The California Bandit and Yellow Bird:

The Story of Joaquin Murieta and John Rollin Ridge

The following is the story of the legend of Joaquin Murieta, the celebrated bandit of the California Gold Rush, and the author credited with creating the myth of Joaquin, John Rollin Ridge of Grass Valley.

Yellow Bird

His name was Cheesquatalawny. He lived in Grass Valley. He died young at the age of forty, but what he did changed American popular culture to this day.

In the quiet Greenwood Cemetery, near Lyman Gilmore School, there is a row of markers for the Ridge Family. Most prominent among them is the stone for John Rollin Ridge, one of the most interesting and influential figures of Gold Rush California history.

Born a Cherokee

John Rollin Ridge was the son of a powerful Cherokee family. He was born in 1827 in the Cherokee Nation, near today’s Rome, Georgia. His native name was Cheesquatalawny, which translates into “Yellow Bird.”

John Rollin Ridge personally experienced the most traumatic moments in the tribe's history. In 1830, the Indian Removal Act accelerated the removal of Cherokees from their homes in the Southeast. The Cherokees resisted, but there were divisions within the tribal community as to how to proceed in the future. Federal officials exploited these disagreements. In 1835 the government convinced twenty-one Cherokees, including John Rollin’s grandfather, Major Ridge, and John Rollin’s father, John Ridge, to sign the Treaty of New Echota. The treaty provided for the removal of the tribe to the West and for the abandonment of all Cherokee lands east of the Mississippi. Some Cherokees supported the treaty, while others felt it was a betrayal. A portion of the Indian Removal, in which thousands of Cherokees died enroute to Indian Territory (today’s Oklahoma), came to be called “The Trail of Tears.”

Ridges Murdered by Cherokees

Conflicts about removal within the tribe intensified following the treaty. Within months of removal, the tensions burst into violence. In 1839, Major Ridge and John Ridge were murdered by other Cherokees. The 12-year-old John Rollin witnessed his father’s assassination.

John Rollin Ridge left Indian Territory immediately and went to Arkansas, where he lived for four years. In 1843, young John Rollin was sent to Massachusetts for schooling. He returned to Arkansas in 1845 and began law practice. John Rollin was particularly interested in Cherokee politics and closely followed the developments within the tribe. On one occasion, he expressed a desire to avenge the deaths of his father and grandfather.

In 1847, he married Elizabeth Wilson, a white woman he had met in Massachusetts, and one year later, the couple had their only child, Alice Bird.

First novel written by a Native American

John Rollin’s involvement in tribal politics strengthened. He grew increasingly passionate, and, in 1849, his passion boiled over into bloodshed. John Rollin killed David Kell; a Cherokee that he believed was one of his father’s assassins.

Largely to escape prosecution, John Rollin fled. In 1850, he arrived in California, during the early days of the California Gold Rush. In 1852, Elizabeth Wilson Ridge and Alice Bird made the long journey to the gold fields by way of the Isthmus of Panama to join him. From 1852 to 1864, John Rollin and his family lived in six different California communities, including Sacramento and San Francisco.

After briefly working as a miner, John Rollin Ridge gained a reputation as a writer of note. He wrote poetry (most notably the poem “Mt. Shasta”), but mostly became known as a newspaper editor, reporter and columnist. In 1854, he would write a novel about a celebrated California bandit. It is generally considered to be the first novel written by a Native American and the first novel published in California.

But … more about that in Part Two.

Editor and a Sacramento Bee Founder

From 1857 to 1862, Ridge worked as an editor for several California newspapers, including the California Express, the National Democrat, the San Francisco Herald, and the Red Bluff Beacon. Ridge is also considered to be one of the founding members of the Sacramento Bee.

Not surprisingly, John Rollin wrote extensively about Native American politics. Surprisingly, he was often scathing toward Native Americans. He disagreed with the notion that Indians should remain independent from government control, believing that the federal government provided necessary guidance and assistance to the tribes. John Rollin often ignored, perhaps deliberately, the abuses suffered upon natives by the government. He felt California Indians were inferior to other natives and supported policies that stripped California natives of their lands and rights.

In his earlier days, John Rollin had been a slaveowner and he found himself sympathetic to the conservative faction of the Democratic Party that supported slavery and its extension to California. With the advent of the Civil War, John Rollin’s writings were a study in contradictions. He supported retaining national union at all costs, but he also protested the election of Abraham Lincoln and was favorable toward the Confederacy.

Grass Valley Newspaper Owner

In 1864, John Rollin Ridge and family moved to Grass Valley. He purchased an interest in the Grass Valley National newspaper. He was co-editor with W.S. Bryne. In 1866, Bryne would buy the Grass Valley Union.

John Rollin Ridge and his family lived in a house on Church Street in Grass Valley. Ridge worked as Editor of the National until his death in 1867. In 1866, he briefly traveled to Washington, D.C., as part of a Cherokee delegation hoping to annex the tribal region into the Union as a state. The effort failed and Ridge returned to Grass Valley. He fell ill and died on October 5, 1867. In his October 8th obituary, it was written: "As a writer probably no man in California had a wider and better reputation than John R. Ridge. He possessed a good education had a clear and vigorous mind, was well up in classical lore; and in the possession of these essentials to journalistic distinction it is not surprising that he was professionally successful. With more energy and with stronger aspirations to place his name among the highest literary lights he might have added many volumes to the purer and better literature of the time....He wrote with ease, and as is generally the case with genius, sometimes carelessly…. His remains were yesterday interred in Greenwood Cemetery near this place, his funeral cortege being a very large one...."

Today, John Rollin Ridge rests in final slumber next to his wife; his daughter; his brother, Andrew Jackson Ridge; and some in-laws.

Tree in His Honor Still Stands

In 1876, his widow Elizabeth planted a red maple tree at the corner of School and Neal Street in honor of her husband. The tree came from the battlefield at Gettysburg. It still stands proudly, although it was seriously damaged by a powerful January 2005 storm.

However, John Rollin Ridge lives on through the impact of his stories of Joaquin Murieta, the legendary bandit hero of the California Gold Country. The mythology surrounding Joaquin Murieta stubbornly refuses to expire. Throughout the Mother Lode, his name is still invoked. Sprinkled throughout the region are plaques, inscriptions, and markers recounting the prodigious feats of Murieta, “our” Joaquin. And his legend began with John Rollin Ridge.

“I am Joaquin!”

He was crafty, generous, vindictive, heroic, and remarkably cool under pressure. He was kindly benefactor and cold-blooded killer. He was a man of startling handsomeness and bravado. He was a stealthy avenger, a resourceful escape artist, loyal friend of the downtrodden, and swashbuckling defender of a lost culture. He was real—flesh and blood—his supporters steadfastly proclaimed, while his detractors sniffed that he was the purest fantasy—the creation of John Rollin Ridge’s feverishly romantic imagination. He was Joaquin Murieta, legendary bandit hero of the Gold Country.

Seemingly, Joaquin was everywhere.

Saw Mill Flat, outside the Southern Mother Lode town of Sonora, boasts of being the location of Joaquin’s first homestead upon arriving from Sonora, Mexico, in 1850. Down the road in Murphys, they still tell the tale of how the brave young Murieta swore revenge on the Anglo hooligans who tied him to a tree, beat him bloody and senseless, and then killed his half-brother and raped Joaquin’s girlfriend Rosita. A few miles away, in San Andreas, the story is of Joaquin’s miraculous bulletproof vest, constructed for him by a sympathetic French argonaut. Joaquin was grateful but practical—to test its effectiveness, he made the Frenchman wear the vest while Joaquin shot at him. In Hornitos, they point to a tunnel supposedly used by Murieta in an escape from heavily armed pursuers. Miles away in Volcano, it is claimed that there once was a well-hidden treehouse that secreted the elusive public enemy as tired lawmen rested below him. Dozens of towns claim that Joaquin was here—Joaquin escaped here—Joaquin slept here—Joaquin distributed his loot here—Joaquin. Joaquin. Joaquin.

Did He Really Exist?

Did it actually happen? It is known that in 1853, a man who was called Joaquin Murieta was killed by a hired gunman.

But ... was this the legendary Joaquin? And how much of this tale is fact? How much fiction? It is here that the historical paths diverge.

There are a handful who claim that every incident, every nuance is true, all true. Some admit that the facts may have been fudged a mite, but the skeleton of truth is secure. A few historians acknowledge that some facts are in the historical record, but, for the most part, the story of Joaquin Murieta is an exaggeration. Many scholars believe that the Murieta tale is myth—an entertaining yarn constructed of whole cloth, smoke and mirrors. This latter view is now the predominant historical interpretation.

However, those who argue that the Murieta case is a mixture of fact and folklore offer the following evidence.

Taxes, Crime and Thieves

In early Gold Rush California, it is indisputable that the clash between the once dominant Californio Latino culture and the newly arrived Anglo-American gold miners intensified. In the wake of the 1850 Foreign Miners’ Tax (which required Latinos and other non-English speaking immigrants to pay $16 a month) and the often wholesale expulsion of Californios and Mexicans from the gold fields, land pirates began preying on the mining communities. While many of the outlaws were known to be of European heritage, the majority appear to be Latino. Crime increased dramatically and fear mounted among the good citizens of the Mother Lode.

By 1852 and 1853, the Southern Mines were troubled by a number of thieves. Most of them were called or claimed to be named Joaquin. However, the last names varied—Valenzuela, Carillo, Botilleras, Ocomorenia, and Murieta. They were all mobile, all deceptive, all elusive, and all bothersome. It was difficult, if not downright impossible, to determine which Joaquin had committed a crime. Authorities frequently reported that the criminal was often identified only as “Joaquin” by those interviewed at the scene.

California Legislature Hires Ranger Harry Love

What to do? The Mother Lode mining communities were crying for the immediate apprehension of this wily criminal (or criminals). In May 1853, the California legislature responded by hiring gunman and former Texas Ranger Harry Love to capture the outlaw Joaquin—no last name specified. Dead or Alive. The legislature had debated five different full names, but decided on instructions that used only the generic name of Joaquin. As a reward, the state government offered Love and his twenty member posse a $5000 reward and $150 monthly stipend for all involved. This was a huge sum of money in the days when a few hundred dollars was considered an excellent annual income, and a lot of cash even considering the inflated prices of the Gold Country.

By now this diverse group of lawbreakers had begun to assume a single identity—Joaquin Murieta. Love and his compatriots rode out to seize the cunning Joaquin and his reported accomplice, Three Fingered Jack. Three Fingered Jack was the alias of Manuel Garcia, who was wanted throughout California for theft and murder. On top of the threat to the general populace, it was noted that Garcia hated the Chinese and was a suspected serial killer of Chinese miners in Calaveras County. It was claimed that Joaquin Murieta had killed as many as 200 Chinese as well. In this tense atmosphere, the pressure to deliver Joaquin weighed heavily upon Love’s crew.

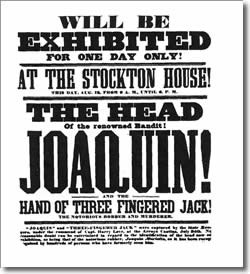

Three Fingers' Hand and Joaquin's Head?

For several weeks, they had no luck. Then ... near Panoche Pass, outside of Hornitos in the Southern Gold Country, Love’s patrol encountered a Mexican band. At least two of the Latinos were killed. One had claimed to be the group’s leader, but he did not mention his name. Love decapitated this supposed chieftain and had his head sealed in a jar of alcohol. Additionally, a hand was severed from a second victim and placed in a separate jar. Love claimed the head was that of Joaquin Murieta and the hand had once belonged to Three Fingered Jack. He returned triumphantly to reclaim his reward. Others were skeptical to say the least. A surviving member of the Mexican party stated that the head was clearly that of Joaquin Valenzuela. Witnesses who saw the gruesome pickled head swore that it bore no resemblance to the “actual” Joaquin. Love insisted that the grotesque relics were authentic. He exhibited them throughout the Gold Country for a $1 admission fee. Interestingly, Harry Love never displayed his grisly trophies in Calaveras County where the “real” Joaquin Murieta reportedly had a primary hangout.

For several weeks, they had no luck. Then ... near Panoche Pass, outside of Hornitos in the Southern Gold Country, Love’s patrol encountered a Mexican band. At least two of the Latinos were killed. One had claimed to be the group’s leader, but he did not mention his name. Love decapitated this supposed chieftain and had his head sealed in a jar of alcohol. Additionally, a hand was severed from a second victim and placed in a separate jar. Love claimed the head was that of Joaquin Murieta and the hand had once belonged to Three Fingered Jack. He returned triumphantly to reclaim his reward. Others were skeptical to say the least. A surviving member of the Mexican party stated that the head was clearly that of Joaquin Valenzuela. Witnesses who saw the gruesome pickled head swore that it bore no resemblance to the “actual” Joaquin. Love insisted that the grotesque relics were authentic. He exhibited them throughout the Gold Country for a $1 admission fee. Interestingly, Harry Love never displayed his grisly trophies in Calaveras County where the “real” Joaquin Murieta reportedly had a primary hangout.

Initially the show drew large crowds, but, by 1856, interest was dwindling. In that year, a San Francisco entrepreneur purchased the head and hand. They became permanent attractions in that city’s Pacific Museum. The items were said to have vanished in the aftermath of the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire.

Joaquin's Legend Grows Through John Rollin Ridge

While Love and his macabre carnival traveled the countryside, the legend of Joaquin Murieta grew.

In 1854, as recounted in the first part of this two-part series, a struggling gold miner turned writer named John Rollin Ridge (also known by his Cherokee name Yellow Bird) collected the various Joaquin stories and fused them into a single myth. From Ridge’s fertile imagination sprung a book entitled The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta, The Celebrated California Bandit. Ridge consolidated the stories, exaggerated actual details, invented breathtaking situations, concocted wild escapes, and promoted the image of Joaquin as a Mother Lode Robin Hood driven to crime by social injustice. The book is considered to be the first novel written by a Native American and the first novel published in California. Ridge’s introductory passage presented Joaquin’s persona and set the stage for the adventures that followed.

The first that we hear of him in the Golden State is that, in the spring of 1850, he is engaged in the honest occupation of a miner in the Stanislaus placers, then reckoned among the richest portions of the mines. He was then eighteen years of age, a little over the medium height, slenderly but gracefully built, and active as a young tiger. His complexion was neither very dark or very light, but clear and brilliant, and his countenance is pronounced to have been, at that time, exceedingly handsome and attractive. His large black eyes, mouth, his well-shaped head from which the long, glossy, black hair hung down over his shoulders, his silvery voice full of generous utterance, and the frank and cordial bearing which distinguished him made him beloved by all with whom he came in contact.

A longer passage is presented separately in this article – click here.

Ridge's Tale - Fact or Fiction?

Ridge exploited common knowledge of Love’s pursuit and cleverly ended his tale with the criminal genius captured and decapitated by the relentless Texas Ranger. When issued the account was considered comprehensive. The public knew that Love had killed a Mexican, most likely a bandit, so the assumption was made that the preceding passages had to be true. To this day, Ridge’s story is viewed as accurate by some and a few history books still cite Ridge’s fabrications as fact.

Grass Valley resident John Rollin Ridge died at age 40 in 1867, having realized little financial gain from his fable. But others profited. Contemporary artists, most notably the prominent Gold Rush artist Charles Nahl, painted fictionalized “portraits” of Joaquin Murieta which were widely disseminated and sold well. In 1919, the famous silent movie director D.W. Griffith made his only western—“Scarlet Days”—based upon the Joaquin Murieta legend. The film has been lost, although a handful of stills remain. Griffith passed on a young actor touted as being the perfect Joaquin—Rudolph Valentino. In 1932, Walter Noble Burns published The Robin Hood of El Dorado, a collection of Joaquin stories. In 1936, another Joaquin Murieta movie biography was produced starring Warner Baxter of Cisco Kid fame. Most folklorists believe the Zorro stories, popularized by author Johnston McCulley in his 1919 novel The Curse of Capistrano, are based, at least in significant part, on the Joaquin Murieta mythology. The combination of Ridge’s catalyst linked with these later creative endeavors solidified the position of Joaquin Murieta as a California historical and cultural icon. Zorro continues to be a popular cultural icon with movies and TV series produced to this day.

Love's Life Ends

One who did not profit significantly was Harry Love. Following the sale of his dismembered objects, Love operated a sawmill in the Santa Cruz Mountains. In 1858, he married but the relationship was bitter and argumentative and the couple separated soon afterward. In 1868, Love accused another man of having an affair with his estranged wife. The two men exchanged gunfire and Love was fatally wounded. He died on the operating table.

While having origin in the oppression of Gold Rush Latinos, the story of Joaquin Murieta is myth, speculation, conjecture, and fabulous adventure. It is not history, but legend. But it is entertaining legend that reflects historical actualities, romantic visions, and cultural exasperation. As long as there are those who remember the past, dream of adventure, or hope for the end of discrimination, it can truly be said that “Joaquin was here.”

And the myth’s beginnings were in the agile mind and prolific pen of the author known as Yellow Bird—John Rollin Ridge of Grass Valley.

The Poems of John Rollin Ridge

If you would like to read Ridge's poems, they are available online from the Sequoyah Research Center/American Native Press Archives.