“Streets of the Mountains”

by Mary Austin

from The Land of Little Rain, 1903

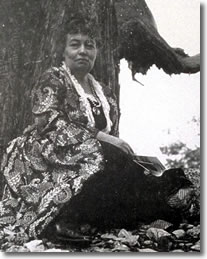

Mary Hunter Austin was an American writer of fiction and non-fiction who focused on the Sierra Nevada and Mojave Desert.

Mary Hunter Austin was an American writer of fiction and non-fiction who focused on the Sierra Nevada and Mojave Desert.

Mary Hunter was born in Carlinville, Illinois, in 1868. Her family moved to California in 1888 and established a homestead in the San Joaquin Valley. Mary married Stafford Wallace Austin in 1891. Their home in Inyo County, now a historical landmark, was designed and built by the couple. In addition to her descriptive writings on the region, Mary Austin became an expert on the Native American cultures of the southern Sierra and Mojave Desert and her studies became a respected addition to the ethnographic literature.

The Austins were involved in a contentious and sometime violent local water dispute, where the water of Owens Valley was eventually drained to supply Los Angeles. When their battle was lost, he moved to Death Valley and she moved to Carmel on Monterey Bay where she was part of a social circle that included Jack London and Ambrose Bierce.

In 1903, Mary Austin published The Land of Little Rain, her examination of the Owens Valley and the southern Sierra Nevada region. A 1950 edition of The Land of Little Rain featured photographs by Ansel Adams. In 1999, the San Francisco Chronicle Book Review polled its readers to choose the 20th century’s best 100 nonfiction books in English on the American West – from the Rockies to the Pacific. Outpolling books by such literary icons as Wallce Stegner, Edward Abbey, Ivan Doig, Bernard DeVoto, Joan Didion, Norman MacLean, Dee Brown, John Steinbeck, Gary Snyder, Ursula LeGuin, Tom Wolfe, Ambrose Bierce, Richard Rodriguez, Henry Miller, Jack London, and Norman Mailer, Austin’s Land of Little Rain topped the Chroncile’s Western 100 list. This was a remarkable tribute to a book published 96 years earlier about a region – the eastern Sierra Nevada—which the vast majority of Californians have never seen or visited.

In this passage, Austin describes the river canyons of the region, or what she called,

“The Streets of the Mountains.”

All streets of the mountains lead to the citadel; steep or slow they go up to the core of the hills. Any trail that goes otherwhere must dip and cross, sidle and take chances. Rifts of the hills open into each other, and the high meadows are often wide enough to be called valleys by courtesy; but one keeps this distinction in mind,—valleys are the sunken places of the earth, cañons are scored out by the glacier ploughs of God. They have a better name in the Rockies for these hill-fenced open glades of pleasantness; they call them parks. Here and there in the hill country one comes upon blind gullies fronted by high stony barriers. These head also for the heart of the mountains; their distinction is that they never get anywhere.

All streets of the mountains lead to the citadel; steep or slow they go up to the core of the hills. Any trail that goes otherwhere must dip and cross, sidle and take chances. Rifts of the hills open into each other, and the high meadows are often wide enough to be called valleys by courtesy; but one keeps this distinction in mind,—valleys are the sunken places of the earth, cañons are scored out by the glacier ploughs of God. They have a better name in the Rockies for these hill-fenced open glades of pleasantness; they call them parks. Here and there in the hill country one comes upon blind gullies fronted by high stony barriers. These head also for the heart of the mountains; their distinction is that they never get anywhere.

All mountain streets have streams to thread them, or deep grooves where a stream might run. You would do well to avoid that range uncomforted by singing floods. You will find it forsaken of most things but beauty and madness and death and God. Many such lie east and north away from the mid Sierras, and quicken the imagination with the sense of purposes not revealed, but the ordinary traveler brings nothing away from them but an intolerable thirst.

Names With a History

The river cañons of the Sierras of the Snows are better worth while than most Broadways, though the choice of them is like the choice of streets, not very well determined by their names. There is always an amount of local history to be read in the names of mountain highways where one touches the successive waves of occupation or discovery, as in the old villages where the neighborhoods are not built but grow. Here you have the Spanish Californian in Cero Gordo and piñon; Symmes and Shepherd, pioneers both; Tunawai, probably Shoshone; Oak Creek, Kearsarge,—easy to fix the date of that christening,—Tinpah, Paiute that; Mist Canon and Paddy Jack's. The streets of the west Sierras sloping toward the San Joaquin are long and winding, but from the east, my country, a day's ride carries one to the lake regions. The next day reaches the passes of the high divide, but whether one gets passage depends a little on how many have gone that road before, and much on one's own powers. The passes are steep and windy ridges, though not the highest. By two and three thousand feet the snow-caps overtop them. It is even possible to wind through the Sierras without having passed above timber-line, but one misses a great exhilaration.

The river cañons of the Sierras of the Snows are better worth while than most Broadways, though the choice of them is like the choice of streets, not very well determined by their names. There is always an amount of local history to be read in the names of mountain highways where one touches the successive waves of occupation or discovery, as in the old villages where the neighborhoods are not built but grow. Here you have the Spanish Californian in Cero Gordo and piñon; Symmes and Shepherd, pioneers both; Tunawai, probably Shoshone; Oak Creek, Kearsarge,—easy to fix the date of that christening,—Tinpah, Paiute that; Mist Canon and Paddy Jack's. The streets of the west Sierras sloping toward the San Joaquin are long and winding, but from the east, my country, a day's ride carries one to the lake regions. The next day reaches the passes of the high divide, but whether one gets passage depends a little on how many have gone that road before, and much on one's own powers. The passes are steep and windy ridges, though not the highest. By two and three thousand feet the snow-caps overtop them. It is even possible to wind through the Sierras without having passed above timber-line, but one misses a great exhilaration.

The shape of a new mountain is roughly pyramidal, running out into long shark-finned ridges that interfere and merge into other thunder-splintered sierras. You get the saw-tooth effect from a distance, but the near-by granite bulk glitters with the terrible keen polish of old glacial ages. I say terrible; so it seems. When those glossy domes swim into the alpenglow, wet after rain, you conceive how long and imperturbable are the purposes of God.