Communicating Science: This Is a Job For Superman!

by Randy Olson

Author, "Don't Be Such a Scientist"

So there I was last spring, giving my usual "Don't Be Such a Scientist" talk – basically presenting the contents of my book – to about two hundred faculty and students at a prominent east coast university. The Q&A started with a faculty member who stood up, turned to the audience and unleashed an almost-embarrassing flood of compliments about my book (notice I say "almost" – takes a lot for me). He went on and on about how he read it twice and how it was so great because I used stories and humor and emotion to make my point about the need to use stories and humor and emotion to communicate effectively with the general public. I sat there glowing, soaking in the praise, thinking, "Isn't this just wonderful!" Not knowing it was all a set up.

So there I was last spring, giving my usual "Don't Be Such a Scientist" talk – basically presenting the contents of my book – to about two hundred faculty and students at a prominent east coast university. The Q&A started with a faculty member who stood up, turned to the audience and unleashed an almost-embarrassing flood of compliments about my book (notice I say "almost" – takes a lot for me). He went on and on about how he read it twice and how it was so great because I used stories and humor and emotion to make my point about the need to use stories and humor and emotion to communicate effectively with the general public. I sat there glowing, soaking in the praise, thinking, "Isn't this just wonderful!" Not knowing it was all a set up.

He ended his speech, then turned to me with a critical glare and let me have it as he said, "But despite my love for your book ... I now have to tell you that your presentation here today was an enormous disappointment." Everything sort of went silent as I cleared my throat and looked back at him with an expression of, "um ... excuse me?" He went on to say, "I came here today expecting you to tell stories that would be filled with humor and emotion, but instead, all we got was ... boring."

Guess what. He was right. Of course I didn't say so at the moment. I instinctively coughed up a bunch of lame excuses about how it was an academic audience – had it been the general public I would have told stories and would have ... blah, blah, blah. But really there was no excuse. It was a hastily thrown together talk and I knew it. He caught me, red handed, and I said as much to him later at the reception.

"How dare you confront me with the truth in public!" I told him. He was sooo right. And I owe him an enormous debt of gratitude for jolting me out of my lazy post-book publication stupor.

Which brings me to the focus of this essay – the simple question of ...

Who Will Bear the Burden of Mass Communication?

This is where communicating with the public starts – with a simple fork in the road over who's gonna do the work. Are you willing to take a VERY large amount of time in figuring out how to present your information to the public in a way that they will "get it"? Or are you preferring to just dump everything out there like a yard sale and say, "Y'all just take whatever you want!"? That's the fundamental divide. And guess which strategy most scientists opt for.

To dig deeper into this, let's begin with an exercise.

Okay, tell me with a single statement what it is that you study. Without hesitation, you'll say something like, "I study the role of reproductive isolating mechanisms in speciation of California lizards." Okay. Great.

Now tell me the same thing in the form of a question.

And now you're hesitating. You're saying, "Um ... what? in a question? well ... let's see ... what do the ... no, how can ... wait, um ..." And then you finally say, "Okay, are reproductive isolating mechanisms important in the speciation of California lizards?"

There you have it. The central divide in mass communication. If you give me your information in the form of just statements, it's very quick and easy for you, but you are putting the burden of communication on me. When I hear a statement I have to ask myself whether it is interesting, whether I'm interested in it, and how does it relate to something in my world. That's a lot of work, and most likely I won't feel like exerting so much effort, especially given how overloaded my brain is with information these days. I just don't need more facts.

In contrast, putting it into the form of a question took a lot more time and effort on your part, but when you told it to me, we were only halfway done with our communication exercise. I heard the question, and even though I'm not interested in California lizards, I really, really hate for questions to go unanswered, so I wanted to hear the answer. Which is ... what? Come on, ARE they important or not? I really don't want you to leave until you've given me an answer!

This is the same dynamic that my local Los Angeles TV weatherman, Dallas Raines, puts to use every evening with his weather report. He begins with a dopey trivia question for which I honestly could not care a less about the answer, and I know full well that knowing the answer will have absolutely no bearing on the outcome of my life. And yet ... dammit ... I can NOT change the channel until Dallas has answered the dumb trivia question, and I've found out whether the largest glacier in the world is in Antarctica or Asia (btw, you'll get the answer at the end of this essay).

Arouse and Fulfill

The simple principle behind all this can be summed up with two words: AROUSE and FULFILL. I learned this twelve years ago when I interviewed USC Communications Professor Tom Hollihan. As he says, mass communication is relatively simple – first you have to arouse the interests of your audience, then you need to fulfill their expectations. If you haven't aroused them, they aren't going to listen to what you have to say. If you don't fulfill them they will feel like your arousal efforts were a waste of time.

Questions, as I was saying, are a form of arousal. If someone asks "a good question," everyone's interests get aroused. That's how it works.

In my two careers as a scientist and a filmmaker I've gotten to see the two ends of this spectrum. The people in Hollywood are incredibly good at arousal – they make films that will keep you up late at night. But they often have a hard time understanding the substance of issues. In my mockumentary feature film, "Sizzle: A Global Warming Comedy," one of the flaky Hollywood producers says to me, "We're really, really upset and worried about global warming but our problem is ... we don't know why we're so upset." That's kind of it in a nutshell. Lots of sizzle, not much steak.

At the other end of the spectrum are scientists. They are terrible at arousal. Now, I'm not talking about sexual arousal. Necessarily. (though I could) I'm talking about bothering to do the things necessary to arouse people's interests in what they have to say.

There's a tendency for scientists to simply feel that science by itself is so blindlingly, mesmerisingly, stunningly, amazingly awesome that it is automatically arousing. And of course, if that's your orientation, then you can see why a scientist would just jump right in with a whole bunch of facts. And that's exactly what I got to see last spring when we had scientists send us their videos for a science meeting ...

The "Here's What We Do" Science Film Festival

Last spring we ran an event at the Ocean Sciences Meeting in Portland, Oregon where we encouraged scientists to send in their 5 minute or less videos for presentation and critiquing. It turned out great. We got about 25 submissions, then chose 9 to present. Each video got 15 minutes where we would show the video, then I would offer up my constructive critique on what things could be different (we encouraged them to send in "works in progress" so they could incorporate some of the feedback), then let the audience ask questions.

Other than one wildman in the audience who ripped one video to shreds with his comments, the entire event was very constructive and helpful for everyone (and the wildman turned out to be friends with the filmmaker so it was okay – they were used to each other). But one clear pattern emerged from the videos that were submitted – none of them told stories. And what I mean by that is that none of them really asked questions. They were all just conglomerations of statements.

The typical video was a presentation of a research laboratory in which the video basically said, "Here's our lab, here's our scientists, here's their equipment, here's them in the field, here's the papers they've published, won't you come visit us some day!"

They were nice, but think back to my question about bearing the burden of mass communication. It was clear that very little thought went into, "How are we going to make this stuff interesting to people who aren't interested?" The videos just started with the assumption that you're dying to know what goes on at the lab. But the truth is, most people aren't.

And this is where Superman comes in.

You Gotta Tell a Story

What these folks were doing, and what I did last spring, is to present a whole bunch of "exposition." That's what statements are. And it's what good stories BEGIN with. But it's not a good story by itself.

If you watch a good murder mystery, how does it begin? It starts with a bunch of statements about a little town, a little old lady, a little house in the town, a little boy who lives next door, a washing machine repairman who comes to fix the lady's washing machine ... and then ... his body is found by the little boy out in the alley. Who dunnit? That's the beginning of a good story.

The problem with those science lab films and my talk is that they never even got to the point of the washing machine repairman showing up. They never told a story. They were just all those initial statements.

Imagine if that movie had gone from introducing the little boy to introducing his dog to showing the school he goes to showing the gas station down the road to showing the nearby river to ... After a while you'd start to say, "where's this all going?"

That's what happens with a lot of the general public when you make a video about your lab that just goes on and on with one statement after another. Eventually most people are saying to themselves, "Where is this all going, and why should I care?"

Which was the deal with my talk. I presented the contents of my book, but if you weren't really keen on what's in the book, then you eventually ended up thinking that same thing. But it didn't have to be that way. And I knew it, right when that guy said it.

Superman To the Rescue

So you know what I did – I set to work on a story. I spent the spring crafting a simple story that I could tell instead of that boring talk. And it was a story built around a question – the question of, "How do you get the public interested in what's going on at your lab?"

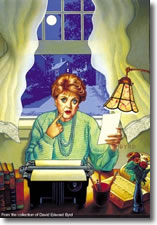

Working with a screenwriter friend of mine we came up with the STORY of a woman who is hired to be the new Communications Director of a fictitious laboratory on the coast of Maine. She sets to work trying to get the general public more interested in the lab. To do this she films a documentary about what goes on at the lab. But similar to the videos I described, what she ends up with is a bunch of statements that don't tell much of a story and by themselves are pretty boring.

She shows the video to a number of key people, they all say it's just boring, and she ends up frustrated and depressed. She goes to her favorite coffee shop to get her mind off things, but ends up meeting a good looking local fisherman. They begin chatting and he tells her about the history of the laboratory – there are actually great stories of major accomplishments of the lab in the past. He offers to take her out on the bay in his boat sometime. She thinks he's pretty cute.

And then that night she falls asleep watching her boring documentary, but is awoken in the night by a noise. She looks over and there, on the other side of her living room, of course, is Superman (who bears a striking resemblance to the fisherman).

Superman proceeds to tell her the basic contents of my book. She wakes up the next morning, is inspired to reshoot her documentary following Superman's advice, and takes the fisherman up on his boat ride offer which turns into a long and happy romance. End of story.

That's now my talk. Last month I pulled together 5 actors who posed for the various scenes as we shot photos that are now about 50 slides in my talk. I've given it twice. Does it work? Who knows. I can only say that nobody has called it disappointing or boring so far, and the love story gets HUGE laughs.

More importantly, the first run I did of it with friends showed one clear pattern – the main thing EVERYONE enjoyed and remembered most clearly was the love story. Which tells us volumes about the basic principles of arouse and fulfill.

End of Story

So that's your basic principle for communicating with the general public. They want you to tell a story. But more importantly, for you to even be ABLE to tell a story, you HAVE to know what a story is. It's not a collection of statements. It begins with a question. That's the point where the audience joins with you in the thought process – that's where they begin saying, "Yeah, who DID kill this person?" And that's when you've got them.

And no, you don't have to have a dead body. I don't have one in my talk (... yet!). Just getting to know this woman who takes the job, then is frustrated with the communications challenge is enough to engage the audience as we set up the question of, "HOW is she going to succeed at reaching her audience???" It's that simple.

And once you've hooked them with the question, almost everyone will stick around, even if it's just to find out what the answer is to the question.

Okay. Now to finish. The answer to the trivia question can be found by counting the number of paragraphs in the first section of this essay. If it's five then it's Antarctica. If it's eight then it's Asia. But most importantly, if you find yourself counting the number of paragraphs, then you have to concede that the question/answer thing works. Indeed, it really is how you arouse and fulfill your audience.

You can read more about communicating science from Randy Olson at his blog at http://thebenshi.com or in his book “Don’t Be Such a Scientist”.