Professor of Anthropology, Sierra College

Learning about family members we are related to and/or descended from is a pursuit that many of us have taken up as a hobby, by building family trees, oral histories and recording anecdotes from our elder family members. The field of paleoanthropology draws on that same interest when it comes to learning the history and prehistory of the ancestors and relatives of modern humans. To take this analogy a bit further, much like Aunt Peggy being reluctant to allow a relative a relegated spot in the family genealogy (“Norma,” she says, “was only a relative by marriage, after all …”) this exciting field of science is also fraught with controversies and less-than-convivial scientists.

Given the serendipitous nature of most initial fossil finds, we might expect a little more humility in the case of those lucky enough to behold them. Yet, with new finds, new analyses and new perspectives, fossil finds (and the paleoanthropologists who found them) are likely to be reshuffled, possibly to a “side branch” of the human line, that is, not a direct ancestor to humans. The reason for this contentious state of the field is that the record is always changing. Our history is much more difficult to piece together than with faded old photographs—the condition of remains so fragile and friable that we cannot conceivably dig them out of the old brown cardboard box we have been meaning to put into albums.

Such extreme fragmentation influenced the long wait scientists made for the detailed description of the remains of Ardipithecus ramidus—found in 1994, provisionally included in our family tree, and then relegated to the information “storeroom” for 15 years. The details of the fossils revealed in Science (October, 2009) currently have experts in an afterglow over the recent re-birth and exciting media blitz. This may very well be the calm before the storm as questions as to the appropriateness of her placement on the human line are sure to follow. Why the hullabaloo?

The Root of the Problem

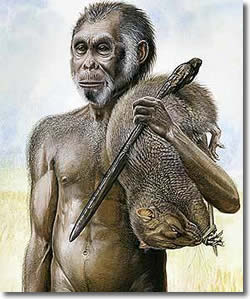

This documenting, revising, revamping and rediscovering is the very nature of scientific inquiry. The recent Scientific American article, “Rethinking ‘Hobbits’: What They Mean for Human Evolution,” (November 2009) provides another example of the scientific process in action. The Homo floresiensis fossils recovered in 2003, and affectionately nicknamed ‘Hobbits,’ have been reanalyzed and found to demonstrate a mix of features that are in some ways human-like and in others more like an ancestral group. This shakes up our earlier notions by suggesting that migrations out of Africa may have taken place much earlier than previously documented. Enter grand speculation of boat construction, geographical pathways, and island rule phenomena.

Does this boggle the record, yes? Is this cause for alarm? No. This is science.

In spite of the controversy over who belongs where on the line leading to humans, the underlying causes of evolution are something we can all agree on. At its root, evolution refers to change over time. Non progressive, the varied characteristics resulting from change are at the mercy of transitions in nature. Some features fit and some do not depending upon the environment. In order to look at these adaptive features and to study our family tree, I have chosen a few of my favorite taxa—those that demonstrate exceptional features biologically—the most extreme, extraordinary and elegant members of the hominid fossil group.

Before Lucy

She may be infamously associated with the human line, but Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis) wasn’t the first or (gasp!) the most interesting of the lot of them. She did, though, bring a kind of celebrity status to the field. This status has burgeoned into even today’s media. Witness the prime time (albeit short-lived) attempt at presenting early humans to the general public in the sitcom “Caveman” and the fabulous “so easy even a caveman could do it…” commercials which blustered through ugly human stereotypes.

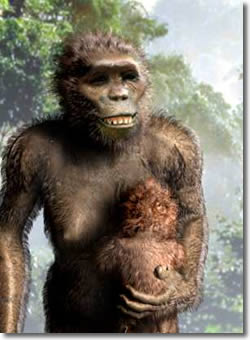

Of newly gained famed, the 700,000 years earlier-than-Lucy Ardi, (short for Ardipithecus ramidus) demonstrates the transitional features seen in Lucy and her contemporaries, but exhibit these features closer to the time when humans shared a common ancestor with living chimpanzees. With the fortunate recovery of fairly complete skeletons, this mosaic of features demonstrates both clear bipedal (two-legged) walking as well as adjustments for accessing the trees by climbing.

Such a mix of features is entirely appropriate for petite (roughly 4 feet tall) groups of individuals skilled at escaping predators, and moving efficiently on the ground. Cranially, Lucy, Ardi and the breadth of these earliest root forms have brains so small they echo the sizes of living apes. And, with the extrapolations for behavioral complexity, one could justifiably nickname them all “bipedal apes.” Though they appear to be on the line to being human, they are most certainly, a distant relative.

Veggie Burger, Anyone? The Diet of an Evolutionary Loser

Highly specialized forms of australopithecines emerged on the hominid scene 2.5 million years ago. With their acute adaptation to diet, I like to characterize these robust australopithecines as extreme vegetarians. In fact, upon reconstructing Australopithecus boisei (a member of this robust line) Louis Leakey, called him “nutcracker man” due to boisei’s impressively powerful jaws, teeth, and muscle attachment sites. Our very distant, robust relatives demonstrated their immense proportions in dentition and skulls only. Their body proportions in other ways were quite “normal” that is, in line with other forms living at the time.

Tied to a diet of veggies, nuts and roots, they were at the mercy of nature to afford them the copious amounts they needed in order to acquire enough calories to survive. It is this vegetarian lifestyle that is presumed to have exacerbated their downfall, outcompeted by other forms living at the time (maverick hominids that extended their diet to include meat when possible and ingeniously accessing bone marrow). But the poor robust australopithecines, tied to their jaws and teeth, and without evidence for accessing high fat, high calorie foods, appear to have eventually died out in times of scarce resources.

Cougar On the Prowl? A First Time for Everything

I have been enamored with the skeletal remains of a young man since we first met. This young member of Homo erectus died at a very young age (roughly 13 as corroborated by different age estimation techniques). Nicknamed after a Kenyan riverbed in the area in which he was found, Nariokotome had achieved a staggering modern height of 5’ 6” at his time of death. Long, lean and strong, his physique is the ideal hot body—forgive me, body well adapted to the heat. This nearly complete skeleton has given valuable information about the lives of Homo erectus including, phases of growth indicated by skeletal and dental development, pelvis size and estimates for fetal development, rib cage size and rudimentary speech sounds, and long appendage and trunk sizes relative to his warm climate.

I have been enamored with the skeletal remains of a young man since we first met. This young member of Homo erectus died at a very young age (roughly 13 as corroborated by different age estimation techniques). Nicknamed after a Kenyan riverbed in the area in which he was found, Nariokotome had achieved a staggering modern height of 5’ 6” at his time of death. Long, lean and strong, his physique is the ideal hot body—forgive me, body well adapted to the heat. This nearly complete skeleton has given valuable information about the lives of Homo erectus including, phases of growth indicated by skeletal and dental development, pelvis size and estimates for fetal development, rib cage size and rudimentary speech sounds, and long appendage and trunk sizes relative to his warm climate.

Though Nariokotome was a representative of African Homo erectus, other members of the taxa were among the first found ‘Out of Africa.’ This migration represents a pivotal point in behavior among our relatives. This first is only one of many which we can tie to this group: First use of handaxes, a sophisticated all-purpose tool type which took new kinds of skills to construct; first record of harnessing fire in Kenya; and first move into cold climates necessitating reliance on culture in addition to biology.

Possibly the greatest first though was an amazing leap into brain sizes roughly 50% larger than their immediate predecessor, Homo habilis. With a larger brain and large modern-sized bodies, their diet must have been largely supported by consuming meat and/or cooking food (an idea currently under investigation by Richard Wrangham and associates). Well suited for nearly any environment, Homo erectus had staying power—as a group they had the longest temporal range of any other hominid, including modern humans.

Hefty Honies

Sure to be the butt of a joke or two in your lifetime, the Neandertals are used to their miserable status among our relatives. What if your name was consistently MISPRONOUNCED through your life? Jen? Meet “Jan.” Shelley? Meet “Shelby.” Neandertal? Meet “NeanderTHal.” Like nails on a chalkboard, we have historically anglicized our contemporary brethren’s name.

Sure to be the butt of a joke or two in your lifetime, the Neandertals are used to their miserable status among our relatives. What if your name was consistently MISPRONOUNCED through your life? Jen? Meet “Jan.” Shelley? Meet “Shelby.” Neandertal? Meet “NeanderTHal.” Like nails on a chalkboard, we have historically anglicized our contemporary brethren’s name.

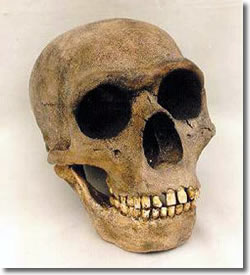

Originally recovered in a German Valley—Neander Valley—“thal” is pronounced “tal” in German. To correct this nomenclature wrong, most writings now represent them simply as Neandertal (as I am doing here) in the hopes of giving these folks just a little dignity.

The gorgeous Neandertal physique is one that many anthropologists discuss in only reverent tones. British females of the 19th century in their finest petticoats, layers of lace and rich fabrics make nowhere near the statement made by the array of physical features exhibited in the classic Neandertal physique. Their brains are massive, indeed more massive than humans living today. And this, in line with large well worn dentition, huge noses, thick, arched brow bones, and boney bun on the back of their skull, gives them a look of a rough, tough and don’t-touch-the-goods kind of human. And that is only part of their extreme physiology.

As the well built Nariokotome demonstrated an African heat adapted body, the Neandertals are easily their cold weather Eurasian counterpart. They were short (roughly 5’ 4” for males), stocky (lower arm and leg bones abbreviated relative to their upper bones), and robustly built with thick bone shafts, and in some cases bowed bones due to extreme muscular stress. Their hands and fingertips were like small saucers and demonstrate thick crests from physical use. This extreme physique is found in both males, females and in part, children. Looking at them from a modern human perspective we can easily see the similarities between us.

The more interesting question is how did early humans look at them? Human enough to associate with? Human enough to mate with? The latter and more vexing question is one that is difficult to answer, though through many genetic examinations seems to be, if we DID mate, we did not produce offspring with them. Fair enough. But on a cold, lonely winter night, who better to cuddle with than a large stout human and the skins from a recent kill (proficient hunters they were!)?

Brutish physique? Yes. Brutish behaviors? No. Some of the most notable among them include placing their dead into intentional burials and compassion for one another. In Iraq, one old, weathered and worn skeleton exhibits a missing arm, virtually no chewing area left on his teeth, and extreme osteoarthritis. How can you explain his successfully reaching elderhood at 40 years other than with fellow folk watching out for him? These are only two of the many interesting behaviors reconstructed from the Neandertal fossil record. With a new name, and a new perspective on these robust rogues, we move to those who we can sufficiently call our direct ancestors.

Swagga Like Us: Home Sapiens Sapiens

Genetic, fossil and archaeological evidence all point to the same cradle in which we grew, Africa. Successfully spreading into all pockets of the world, the most striking aspect of this global distribution is the very nature of our similarities. In less than 170,000 years we have evolved into quite variable looking beings but are still so similar that arbitrary group differences are not noticeable at the genetic level. Not only do we all come from the same bushy tree, modern humans quite literally come from the same, very small branch.

This point cannot be overemphasized: humans, while appearing different, are staggeringly similar to the point where boundaries (“races” [to use the word relegated to the rubbish heap by many]) have no detectable biological value. But cultural and behavioral variations are where human differences become exponential. It is only with modern humans, due in part to their recency, that we get the full picture of what it means to be human.

For most of the preceding taxa mentioned here, the emphasis in biology and culture was on survival—developing accommodating behaviors and physique in a way that over time, allowed us to fit in our varied niches. When studying the record of modern Homo sapiens sapiens though, a new expressive pattern emerges. We are still climatically proportioned depending upon our environment, but regardless of where we look, we find evidence of enrichment and an emphasis on beauty…despite there being no consensus on exactly what those beauty standards are.

Creative Humans

In the paleoanthropological record, the first consistent evidence exists in Africa, where we would expect to find it—ostrich egg bead shells made by humans 70,000 years ago. The unparalleled beauty and infamy of the cave paintings and art during the Upper Paleolithic in Europe is another phase of expression which gives us pause to think about the mind of our ancestors and why they spent time and energy decorating themselves, their dead, and their living spaces. Why the creative explosion exists with the human line and no one else is a question that many have tried to answer. Our large brain sizes can account for some of this, but I am partial to the way Richard Klein and Blake Edgar characterize it as a possible genetic change that causes “the mind’s big bang” (The Dawn of Human Culture, 2003).

How do humans manifest our expressive beginnings today? It depends on where you look and who you ask. Some construct three story palatial apartments. Others use lip disks to enhance sexual appeal. There is simply no end to what humans can do to modify themselves or their environment. We no longer have to evolve to fit our niches; we can (in part) change our niches to fit us.

Of course, this ability has surpassed anything our predecessors could have imagined and has brought a new burden upon us. The themes our predecessors dealt with are still here: competition, resource availability and environment. But this time, as opposed to millions of years ago, the evolutionary process is largely influenced by the decisions we make. Has this made our lives easier than Ardi and Lucy, struggling to make sleeping nests above ground? Or more difficult, like the Neandertals of yesteryear learning how to cope with glacial climates?

We just have to find the best way to use our (now) arsenal of tools to honor our ancestors who put us (bipedally) on the right path.